Michaelmas, the feast of Saint Michael, has just been and gone. You probably didn’t notice. Saint Michael’s popularity and influence seems to have waned a little over the centuries, but he was once a major figure, with various feast days dotted around the year. Actually, he isn’t really a saint. He isn’t even a he. Michael is of course an Archangel, a heavenly warrior and protector of humans from evil and the devil, a psychopomp, and holder of the scales upon which the souls of the dead are weighed. You might ask yourself how it is that a supernatural being has a feast day at all, when generally feast days are said to mark the day upon which a particular saint travelled to the next world. The question isn’t merely of religious interest. I happened to stumble on something that is curiously pertinent to anyone interested in megalithic cultures, and the great cathedrals. It all begins with the Michael Apollo alignment.

This axis is an intriguing collection of places, some Stone Age, some Medieval, dedicated to the Archangel Michael, to Apollo or to Artemis. I decided to have a closer look at it when I discovered that, to my great surprise, two of the most important sites on this alignment were exactly the same distance from Stonehenge. What I found was an incredibly precise network of sacred places across north west Europe controlled by Phi, the golden number, and Michaelmas, and the cycles of the sun and the moon.

The Michael Apollo Artemis Alignment

Perhaps the Michael Apollo Artemis line - I prefer to include Artemis in the name too - is just a curiosity. From the western edge of Ireland to the eastern edge of the Mediterranean, a handful of sacred places plot the remains of an ancient path: the western side is Michael's, the eastern belongs to Apollo and Artemis. Ancient alignments hold no great sway with most historians, and this one even less so because, as alignments go, it's not particularly straight: on a map, many of the places supposedly on it are a good few miles off course. What's more, seen on Google Earth, the line is markedly curved, like a broad smile. Perhaps it’s the gods chuckling. If you were to draw a straight line between its western and eastern tips, none of the places on this alignment would be included. Also, it's impossibly long, like a crazy pencil skid across the globe. Were it intentional, how could engineers and surveyors of the distant past, with all the technological shortcomings we like to ascribe to them, possibly have brought it about? There’s an English Michael line too: it is said to stretch from Land’s End in Cornwall, right through the south of England, to Norfolk. There’s also a short Norman Michael line in France, from Mont-Dol to Avranches. So how can we make sense of these Michael lines?

The research that has been done on this supposed axis has been mostly outside academia. Katherine Maltwood alludes to the English line in her Guide to Glastonbury's Temple of the Stars (1935), which is picked up by John Michell in his View Over Atlantis in 1969. A few years earlier, in 1966, Jean Richer publishes his Géographie Sacrée du Monde Grec, which examines alignments between sacred Greek places, and in 1977 his brother Julien writes that an alignment through the Greeek islands can be extended all the way to the Mont Saint-Michel and beyond, to Saint Michael’s Mount and Skellig Michael. More recently, Lucas Mandelbaum (The Axis of Mithras: Souls, Salvation, and Shrines Across Ancient Europe, 2016), and Yuri Leitch (The Terrestrial Alignments of Katherine Maltwood and Dion Fortune) have contributed immensely to the research. And yet, there is still so much that doesn’t quite make sense. What was the alignment for? How was it produced? How old is it? What do the places on it have in common? Is the Archangel Michael somehow connected to Apollo and Artemis, or to Mithras? How much of it was preserved and built on by the Christians, and how much destroyed? Does this alignment really exist as one single long line with a logic to it? It’s kind of like mercury, it’s hard to pick it up in one piece.

One of the main problems with this line is the constant change of bearing from place to place. In fact, the Michael Apollo line across Europe changes azimuth at every point. Skellig to Saint Michael's Mount is 115.42°, then Saint Michael's Mount to the Mont Saint-Michel is 118.33°, Mont Saint-Michel to Le Mans Cathedral (Place Saint-Michel) 118.21°, Le Mans to Sacra di San Michele 118.02°, Sacra di San Michele to Monte Sant'Angelo, 115.41°, Monte Sant'Angelo to Corfu, Artemis Temple, azimuth 123.7°, Corfu, Artemis Temple to Temple of Apollo at Delphi, 118.50°, Temple of Apollo at Delphi to Delos, Temple of Artemis, 115.52°, Delos to Archangelos, Rhodes, 116.6°, Rhodes to Mount Carmel, Stella Maris Monastery 119°. That's a significant change in bearing from point to point. What's more, the change is not gradual. And how to account for some of the places on the line being far apart, and others not? The more you look at this line, the less sense it makes.

There's not all that much to go on. In that respect, it's a little like the concept of dedicating a place to an Archangel, who leaves his devotees with no bones, skulls, or cloths to show off and attract pilgrims with. The whole thing is in fact quite postmodern, like playing tennis without a ball.

Saint Michael's Mount, Mont Saint-Michel and Skellig Michael

Actually, there is a skull. Housed in the basilica closest to the Mont Saint-Michel in the town of Avranches, it is the skull of a man touched by the finger of the Archangel, with a mysterious hole in its side, a hole that preceded it’s owner’s death, proof of Michael’s presence. It belonged to the Bishop of Avranches, the founder of the monastery on the mount who'd had a vision: the Archangel Michael instructed him personally to build a church on this spectacular piece of rock (which until then had simply been known as the Mont Tombe). It is an amazing place, a rock, jutting out from sands and sea, a tidal island completely built upon, and what buildings. The abbey and its surrounding structures are still known as 'La Merveille', the marvel, and considered to be one of the finest examples of medieval architecture in the world. A sister monastery was founded on a similar tidal rock just over 200 miles away, off the coast of Cornwall, in England. Or, as the Cornish might prefer, off the coast of Cornwall.

A third Michael rock in the sea, but a little further from any coast, is the majestic Skellig Michael, which soars out of the Atlantic towards the sky. It offers almost no horizontal piece of ground, and is impossible to land on except in fair weather. Despite the gales, the damp, the isolation, the lack of vegetation, somehow, a monastery was built there too. Skellig, like the other two Michael rocks, was a place of pilgrimage for many centuries, and still is today - mainly for Star Wars fans, as Luke Skywalker spent some time there. Together, Skellig Michael, Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel form the first part, and perhaps the most breathtaking part of the Michael Apollo Artemis axis. If a pilgrimage was intended between the three, it would have entailed at least three boat crossings and very limited and rough accommodation, so why link them by line and name? It’s not impossible that these three rocks might represent stars. The arrangement of the three points in an almost straight line is a little suggestive of Robert Bauval’s Orion correlation theory. Do the three points fit into the relative distances between the three stars of Orion’s belt? If you take the arrangement of the three pyramids at Giza as a guide, the distance between the larger two is 486.87736 m / 19,168.4 inches, and between the second and third 453.97928 m / 17,873.2 (distances from centre to centre, from William Flinders Petrie). Going to the Michael Mount alignment, if you take the value of the longer distance, that between Skellig Michael and Saint Michael’s Mount, which is of 248.83 miles, if the three rocks mirrored the arrangement of the pyramids at Giza, you would then expect a distance between Saint Michael’s Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel of 232.02 miles, but it is quite different, at 206.14 miles. That doesn’t really work. Perhaps another group of stars, maybe the Pleiades? Perhaps the Milky Way itself?

What do these places have in common? They are all tiny rocky islands which, on a map, form an almost straight line. On Google Earth, a line drawn between the Irish and Norman Michael rocks skirts the vicinity of Saint Michael’s Mount in Cornwall, about two miles to the north. For some reason, someone picked out these places long ago, out of all the many islands off the coasts of Ireland, Britain and France, to dedicate them to an Archangel, or perhaps another divine being in earlier times. None are easy places to live in, being regularly battered by the sea, most especially the Irish one. What does this triad of Michael rocks mean? According to Wikipedia, not much, it's all a coincidence. There are four other islands in Europe dedicated to Michael that I know of: one is off the coast of Brittany and is precisely the same distance from Stonehenge as are Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel; one is a tiny rock off the Isle of Man; the other is a Venetian island; and there is also an island in the Atlantic, in the Azores, almost 900 miles off the coast of Portugal, called São Miguel. There was once another, just off the south coast of Cornwall, whose name was then changed to the less French sounding St George, still keeping the theme of the dragon slaying protector, and has since changed again, to Looe. There is also a tiny island in the Lac de Serre-Ponçon, in the French Alps, with a chapel to Saint Michel on it. Is there any significance in three of the eight islands I know of in Europe with a connection to Saint Michael being aligned with each other, and three of these islands being the same distance from Stonehenge?

I am inclined to think that there is meaning in this, not only because half the islands in Europe named after Michael are aligned, but also because of their links to the most famous and enigmatic Stone Age site in Europe, and I think it’s the best place to start: Stonehenge.

Saint Michael's Mount, Mont Saint-Michel and Stonehenge

A few years ago, I downloaded Google Earth onto my laptop, and I amused myself by looking up places such as those mentioned already, that I had read about and was interested in. It was like learning the landscape in a whole new way, and I enjoyed traipsing up and down between places, over land and sea, measuring, comparing, and connecting. I noticed something that at first I didn't give much thought to. The Mont Saint-Michel and Saint Michael's Mount were exactly the same distance from another famous site, but with which they had absolutely no connection at all: Stonehenge. Not being able to explain this coincidence, I shrugged it off as just weird, as one might a deja-vu, or some supernatural experience. But the idea that two natural parts of the landscape should be positioned in such a way in relation to the most famous prehistoric monument in England kept nagging at me, and it seemed clear to me that the islands certainly hadn't been put there because of where Stonehenge was. Rather, Stonehenge may have been put there because of where these two islands were (amongst other possible reasons). And these islands weren't just two random islands, but had been specially selected by followers of a cult to the Archangel Michael - not that that linked them to Stonehenge, but at least it linked them to each other. But Stonehenge was Stone Age, and these islands had only early Christian and medieval connections, as far as anyone knew. And surely if there had been a link, there would be something about it online. But no, there was nothing.

Nothing, at least, that is, unless you count the legend of King Arthur. He was apparently involved in moving the stones that make up Stonehenge from County Kildare, across the Irish Sea and over to Salisbury Plain: his magician Merlin did it all, with strange incantations, and magic, and possibly the help of giants. And at the Mont Tombe, the old name for the Mont Saint-Michel, King Arthur tried but failed to save a young girl called Helen who'd been abducted by a terrible giant and taken there. After discovering her distraught grieving nurse, for he was too late to save the girl, Arthur had fought single handedly with the giant, and won. And of course there is a famous giant legend attached to Saint Michael's Mount too: Jack the Giant Killer. So King Arthur was linked to Stonehenge and the Mont Saint-Michel, and giants were slain on both the Michael Mounts.

As a child I liked stories about fighting and chivalry, and I still do, though I am more inclined to read Bernard Cornwell than stories about Lancelot and Gawain and the Green Knight now. And in my childhood we used to stop off at Stonehenge once a year or so, on the way to Devon to visit family, and in those days you didn’t need a ticket, you could just rock up and have a wander, and go right up to the stones. I always kept an interest in both medieval writing and art, and places like Stonehenge, so I was bemused to find both of these interests united with the mystery of the Michael Mounts. I’d read alot on the subject of how bright and technically savy our Stone Age ancestors were, with books such as Graham Hancock’s, Robert Bauvals’s, Robin Heath’s, John Michell’s, and alot of online material from researchers such as Anthony Murphy, David Warner Mathisen, and lectures from the Megalithomania series posted by Hugh Newman, amongst many others. I had also spent a lot of time trying to understand the many ramifications of Robin Heath's Lunation Triangle (The Lost Science of Measuring the Earth, co written with John Michell), which links Stonehenge, the island of Lundy and the Preseli Hills in Wales, where the blue stones at Stonehenge were originally quarried. For Robin Heath, the famous stone circle is linked to an island alright, but not to either of the Michael Mounts, only Lundy, an island I have often looked out to from the north coast of Devon. Still, I felt encouraged enough by the connection between Stonehenge and any island at all, to try and look further into it myself. I went back to my trusty Google Earth, and I found some amazing connections.

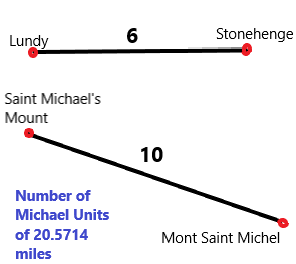

The first was this: the distance between Stonehenge and Lundy (24 x 36 / 7 miles) is precisely 7/10ths of the distance between Stonehenge and the Michael Mounts. And the distance between the two Michael Mounts is less than half a mile more than 10/6ths of the Stonehenge Lundy distance. Robin Heath has already convincingly shown that the distance between Stonehenge and Lundy is significant, partly because it is a nice round number of Astronomical Megalithic Yards, units derived from the cycles of the sun and moon, and partly because the whole triangle of which Lundy was a part was present on the ground at Stonehenge in the form of half the famous station stone rectangle. In fact, what he and John Michell showed, in The Lost Science of Measuring the Earth, is that at some point before 3,000 BCE, the inhabitants of the British Isles knew the dimensions of the Earth, had accurately surveyed at least parts of Britain and Ireland, used units of measurement derived from the cycles of the sun and the moon and the size of the Earth, and that the system they came up with was still in existence in the Middle Ages. So a connection between the distances linking Stonehenge with Lundy, and Stonehenge with the Michael Mounts now seemed very intriguing. It also made a connection between Neolithic places and Medieval places plausible, if the system was still in use in medieval times.

So here was this Stonehenge Michael Mount triangle, across hundreds of miles of land and sea, to try and make sense of. What was there to go on? It's size was linked to the Lunation Triangle discovered by Robin Heath. And it's proportions? An isosceles triangle, with sides of 6:6:7, and, what's more, a golden triangle (involving Phi). The distance between Stonehenge and the midpoint between the Mont Saint-Michel and Saint Michael's Mount is almost exactly the distance between Stonehenge and each of the Michael Mounts times Phi and divided by 2. Incredible. To make this golden triangle absolutely exact, you can place the top angle a mile and a quarter south west of the stone circle at Stonehenge, and then its absolutely perfect. And where there is a golden triangle there is potentially a pentagon. I did trace one onto Google Earth, but it's corners didn't seem to go through anything interesting apart from the Michael Mounts.

Skellig Michael, Mont Saint-Michel and Durham Cathedral

Then I began to wonder about the third Michael island, Skellig, and how it was linked to this golden triangle - I felt sure that it must be in some way, even though it's an awfully long way away. No other land is further west in Europe than Skellig Michael, apart from the Blaskets, a group of islands just north of Skellig, also off the coast of Kerry. Was this place part of a triangle too, or connected in some way to Stonehenge? Well, I spent a long time measuring this and that, and it turns out that Durham Cathedral is the key. Yes, Durham, in the North of England. This might sound quite improbable, but the Mont Saint-Michel and Skellig Michael are at exactly the same distance from Durham, so that Durham Cathedral, Skellig Michael and the Mont Saint-Michel form another isosceles triangle. It's not a golden triangle, but there is one strange detail about it: the two equal sides each measure the square of the distance between the Mont Saint-Michel and Saint Michaels' Mount divided by 100. Skellig Michael is the same distance from the Cornish Saint Michael’s Mount as Stonehenge is from Durham Cathedral, which is one hundredth part of the meridian circumference of the earth. Oh and there's another curious thing, a line traced from Durham Cathedral to Saint Michael's Mount goes straight through the centre of the island of Lundy, the western tip of Robin Heath's Lunation Triangle.

Some figures:

Saint Michael's Mount - Mont Saint-Michel : 206.14 , 118.33°

Skellig Michael - Mont Saint-Michel : 454.93 miles, 114.98°

Skellig Michael - Saint Michael’s Mount: 248.83 miles, 115.43°

Stonehenge - Durham Cathedral: 248.8 miles, 2.30°

Meridian circumference of the earth: ancient value: 24,883.2 miles according to Robin Heath, Wikipedia modern value: 24,901.461 miles

Durham Cathedral - Mont Saint-Michel: 424.30 miles, 179.60°

Skellig Michael - Durham Cathedral: 425.18 miles, 57.21°

Durham Cathedral- Lundy: 280 miles, 208.62°

Durham Cathedral - Saint Michael’s Mount: 361.56 miles, 208.62°

Stonehenge - Saint Michael's Mount: 176.43 miles, 246.75°

Stonehenge - Mont Saint-Michel: 176.32 miles, 175.32°

Stonehenge - Lundy: 123.44 miles, 271.08°

24 x 36 / 7 = 123.4286

24 x 36 / 7² x 10 = 176.3265

176.3265 x 7 / 6 = 205.71425

123.4286 x 10 / 6 = 205.7143

206.14² / 100 = 424.936996

The precision of the distance between the Mont Saint-Michel and Stonehenge especially, as 24 x 36 / 7² x 10 miles, and as precisely 10/7ths of the Stonehenge Lundy distance is, I think, astounding. The distance between the two Michael mounts is a little off ten sixths of 24 x 36 / 7 miles (205.7142 miles), being in fact 206.14 miles, but only by less than half a mile, and the two islands are, after all, natural features. In fact the distance between them is intriguingly close to the number of inches in the width of the King's Chamber of the Great Pyramid, 206.13, and the value of a cubit in inches. The position of Durham Cathedral in relation to the Mont Saint-Michel and Skellig Michael is also enigmatic.

Durham Cathedral is, as it happens, also built upon a mound and surrounded by water. But this mound seems to be a natural hill, it’s a good ten miles fom the coast, and the water than runs round its base is a meander of the river Wear, curled almost into the shape of an eye. There is another, perhaps more interesting alignment culminating at Durham Cathedral: almost perfectly due south is the Mont Saint-Michel, just 0.4 degrees off, and the line to it, from Durham Cathedral, goes right through the northernmost henge at Thornborough, a group of gigantic henges in Yorkshire made famous recently by a book called Before the Pyramids, in which the authors, Christopher Knight and Alan Butler compare the arrangement of these henges with the Giza pyramids, and with Robert Bauval's famous Orion correlation theory, whereby the pyramids are designed to represent exactly, here on earth, the three stars of Orion's belt.

My next question was then: how does all this tie in with the Archangel Michael? I read up about this enigmatic figure, a snake or dragon slayer, a protector and helper of humanity, together, the patron saint of several countries, two of which, ironically, had had for a long time an entrenched habit of war with each other. Was the cult of the Archangel Michael the legacy of some sun worship indigenous to northern Europe? There seem to have been two major phases of building churches and monasteries dedicated to the Archangel, the first being in the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries. The earliest known settlement at the Mont Saint-Michel was founded by an Irish hermit in the sixth century, and the Archangel Michael appeared in 708 to Aubert of Avranches instructing him to build a church there. The oldest shrine in Western Europe dedicated to the Archangel Michael is the Sanctuary of Monte Sant’Angelo on Monte Gargano in Apulia, in Italy, where in 490 the Archangel Michael appeared several times to the Bishop of Sipontum near a cave in the mountains, instructing that the cave be dedicated to Christian worship. A second important phase was in the 10th and 11th centuries, the time of the great cathedrals, when the Normans ruled large swathes of Europe, from Ireland to Sicily, and the time of the Crusades to the Holy Lands. In fact, the territories the Normans were interested in seem to coincide quite well with the European Michael axis, from southern Ireland to modern day Israel. But how to connect this archangel figure to the alignments?

In practical terms, all I really had to go on was the feast days.

So, how does a non-human entity have a feast day? Or, for that matter, several feast days? What exactly do the dates correspond to? My best guess was that the feast of an Archangel must mark an event in the sky. Actually, I couldn't think of any other explanation. The main feast of Saint Michael is on the 29th of September, Michaelmas, was once an important time of the year, by which date accounts were to be settled and blackberries eaten, less the devil pee on them and spoil them. This last bit of advice seems a little odd, if only because many of the blackberries where I live are still green, and I’m waiting to be able to pick them long after Michaelmas. But there are other feast days too, the 8th of May, the 6th of September, the 16th of October, the 8th of November, the third Sunday after Easter... This has to mean that the feast days of Michael were, by their very number, important in some way. The only other figure with several saint days that I could think of was the Virgin Mary, possibly the most important figure in Catholicism, after her son.

I thought it best to start with trying to figure out the movements of the sun as seen from Skellig Michael, and I found a great website called www.sunearthtools.com. You put in the location and the date that you want and you can get the number of hours of daylight and the orientation of the rising and setting sun, amongst other things.

Michaelmas

I wondered what date to pick first. I thought the most obvious would be to check the main feast of Saint Michael, the 29th September. The next thing to do was see what this sunrise azimuth corresponded to, so I drew a line accordingly on Google Earth from Skellig Michael.

I was very very surprised to find that it led straight to the Stonehenge area.

I just stared at the screen not knowing how to interpret this, dumbfounded. The first moments of Michaelmas sunrise at Skellig Michael, off the West coast of Ireland, were linked with Stonehenge, all the way over in England, almost four hundred miles away? For some reason, it just seemed unlikely. And yet, why not? It seems clear to me now that people in the distant past were good astronomers and cartographers, the capability was there. And the will was there, plenty of structures from the Neolithic and Bronze Age are oriented to something or other in the sky.

The line I traced didn't actually go through the main part of Stonehenge, the famous ring of stones, but just under a mile to the north, between the Great Cursus and Durrington Walls. I then went from wondering at the precision of this connection to wondering why the line between Skellig and Stonehenge wasn't more precise, why it didn't head for the henge itself. But then I figured that the sunrise azimuth for the days immediately before and after would have been way off the mark. If the intention of whoever designed this layout was to mark the Stonehenge - Skellig line exactly with this date, then actually the 29th September was the best you could do. The previous day, the 28th September and the following day are both way off - by several miles.

The sun does not appear as a minuscule point, but rather is fairly broad. One side of the sun could give a projected line with one azimuth, the other side a slightly different one, which, over distances of hundreds of miles, would result in one projected line being a mile or two more to the south or north than the other. But even if you were to take the very centre, or top centre of the disk as your guiding point, there is another reason why the azimuth given by the first moment of sunrise might not tally with the azimuth of a projected line from that place to a desired location exactly. As it rises, the sun moves not only upwards, but towards the south, and continues on its journey south all morning, as it rises. And there’s one other thing: as the year is really 365.25 days long, and our calendar only 365 days long, one 29th September sunrise azimuth will be a little different to the next, and so on. The azimuth I had been using was for sunrise in Skellig in September 2019 (92.69°), but a quick look at sunearthtools.com for the value for 2020 is slightly different again: next year it will be 93.17°, which would take you slightly south of the stone circle at Stonehenge. The azimuth from the centre of Skellig Michael to the centre of Stonehenge is 92.81°, which is just between the 2019 and 2020 Michaelmas sunrise values. To me, there is no doubt that Stonehenge was the target, quite literally, for anyone watching sunrise on the 29th September from Skellig.

Might the builders of Stonehenge have wanted to try to place their building project according to a sunrise azimuth which today corresponds to, from Skellig Michael, the 29th September, and why? Was it because it marked a stellar event, which survives to this day as Michaelmas sunrise from Skellig, and thus gives us the feast day of Saint Michael? In, say, 5,000 BCE, a sunrise azimuth with as close to a Skellig Stonehenge azimuth correlation as possible, would have taken place on the 7th of November, and in 6,000 BCE on the 14th of November. With 11 hours and 46 minutes of daylight for this last date, it would still have been only a few days apart from an equal day and night ratio, but more interestingly, the sun would have risen in Sagittarius, right in the head - was this significant in any way? By the time of the Normans, say 1066, the sun was rising in the head of Sagittarius around the 16th of December, and in the bow on about the 6th of December, so the Sagittarius connection would not have been possible. Now, in our epoch, the sun rises in Virgo this week, at Michaelmas. This was also the case in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when the Normans were building cathedrals dedicated to Mary all over their lands, such as Notre-Dame-de-Paris and Chartres.

Why was Skellig Michael important in the first place? It was an Irish monk who set up the earliest known settlement on the Mont Saint-Michel - was he connected to Skellig? Was he maintaining this axis? Stonehenge’s sarsen stones also have an Irish connection, according to Geoffrey of Monmouth: they come from Mount Killaraus, possibly in County Kildare., and even if this is not rooted in fact, the connection with Ireland in legend is there at least.

Rather than explore the other Michael feast day sunrises from Skellig straight away, I decided, for some reason, to see if this line could be extended beyond Stonehenge. As a straight continuation, along the same azimuth, it yielded nothing. But along a new azimuth, this time, the azimuth of sunrise on Michaelmas morning at Stonehenge, the line went to the centre of the city of Brussels, capital of Europe, and home of the Cathedral of Saints Michael and Gudula (originally dedicated solely to the Archangel).

Was this another Michael alignment - Skellig to Stonehenge, Stonehenge to Brussels? How odd to find a connection between England and Brussels just weeks before Brexit. And also a link with Ireland, a line drawn from Ireland, a line connecting the most complicated aspects of the Brexit conundrum, through England and to Brussels. This line, however, is the opposite of a border, it's a line that brings places together. You can't help but notice sunrise in Ireland points to England, or that sunrise in England points to Brussels, and just as Ireland sought to escape England, England (or some of it) seeks to escape Brussels. Can any meaningful connection can be made between Ireland, England and Brussels, now (despite the political impasse) or 6,000 years ago (despite the apparent technical limitations of the time)?

Sunrise on Michaelmas morning in Brussels leads then to Aachen, a German city, but once the capital of the French emperor Charlemagne. There's a chapel dedicated to St Nicolas and St Michael in the cathedral, so again the Michael connection remains. The azimuth of Michaelmas sunrise in Aachen takes us close to Bonn Minster, the most important church in one of Germany's oldest cities, the old capital of West Germany, but the Michael connections are wearing thin here. I can't see anything much to do with Michael, apart from a statue of the Archangel in the university. There is a church dedicated to Saint Michael, but it seems to be a modern structure. From Bonn, I could find no Michael connection further East that matched Michaelmas sunrises.

Still, there is an impressive precision to this Michaelmas line. Does Michaelmas mark an important day thousands of years old - at least as old as Stonehenge, the oldest structure on this line? And what is the logic to this line, the places on it? Its lynch pins, are sometimes very far apart and sometimes really quite close. The other time of year when the sun rises at this azimuth from Skellig Michael is the 15th March. That's just two days before St Patrick's day.

The solstices and the equinoxes have been linked many times with the orientation of ancient structures, all around the world. For example, Newgrange in Ireland is designed to let in a beam of light from the sun at sunrise during the couple of days of the winter solstice, so as to flood the central chamber with golden light at dawn. Perhaps too, though this is less publicised - because the rising winter solstice sun is the beating heart of the Irish tourist board - just before sunrise, the light of Venus shines though the light box. If Newgrange is one of the best known solstice markers, then the Sphinx at Giza is probably the best known equinox marker, as it gazes due East. And of course Stonehenge embodies both solstice and equinox, as well as lunar motions, which, together, form the station stone rectangle, as only at the latitude of Stonehenge do major lunar standstills and solstices create lines which meet at a right angle. Many ancient structures are associated with sunrise (or sunset) at one of the quarter points, solstices or equinoxes. In Europe, medieval churches are often orientated towards sunrise on the day of the feast of the saint to which they were dedicated to, and this practice seems to have stopped well before the twentieth century, perhaps marking an important star linked with the saint. Today, no one gives a second thought to where in the sky the sun will appear, over which landmark, into which constellation, at which leg of the sun's journey between solstice points.

It seems that at Skellig Michael, Stonehenge, Brussels, and Aachen the 29th of September (in our epoch) is a key date as it links all these places according to sunrise there. It's a Michaelmas line, or series of lines, as from each successive point it's course changes slightly. It is perhaps a series of sighting points, from a long lost astronomically obsessed culture. Another important aspect of marking a date with sunrise in a particular place: it is latitude dependant, just like the station stone rectangle at Stonehenge I mentioned earlier. The first moment of sunrise at Skellig on the 29th of September has a different azimuth to the first moment of sunrise at Stonehenge - only slightly different, but different nonetheless.

With this in mind, I decided to head back to the Mont Saint-Michel (on Google Earth of course...) and see what I could find.

My head buzzing with all the possibilities, I decided to check something slightly different there. I knew about the 8th of May being an important feast of Saint Michael in France and I had an idea: how about checking what azimuth the sun rose in, on that date, at the Mont Saint-Michel, in Normandy?

Phi Days

For some reason, in my excitement, before I checked the sunrise azimuths, I had a look at the number of daylight hours there were. I'd been reading the Book of Enoch, possibly to help me drift off to sleep - it's not a page turner - and there's a bit when they discuss the ratios of day to night: 7 parts to 11 parts, or 9 to 9 parts, always a total of 18 parts. I thought that was an unusual way of looking at time, and that it may have been commonplace a long time ago. So I checked the ratio of day to night at the Mont Saint-Michel on the Saint Michel feast day.

I found there were 14 hours 54 minutes and 47 seconds of daylight at the Mont Saint-Michel, this year, on the feast of Saint Michael, which converts into decimals as 14.913 hours. Divide 24 by this and you get a rather fantastic 1.60933. Surprisingly close to Phi! (Phi = 1.61803...) I was not expecting that. Is there something close to a golden ratio between daylight and darkness on the feast day of Saint-Michel in Normandy?

In fact, the 7th of May was an even better match with a ratio of daylight to darkness of 1.61462, and the 6th of May, better still, has a ratio of 1.620045 - the Phi ratio belonging somewhere in the middle of the 6th and 7th May. Switch over to another year, the 7th May 2023 for example will have 14 hours, 51 minutes and 57 seconds of daylight, which gives a ratio of darkness to daylight of 1.61435, which is also close to Phi.

I got the sunrise azimuth for the 8th May, 62.67°, and the 7th May, 63.11°, and I traced lines accordingly on Google Earth from the Mont Saint-Michel, and they both ran a few streets north of the two churches in the nearby town of Avranches, Notre Dame des Champs and the Saint-Gervais Basilica. The azimuth for the 6th May sunrise is 63.57°, and the line from the Mont Saint-Michel to both churches in Avranches is 63.49°. So it seems that both the Phi ratio of daylight to darkness and the orientation of the line from the Mont Saint Michel correspond to something just between the 6th and 7th of May, the same as the Phi ratio of hours of darkness and daylight.

Then I remembered reading about a mini Michael alignment which ran from Mont-Dol, in Brittany, to the town of Avranches in Normandy, via the Mont Saint-Michel, and sure enough, extended south-west, this line ran near Mont-Dol. And here was this other Michael alignment, corresponding to the azimuth of sunrise on the 6th/7th of May, a day (or two) before the feast of Saint Michael.

The line between Avranches and the Mont Saint-Michel with Mont-Dol isn't perfectly straight but there is one detail that is worth mentioning: the distances between the chapel to Saint Michel on Mont-Dol and Mont Saint-Michel, and between Mont Saint-Michel and the Basilica in Avranches are in Phi ratio. What's more, extended further north - east, I found that the sunrise azimuth line that linked the Mont Saint-Michel to Avranches goes all the way to Rouen. And this ties in to the places on the Saint Michael Mount - Mont Saint-Michel alignment in this way: Rouen Cathedral and Abbey are exactly the same distance from Stonehenge as are Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel. Also, a Michaelmas sunrise line from Rouen extends over more than eight hundred miles to the chapel of Saint Michael in Budapest, on the river island of Saint Margaret, and also goes a hundred yards away from the church of Saint Michael in the German town of Burgstetten.

The 8th of May is the actual feast of Saint Michael, but at the Mont Saint-Michel it seems that the 6th / 7th May are the important dates. In fact, the best fit for a Phi day on the 8th May is at a latitude around fifty miles further south, such as the city of Orleans. The actual Phi day at the Mont Saint-Michel, or Phi days - the 6th and 7th May - fits the alignment between Mont-Dol, Mont Saint-Michel, Avranches, and then extends further to Rouen.

'The path, winding like silver, trickles on', wrote Edward Thomas. Here, the path seems to be made not of water but of light, not of silver but of gold. What other sunrise paths might there be? The 7th May at the Mont Saint-Michel has close to a Phi ratio between day and night, taking the exact moments of sunrise and sunset as the start of day and night. It's a 'Phi day'. So what are the other Phi days at the Mont Saint-Michel? I had another look at sunearthtools.com...

On the 7th May and the 6th August, the sun rises at azimuth 63.11° and 63.04° respectively (2019 figures). On the 26th January and the 15th November, the sun rises azimuth 118.04° and 117.5°respectively. All four days have close to Phi ratios between darkness and light.

Le Mans is sometimes considered a contender for being on the Michael Apollo Artemis alignment, and the azimuth from the Mont Saint-Michael to Le Mans Cathedral is 118.24°, almost ninety miles down the road. That's just 0.20° off the 26th January (a Phi day) sunrise azimuth for 2019, and only 0.10° for the 2020 value. If you wanted to mark the sunrise azimuth for a winter Phi day from the Mont Saint-Michel with a cathedral, you couldn't get much more exact than the location of Le Mans cathedral. Is the whole alignment across Europe a series of Phi lines? I was back to where I had started, trying to make sense of the Michael alignment from Skellig though Europe. Only now I had a clue about how to approach it.

The European Michael alignment as a series of Phi day sunrise lines

I went back to Skellig Michael. I found that there, the Phi dates were (for 2019): 1st / 2nd February, 1st May, 12th August, 9th November. (There is never a day with an exact match between the ratio and 1.618, you have to pick the closest one or two, every day has a few minutes more or less daylight than the previous, or hope next year or the year after has a better match). The closest of these days to a winter Phi day is the 9th of November, with an azimuth of 116.66° , which is close to but a little greater than the Skellig - Michael Mount line azimuth (115.40°). I think it's close enough to consider a connection between the two. A closer match would be the 7th of November, with a sunrise azimuth of 115.65°, but there are 8 minutes too many of daylight on that date to make a Phi ratio with darkness. The azimuth of a line running from Skellig to the Mont Saint-Michel is 114.95°.

When I got to look at Saint Michael's Mount, there was another surprise. Yes, the winter Phi day sunrise line (the closest match being 117.66°), pointed closely to the Mont Saint-Michel (azimuth 118.32°). I was expecting that. And the sunrise line was slightly to the north of the presumed target, the Mont Saint-Michel, which could possibly be explained by the sun travelling south as it rises. The Phi days at Saint Michael's Mount are, for 2019: 4th May, 8th August, 12th November and 29th January - For Star Wars fans: May the Fourth be with you - first, a Skellig Michael connection and now a Michael Mount connection!

However, it was the summer Phi day azimuths that caught my attention. The summer Phi day sunrise line azimuth at Saint Michael's Mount is 63.63°, for this year. Saint Michael's Mount to Stonehenge is 63.96°. In 2025, on the 3rd May, there are 14 hours and 50 minutes of daylight at Saint Michael’s Mount, which is very close to a Phi ratio, and the sunrise azimuth is 63.85°. The azimuths are almost identical. If anything, the fact that the sunrise line was slightly to the north of Stonehenge gave room for the sun to rise a little over the horizon and travel southwards as it rose. So here, once again, Stonehenge makes a surprise entrance into the Michael line. Firstly, it is because it is equidistant from the two Michael Mounts, the one in Cornwall, the other in Normandy. Secondly, it is on the Michaelmas sunrise line from Skellig, all the way over off the west coast of Ireland. And now, this: a summer Phi day sunrise from Saint Michael's Mount points to it. There seems to be no doubt about Stonehenge's connection with the line formed by Skellig, Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel.

There is another famous Michael alignment which runs across the south of England, from Land's End to Norfolk, and sort of via Saint Michael's Mount, Glastonbury, and Avebury - the line is not completely straight. It’s a line which reached the British mainstream in the sixties and continues to thrive on the internet. But it’s a little too bendy, and little too hazy really, for me. It doesn’t fit with the precise pattern of lines seen so far. So a question I asked myself was this: what is the orientation of a line from Saint Michael's Mount to Avebury and Glastonbury, and what date would a sunrise azimuth matching this be on? Saint Michael's Mount - Glastonbury Tor is 58.70°, and to Avebury, 58.82° - also, St Michael's Mount- Burrow Bridge 58.64°, and Saint Michael's Mount - The Hurlers stone circles: 58.31°, they are almost perfectly aligned, much much better than the vague line running from Land’s End to Norfolk, which in fact misses Saint Michael’s Mount completely. In fact I'm not sure why you’d want to include places such as Land's End, or other ancient stone circles or Michael churches, when these five, Saint Michael's Mount, The Hurlers, Glastonbury Tor, Burrow Bridge and Avebury are so closely in line. All but Avebury and the Hurlers have Michael connections: there are ruined churches dedicated to Saint Michael on the tops of Burrow Bridge and Glastonbury Tor, and the castle on top of Saint Michael's Mount has a chapel, and was once a sister house of the Mont Saint-Michel abbey. So there are two important lines emanating from Saint Michael's Mount: the one to Stonehenge and the one to Avebury. The best fit for this second Avebury alignment is the 15th May - but what is the significance of this date?

If you divide the number of days between the summer solstice and the spring equinox by Phi, you get a date close to the 15th of May. The spring date with equal night and day at Saint Michael's Mount seems to be, according to Sunearthtools.com, on the 18th March, when you get 12:01:14 hours daylight (as opposed to the so-called equinox, which doesn't necessarily have equal day and night, despite the name). Incidentally, Saint Patrick’s Day simply marks the date of equal day and night at the latitude of Skellig Michael, and sunrise on that day at Skellig leads just south of Avebury to Milk hill barrow and white horse. Summer Solstice at the same latitude is on the 21st June, with 16:23:34 hours sunlight. That's a period of 95 days. Divide that by 1.618 and you get 58.714, which, from the 18th of March, brings us up to the 15th day of May (or the 15.714th to be exact!). So the 15th May marks a Phi point between equinox and solstice. Perhaps that's the reason for it's importance, it’s the best I could find anyway.

Whatever the reason, the English Michael line is oriented to a 15th May sunrise, and a 15th May sunrise as seen from Skellig Michael shares an azimuth with a line that runs through the heart of Dublin all the way to Durham Cathedral.

France and England both have (at least) one summer Phi day sunrise line which links sacred places, some of which are dedicated to Saint Michael. The French one links Mont-Dol, the Mont Saint-Michel and Avranches Basilica, and the cathedral and abbey at Rouen. The English one links Saint Michael's Mount and Stonehenge. What about Ireland? Does Skellig have a summer Phi day alignment, or even a 15th May alignment? Well, yes, as a matter of fact, it does. I drew the 15th May sunrise azimuth from Skellig on Google Earth and the line went through Knocknabansha, a high peak whose name means fairy mountain, the historic centre of Dublin (and who knows what was there before the Vikings founded the city), and, unbelievably, Durham Cathedral.

More than just a mere coincidence, this all points towards towards a human construct. More than just a line, this seems to be a few strands of a network, not just a single axis, an entire network of alignments, directed by a handful of sunrise azimuths.

I was surprised to see that the May and August Phi day sunrises link Skellig Michael to the Rock of Cashel, and the line also goes right over two of the highest peaks in Ireland, and then on to the sacred island of Anglesey.

Michael and Patrick

The Rock of Cashel is dedicated to Saint Patrick. It is a holy site in Ireland, the round tower on it is over 900 years old, and still stands, but the cathedral was sacked by English Parliamentarian troops in the 17th century and is still in ruins. A new cathedral was built in the town centre instead. It's an impressive place. I thought to myself: wouldn't it be nice if it had been dedicated to Michael, then it would fit into the network really nicely. Then I recalled something I had watched on You Tube one time, about a constellation being the possible source of the St Patrick story - Sagittarius it was I think, slaying a dragon-like constellation on the 17th March? I remember thinking that it was pretty similar to the Michael story, that maybe Patrick and Michael were two offshoots of the same primary divinity or figure. And now I find that a major site dedicated to Patrick is on a line projected from a Michael site. Then there's those snakes Patrick gets rid of, not unlike Michael fighting his dragon (or George for that matter) .... Is this a Michael line or a Patrick line?

Are Michael and Patrick potentially the same figure? My initial idea was that if Patrick could be considered as derived from Sagittarius, could Michael be too? The person behind that YouTube video was David Warner Mathisen, who writes : 'As the earth rotates on its axis towards the east, the stars we see appear to rotate towards the west, which is why Scorpio (located to the west of Sagittarius) appears to be "driven out" by Sagittarius as the earth turns throughout each night -- and why Scorpio will eventually sink out of sight into the western horizon before Sagittarius follows later on.' So, each year, around March, the constellation Scorpio is pushed under the horizon, and to the left of this monster is the archer Sagittarius, doing the pushing, and above it are Hercules and Ophiuchus, bastions of masculinity, always ready to strike. Any one of these could be the victorious slayer of Scorpio, the one who sends evil and darkness packing for ever, or at least for a few months or so. Sagittarius pursues the constellation Scorpio, and is finally victorious.

I wrote to David Warner Mathisen asking him for his views - in particular, are Michael and Patrick potentially derived from the same figure? My initial idea was that if Patrick could be considered as derived from Sagittarius, could Michael be too? Or could either one be considered as any of the constellations that routinely send Scorpio packing under the horizon... Hercules, or Ophiuchus…? It seemed to me that the important thing was that someone was defeating Scorpio, someone was slaying the snake or dragon. David got back to me, with lots of helpful comments, and said that in his view Michael was more likely to correspond to the constellation Ophiuchus, not Sagittarius. But then he also said that maybe after all, Patrick should be considered not as Sagittarius, but as Ophiuchus too - the same as Michael! In any case, he was open to the idea of a correspondence between the two, in terms of matching constellations.

There is a clear link between these two dragon or snake slaying figures, Michael and Patrick (as well as George, Arthur, Apollo, Artemis, etc...), just as there is a clear link between the celestial dragon or snake slaying figures of Sagittarius and Ophiuchus (as well as the constellation Hercules, and Virgo, and indeed there are paintings and sculptures of the Virgin Mary standing on a snake). And on Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel, there are stories of giants being killed there, by heroes such as Jack and Arthur. There is also a legend in a German manuscript, of Irish origin, of Patrick himself slaying a snake on Skellig, with the assistance of Saint Michael, who appears to him.

The Significance of Phi

All living things, at every level, from the micro to the macro, from the individual to the group, are infused with, or controlled by Phi. It is the number of life itself. Things grow in Phi ways, and not just nautilus shells. For those who are religious, and are also aware of the pervasiveness of Phi, it must be quite significant, a sort of divine number (or function). The sun is also a symbol of life, and together with Phi, it forms a symbolic duo. The idea of dividing up days into daylight and darkness reflects the duality of a manichean world view, where the forces of evil must be defeated by the forces of good, just as the sun defeats darkness each morning, perhaps with the assistance of the constellation in which the sun rises. The significance of a day on which darkness and light are in Phi ratio becomes clear: it is a divine day. I don't think you can overplay the significance of Phi in the ancient world. Phi is present in the Great Pyramid of Giza, and the layout of the pyramid complex. In Ireland, I discovered that the Hill of Tara, Knowth and Monasterboice are precisely aligned and separated by a Phi ratio. I also found that Mont-Dol, Mont Saint-Michel and Avranches Basilica are separated by a Phi ratio. At Stonehenge, Phi is present in the geometry of the station stone rectangle and the Aubrey circle. It’s in Christopher Wren’s London too, and it seems he also incorporated Phi day sunrise and sunset azimuths into his plans too - see below. I’m sure there are many many more examples. Once you start looking for it, you find it.

Christopher Wren used summer and winter phi days to create his network of churches around St Pauls' Cathedral, the London Mithraeum, and the Freemason's Hall.

He also used Michaelmas sunrise lines, and places churches dedicated to Michael accordingly, as well as to Mary.

Is the ankh a symbol of Phi?

(some do have a longer stem than pictured above however).

Phi symbolises life, but it is also a way for the select few who understand this, or who, at least, are taught this, never mind what they understand, to create a social hierarchy based on knowledge. Power, in the form of influence and wealth, can be distributed according to this hierarchy. Though all power relies on violence, or the threat of it, perhaps violence is not enough. Perhaps understanding Phi is a sort of personal atonement, a sort of ticket to self-worth for the people who control and design the world. There is pleasure to be taken in trying to grasp Phi. Maybe there have been times when encoding Phi into designs wasn't just for the eyes and ears of the select few who'd been chosen to be part of the secret, but it seems to me Phi is unfortunately nearly always linked with secrecy and elitism, and very probably, sexism. I think Phi has been used for millennia in design, from the smallest scale, say the ankh, to the largest, say the placement of sacred places in relation to each other.

If the internet can be made to bring about a redundancy of this elitism, then that's a positive thing.

Scott Onstott observes in a blog post on his fantastic website www.secretsinplainsight.com/location-location-location/ that the distance between Stonehenge and the Western Wall in Jerusalem is 33.33 degrees. This is also azimuth 111.17 degrees from Stonehenge, and this is equivalent to 180 divided by 1.619 (close to Phi). So two of the most sacred places in the world are linked by a Phi controlled angle. If you are happy that 1.619 is close enough to Phi, and if you accept that Stonehenge is located according to Skellig Michael, Saint Michael's Mount and the Mont Saint-Michel, as well as Lundy, then the Skellig - Mount Carmel line, by its very nature a succession of Phi day sunrise lines, then Jerusalem's location could be seen as a Phi location, derived from the Michael axis, even though it's not on it.

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi is on the winter Phi day sunrise line from Stonehenge, so perhaps it too can be considered to be derived from the Michael alignment from Skellig to Mount Carmel.

Stonehenge - Delphi: azimuth 117.18°, and winter Phi day sunrise at Stonehenge 10 November closest match is 2025) 117.04°. Perhaps it's a coincidence that Stonehenge's winter Phi day sunset azimuth line (242.78°) goes to Lake Titicaca, over 6,000 miles away.

Back to the Michael Apollo Artemis alignment

So where does this Michael Apollo Artemis alignment go then? Skellig to Saint Michael's Mount, then on to Mont Saint-Michel and then Le Mans, each time following close to the line of a winter Phi day sunrise. The northern part of the European Michael line seems to be a succession of points on winter Phi day sunrise lines. And from each of these points, there are summer Phi day sunrise lines radiating out of them to the north east, each with significant places on the line: Skellig Michael to the Rock of Cashel, Saint Michael's Mount to Stonehenge (via some interesting megalithic features such as Merrivale, Soussons Down Cairns, Grimlake Cist, and Easdon Hill), Mont Saint-Michel to Avranches Basilica and Rouen Cathedral and St Ouen Abbey, and Le Mans Cathedral to Chartres Cathedral and Reims Cathedral. Each of these places, with the exception of Stonehenge and Saint Michael's Mount, which was an abbey once, has a famous cathedral, and many are UNESCO world heritage sites (Aachen, Mont Saint-Michel, Stonehenge, Skellig Michael, Durham Cathedral, Chartres Cathedral, and Amiens Cathedral). Then there are the Michaelmas lines, the 15th May lines... We've seen several 15th May alignments, for example Skellig to Dublin and Durham (and Durham Cathedral is significant in that it is the same distance from Mont Saint-Michel as is Skellig Michael, and also almost perfectly North of the Mont Saint-Michel), and Saint Michael's Mount to Glastonbury and Avebury. Then there's the 15th May line from Stonehenge to St Albans Cathedral (exact azimuth 57.69°, just 0.17° off). Saint Alban was executed on the hill where the cathedral and abbey now stand sometime in the 3rd or early 4th century. The place was important to pre-Christians, and St Albans was the Roman city of Verulamium, built next to a Celtic settlement.

There is a whole network to be uncovered, and which, for the most part, survives only in medieval religious buildings, but the network itself has to be as old as Stonehenge.

This suggests a transmission of knowledge over centuries, as some of these places are definitely of Neolithic importance, and the great cathedrals are mostly Norman or French, in the areas I've looked at so far. I didn't expect to find such precision with these lines over long distances (over time as well as space!). Was this network laid out thousands of years ago, and remembered as a whole, with its logic, or were the individual places that formed part of the network simply re-adapted to Roman, and then Christian times, and knowledge of the system as a whole lost?

I have no idea how the precision of the network might have been achieved, but I don't doubt that it was. It's as if the builders of Stonehenge had Google Earth. They must at the very least have had amazing star charts, and understood the sky as a clock, to determine longitude with precision.

Here are some of the most interesting alignments I have found:

For daylight and darkness to be in Phi ratio, you'd need as close as possible to approximately 9:10 or 14:50 hours of darkness or of light, the time between sunrise and sunset. You can look this up on sunearthtools.com. The days in winter when this occurs on Skellig is the 9th of November (or the 1st of February). The closest sunrise azimuth for a winter Phi day at Skellig is 116.81° (value for 9th November 2026), which is close to, but a little greater than the Skellig - Michael Mount line azimuth (115.42°). At Saint Michael's Mount, the winter Phi days are the 12th November and 29th January, with a sunrise line (the closest match for a Phi ratio being 117.43°, value for 12th November 2024), pointing closely to the Mont Saint-Michel (azimuth 118.32°). On the Mont Saint-Michel, a winter Phi day sunrise azimuth is 117.94° (value for 16th November 2027), and the azimuth linking it to Le Mans cathedral is 118.22°. Winter Phi day sunrise azimuth at Le Mans is 118.26°, and this bearing leads us to Saint Michel-de-Volangis (azimuth 118.28°), via Paray-le-Monial, and on to the Sacra di San Michele, azimuth 118.02°. Winter Phi day sunrise azimuth 119.46° from there (value for 26 November 2022) leads to the Santuario di San Michele in Recco, azimuth 119.33°, winter Phi day sunrise in Recco is 119.8° (29 November 2019 value), which leads to the Chiesa dei Santi Jacopo e Filippo, once dedicated to Michael, in Certaldo, azimuth 199.99°, and another Michael church in Gaiole, in Chianti, azimuth 199.61, and another again in Eggi, in Spoleto, azimuth 120. Winter Phi sunrise there is 120.61°, value for 7 December 2019, which leads to Larino, which has a via San Michele, Azimuth 120.47°, and Cathedral 120.62°. Winter Phi day sunrise in Larino is 121.1°, 15 December 2019 value, and goes to .. well, nowhere. A few miles further south of Larino, and there are no more winter Phi days, as the latitude no longer permits them from here, going south. However, a town near the Phi day border, and near Larino, with a church of Saint Michael, is Foggia, and this is on a summer solstice sunset line from Delphi. Delphi is a place where the summer solstice is also a Phi day, which may explain the importance of the site. South of Delphi there are no more summer Phi days (or at least there wouldn't have been in 1,500 BCE, according to Stellarium. The current Phi day border is just over 14 miles south of Delphi.)

A summer Phi day sunrise azimuth on Skellig leads precisely to the Rock of Cashel, in Tipperary, a rock on top of which is a ruined Cathedral dedicated to Saint Patrick, and Anglesey. A summer Phi day sunrise azimuth at Saint Michael's Mount leads precisely to Stonehenge. The summer Phi day sunrise line azimuth at Saint Michael's Mount is 63.63° for this year and the closest match for a Phi Day ratio is in fact in 2025, on the 3rd May, there are 14 hours and 50 minutes of daylight at Saint Michael’s Mount, which is very close to a Phi ratio, and the sunrise azimuth is 63.85°.

A summer Phi day sunrise at the Mont Saint Michel leads to Avranches and Rouen Cathedral. The cathedrals in Le Mans, Chartres and Reims are aligned, on a 62.41° path, which is Phi day summer sunrise from Le Mans.

A winter Phi day sunrise line from Brussels goes to Mount Carmel, via Munich (a mile to the north of the cathedral dedicated to Saint Michael), and in the other direction (+ 180°) takes you to the centre of Bruges, and then on through England via Colchester (an important Roman city), then to Holyhead, and to Mayo in Ireland.

A line links Stonehenge to the Cathédrale Saint-Michel in Carcassonne, via Notre-Dame-de Bayeux Cathedral, Saint-Patrice-du-Desert, Saint-Michel-sur-Loire, and one of France's best loved places, Rocamadour, where the archangel's sword is embedded in a rock face.

A winter solstice line from Stonehenge leads to Rome, about a mile from the Vatican City, and just under two miles from Castel Sant’Angelo, the mausoleum turned into a church dedicated to Michael. This same line goes through the Église Saint-Michel in Dijon, in France, and right by the Église Notre-Dame, and the city’s Cathedral, also less than a mile from the Basilique of Saint-Denis in Paris, and a few hundred metres from the Château de Gisors, dating back to at least the 6th century.

The English Pillars of Hercules, otherwise known as Hartland Point, in Devon, are precisely aligned with Stonehenge and Canterbury Abbey, one of the first Pagan places of worship to be transferred to the Christians in England, previously on the site of the present Abbey.

There are 15th May alignments from Rouens Cathedral to Amiens Cathedral, from Tumulus Saint-Michel to the Kerkado Tumulus, Béquerel, Vannes Dolmen, Kernours, and Rennes Cathedral, and from Kermario to Rennes Cathedral, also from Chartres Cathedral to Meaux Cathedral. The 15th May seems to be a point in the calendar which is at a Phi division between spring equinox and summer solstice.

The winter Phi day from Rouen Cathedral goes to Delphi, in Greece, and the summer Phi day sunset just south of Lundy island. The winter Phi day from Chartres Cathedral leads to Alexandria and the Giza plateau, via the Klein Matterhorn. The winter Phi day from the Tumulus Saint-Michel at Carnac goes to Limoges Cathedral. And from the Menhirs de Kerdeff at Carnac to le Menec, Tumulus Saint-Michel and Limoges Cathedral.

A Michaelmas sunrise line from Chartres Cathedral goes to the palace of Fontainebleau and Epinal, and from the Tumulus Saint-Michel, a Michaelmas sunrise line goes to Angers and Tours Cathedrals.

The cathedrals in Le Mans, Chartres and Reims are aligned, on a 62.41° path, which is Phi day summer sunrise from Le Mans.

A summer Phi line from Chartres Cathedral goes to Reims Cathedral and on to the Abbaye d'Orval. A Summer Phi line from the Tumulus Saint-Michel at Carnac goes to the Dolmen de Kervilor Mane Bras, and the Montneuf Menhirs, from Kermario to the Petit Menec and Kernours Tumulus.

A Michaelmas line (varying between 92.4° and 92.81° from year to year) from San Miguel de Breamo, an old Templar church near A Coruña, in the north of Spain, (and which is also aligned with Santiago de Compostela and Stonehenge), can be traced to the abbey of San Michel de Cuxa, and an Eglise Sainte Marie which goes through or near: a church of San Miguel at Lazkao Gipuzkoa, an Ermita San Miguel, and an Iglesia de San Jorge next to an Iglesia de Santa Maria, and a small village called San Miguel, the Ermita San Miqueu in the Pyrenees, and two Templar chapels (Lus-Saint-Sauveur, on the Prime Meridian, and Aragnouet), as well as various other mountain shrines and hermitages.

A summer solstice sunset line from Delphi goes through Makelaria monastery, San Michele Salentino, near San Michele, Bari, Foggia, Cathédrale Notre-Dame-Du-Puys and Rocher Saint-Michel d’Aiguilhe, and on to Mexico, thirty miles or so from the Olmec Pyramid at La Venta.

The Monte Sant’Angelo sanctuary is not on the winter Phi Day alignments from Skellig. It is however at a latitude where the winter solstice hours of daylight are close to being in Phi ratio with the hours of darkness (it’s just over a minute off). A winter Phi day sunrise line from Chartres goes to a mile south of Monte Sant’Angelo and seven miles to the south of Ancient Heliopolis in Cairo. (total distance over 2,000 miles).

The temple of Delphi is aligned with the temple of Artemis on the island of Delos, and Mount Carmel, also passing near the town of Archangelos on Rhodes.

Skellig Michael, Chartres Cathedral and Ancient Heliopolis are aligned on a 17th of February sunrise line from Skellig.

Ancient Heliopolis, Alexandria, the Basilica San Michele Archangel, Sorrento, the Grande-Miquelon island of St Pierre-et-Miquelon, the White House in Washington, the vicinities of Monticello and Mount Mitchell, and the churches of San Miguel, Salamanca and San Miguel de Allende, in Mexico, are aligned. (Via a few other Michael churches in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Bristol, a couple more in New Jersey, at Cherry Hill and Greenwich. However, there are lots of other Michael churches near enough to the line, in the US part, so it may just be chance that they are on the line.)

This last line is very similar to a line I just discovered on Scott Onstott's website: "The oldest standing obelisk in the world, in Heliopolis Egypt, is in a great circle alignment with the Lighthouse of Alexandria, Egypt and the replica Lighthouse of Alexandria, Virginia (333 feet high), officially titled, “The George Washington Masonic National Memorial.”

This last line goes right through the gardens at Monticello, and the summit of Mount Mitchell, and in terms of those two places is a much better fit, but it misses the island of Grande-Miquelon, passing instead through St Pierre. See http://www.secretsinplainsight.com/location-location-location/.

Some conclusions

Are many of our cities and sacred places where they are because some Stone Age people laid out a grid over the landscape, that we have inherited?

This Michael Apollo Artemis axis is a bit of an enigma. Rather than a single line, anyway, it seems to be a mass of lines. If there is anything in these Phi day and Michaelmas alignments, they presuppose another aspect of a long lost scientific and technical sophistication, which may have pertained to many civilisations, across the globe. This sophistication has been revealed already in the work of many researchers, perhaps most famously by Graham Hancock.

You can speculate on what the Normans knew, and how they exploited a geographical geodesic system which is at least as old as Stonehenge by building great cathedrals and abbeys on key sites. Why did the Normans expand their territories across the very countries the Skellig to Mount Carmel line crosses? You can also speculate on how well their possession of this knowledge sat with the Vatican.

I think that if we look at some of the events that are happening around the world just now, it is not difficult to believe in the fragility of civilisation, however sophisticated a civilisation might be. It can disappear quite suddenly, or simply be battered in such a way that it takes a generation or two to recover. Spare a thought for the people of the Bahamas, right now. I listened with interest to the novelist Robert Harris being interviewed by Jon Snow, in the context of a Brexit worse case scenario, speaking of London being perhaps only six meals away from starvation. His new novel is about a post apocalyptic world in which we have no internet, everything falls apart, and people use churches as meeting places. You can imagine how the buildings of a religion, or at least the sites they are built on, can outlive by many centuries, and perhaps millennia, the religions that first built them. It is not at all difficult to believe that thousands of years ago, sophisticated civilisations have existed. To find them, you have to look for them.