A Russian motorist near Ryazan (southeast of Moscow) recorded a video earlier this year of an unusually large, low-flying drone with a V-shaped tail and wings spanning a whopping 23 meters from tip to tip.

This was a rare sighting of a “heavy attack” drone that was developed by Russian drone-maker Kronshtadt prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It’s called the Sirius, named after the brightest start in the sky. Sirius was intended as a higher-performance, twin-engine successor to the single-engine the Orion UCAV, which saw combat use earlier during the invasion.

Samuel Bendett, an expert on Russian uncrewed systems and AI at the Center for Naval Analyses and the CNAS think tank, wrote to Pop Mech:

“Sirius is a pre-war legacy system, along with Helios long-range ISR drone and other Kronstadt projects. This is supposed to be one of the flagship projects to propel Russia into the rank of drone superpowers on the air with the US, Israel and China. Sirius is supposed to be a significant upgrade of Orion in practically all capabilities.”

Russia’s first missile-armed combat drone to enter service, the Inkhodets (“Orion”) medium-altitude long endurance (MALE) drone began production in 2021, just a year before Putin launched his invasion of Ukraine. That’s somewhat shocking, given that the U.S. began using large combat drones (or UCAVs) two decades earlier in Afghanistan. Russia’s long lack of similar capability allowed China, Israel, Turkey, and even Iran to capture most of the killer drone market for years, at least with regards to countries without access to U.S. exports.

However, following embarrassing military setbacks during Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, Moscow purchased drone technology from Israel, giving domestic firms the tech injection needed to develop and finally combat test Orion UCAV and KYB kamikaze drone prototypes over Syria in 2018. Those trials, in turn, allowed Russia the operational drone capabilities with which it began the war in Ukraine.

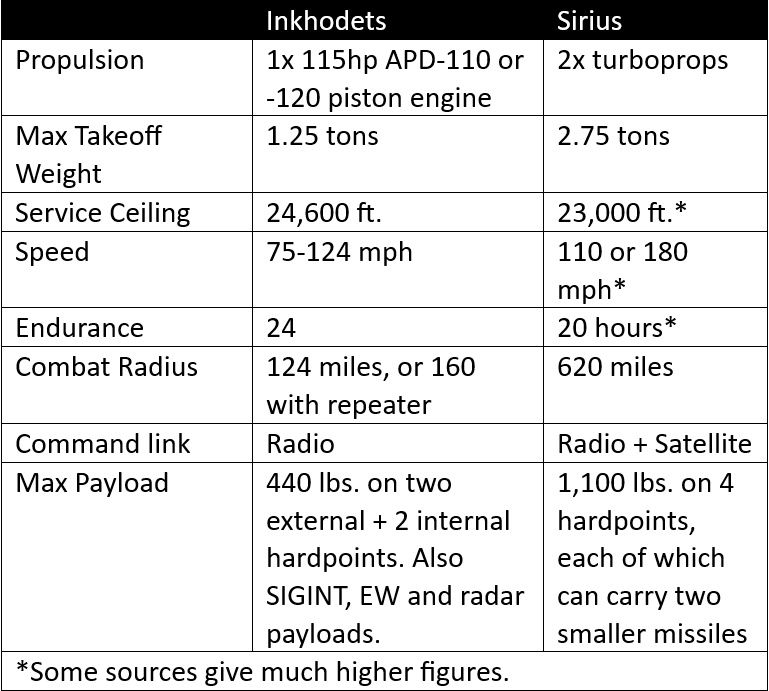

But waiting in the wings (and with bigger wings) were many new UCAV designs at various stages of development. One of them, Helios (or Orion-2) was for a higher altitude (HALE) drone. Meanwhile, Kronshtadt’s Sirius—also sometimes dubbed the Inkhodets-RU—was basically a twin-engine variant of the Orion: still a MALE drone, but with greatly improved performance.

A mockup of Sirius was displayed at the 2019 MAKS airshow, while construction of a flying prototype began November of 2021. While originally planned to enter service in 2023, it instead made its first flight on February 27, according to a leaked Pentagon report.

Key changes include much greater range, and support for a satellite communications (SATCOM) antenna that will allow for remote control over huge distances.

It also can carry heavier, harder-hitting bombs and missiles ordinarily reserved for manned warplanes. That supposedly includes 1,100-pound class RBK-500U cluster bomblet dispensers and destructive ODAB-500PMV fuel air explosives. The drone also benefits from a ground-mapping Synthetic Aperture Radar that can help generate terrain maps, as well locate ground-vehicle and artillery targets.

Sirius will supposedly come in three variants—one for attack, one for reconnaissance only, and one for maritime patrol. The last submodel, operated by Russia’s navy, is intended to have payloads for anti-submarine ops, search-and-rescue, maritime reconnaissance, and signal-repeater duties. Production will begin at a facility in Dubna (55 miles north of Moscow).

Russia’s war has drained away much R&D funding, but according to Bendett, service entry may not be that distant now. “At the moment,” he said, “work is ongoing given all the resources invested on this project which is also supposed to be mostly domestically sourced. As far as public resources go, Russia is on track to start mass production sometime this year.”

Asked if Sirius was likely to come standard with satellite communication antennas, Bendett said that he believed it was “likely, but unclear to what extent.”

However, others are skeptical that Russia’s GLONASS navigational satellites are in sufficiently good state for Russia to depend on them for long-range drone flights. Though, it is worth bearing in mind that the drone may still access GPS or other satellite-navigation systems instead.

Useful Over Ukraine?

Early in the war, a spate of videos showed missile strikes by Orion UCAVs, which can be used to confirm the destruction of five trucks, a couple towed howitzers, and three tanks. Forepost-R drones—a modification of a reverse-engineered Israeli reconnaissance drone—claimed six more vehicles.

Clearly, then, Russia’s UCAVs achieved some results, but on a vastly more limited scale than the killing sprees of Bayraktars drones over Libya, Syria and Nagorno-Karabakh. By contrast, there are many more successful attacks recorded on video of Russia’s Lancet kamikaze drones.

Furthermore, footage of Orion strikes petered out almost entirely after the Fall of 2022.

Experts are pretty sure they know why. In the war’s first weeks, both sides’ ground-based air defense coverage was spotty, giving UCAV drones a window of viability. But once ground-based air defense coverage was fully active, neither side’s UCAVs had acceptable survivable odds.

A May report penned by Bendett on Russian uncrewed systems by the Center of Naval Analysis concluded:

“…although [Orion] worked well for the Russian military against antigovernment forces in Syria, they are not equipped with robust defenses, making them vulnerable to Ukraine’s counter-drone and air defense systems. After some initial combat sorties, the Forpost-R and Orion drones now seem confined to ISR missions because of their initial low numbers and concerns over further UAV losses if used on attack missions, according to a Russian MOD broadcast.”

Essentially, while medium-altitude combat drones can safely attack insurgents or poorer armies from outside the range of their flak guns and portable anti-air missiles, a wealthier, state-level opponent fielding many medium- and high-altitude air defense systems—such as the Buk, the S-300, and even fighter planes or shorter-range defenses like the 9K33 Osa—can still easily engage slow-moving, high-flying MALE drones.

And costing multiple millions of dollars each, UCAVs are too valuable at to treat as being entirely expendable. By June 2, 2023 photos have confirmed that Ukraine has lost at least 19 Bayraktars, while Russia has lost four Orions and several additional UCAV types.

While Sirius improves on the Orion with greater range and payload capacity, it seems likely to run into the same survivability problems limiting use of other UCAVs over Ukraine.

Still, Sirius may provide Russia some additional capabilities at a standoff distance, whether for reconnaissance/surveillance or for serving as a launch platform for heavier, longer-range weapons. It could also be used for rear-area security in areas removed from Ukrainian air defense coverage, or provide ISR capabilities in conjunction with strikes by Russian fighters.

“Other functions may indeed be considered like maritime capacity or a drone carrier platform, but its real usefulness can only be confirmed once it’s operational,” Bendett wrote.

Scourge Over the Black Sea?

One arena where Sirius’s expanded range and weapon’s payload capability seem most applicable is over the Black Sea, where ground-based air defenses will be a smaller factor—especially as Ukraine’s Navy lacks warships with high-altitude air defenses.

The viability of UCAVs in this environment was demonstrated last Spring, when Ukraine's Bayraktar drones managed to devastate Russia’s Snake Island garrison (and the boats dispatched to relieve it) until the survivors were forced to evacuate.

Russia might, therefore, attempt to use Sirius for maritime domain awareness over the Black Sea—perhaps most importantly attempting to detect and potentially destroy Ukraine’s uncrewed kamikaze boats harrying Crimea, as well as hunting its manned patrol boats. Further afield, it could monitor Ukrainian commercial shipping activities, or shadow NATO ships in the Baltic or Sea of Japan.

Such maritime ops, though potentially useful, would remain a sideshow to Russia’s bigger military challenges in Ukraine, which the Sirius probably can do little to change.

Sébastien Roblin has written on the technical, historical, and political aspects of international security and conflict for publications including 19FortyFive, The National Interest, MSNBC, Forbes.com, Inside Unmanned Systems and War is Boring. He holds a Master’s degree from Georgetown University and served with the Peace Corps in China. You can follow his articles on Twitter.