Orientalist frames: Part 1

There is a slight frisson now around the term ‘orientalist’, since it is seen as implying an exploitative, touristic view of exotic places and people, depicted from the outside without empathy or understanding, and reliant on the superficialities of architecture and costume to fill in the gaps in vision which this approach presents. This may well be true of the crowds of minor artists in the 19th and 20th centuries who followed where better men had gone in a genuinely inquiring spirit, and who turned out swathes of pot-boiling landscapes, costume studies and interiors of harems in order to cash in on what had become a fashion.

However, there were a great many artists who did engage with whom and what they found on their travels; who painted scenes and people in the same way that they would have painted in other locations which were new to them, and who (later on) designed frames for their work which were intended to display it appropriately. There were also numerous architects and craftsmen who absorbed in varying degrees the influences of styles foreign to their own, and remade them in local contexts, producing a swathe of frames which are indebted for their profiles or their ornaments or their surface decoration to models originating in the near east or in Africa.

This is Part 1 of an overview of these frames, decorated with ornament derived from Islamic sources (Part 2 will look at frames created as part of a whole work of orientalist art): a brief introduction to work from the 10th to the 18th century.

Early Islamic influences on western frames

Sections of a minbar or pulpit from the Andalusian Mosque, Fez, 979-85, carved, turned and painted cedarwood, back: 146 x 75 cm., panels, 56 x 20.6 cm. [not shown to scale], Dar Batha Museum, Fez, Morocco. Photo: © Discover Islamic Art/ Museum with no Frontiers (MWNF)

The Islamic influence in Europe, in terms of architectural and surface decoration, was earliest and most profound in Spain. The Iberian peninsular had been invaded in 711 by a commander and a governor of the Umayyad Caliphate in north Africa, rapidly capturing two-thirds of the territory previously ruled by the Visigoths, and in 717 crossing the Pyrenees into southern France. This created the kingdom of al-Andalus, depending from the unconquered northern shore of Spain and separated from the northern shore of Morocco by the Pillars of Hercules. Umayyad rule was particularly important for its long-lasting influence on the arts of Spain, and the diffusion of this influence into the rest of Europe:

‘The new Muslim rulers… accepted the pre-existing vocabulary of Hispano-Roman and Visigothic architecture… To this…were added evocations of Umayyad Syria when Damascus was the centre of the caliphate…details of plan, mosaics by artisans imported from the east, and imitations of fine marble revetment. And, finally, more recent developments from the eastern reaches of the Islamic world were reflected in the sudden spread to Spain from Iraq and Iran of fine stucco carving…’[1]

Cordobán minbar made in 1137 for the Kutubiyya mosque in Marrakesh; now El-Badi Palace, Marrakesh. Photo: المنبر المرابطي , retouched by Robert Prazeres

Later on, in the 11th century, the Almoravid dynasty brought further changes in technique and style:

‘When Cordobán woodworkers created the minbar for the Kutubiyya mosque in Marrakesh, they used decorative themes of geometric complexity which would become a hallmark of the arts of al-Andalus over the next four hundred years’ [2].

The integration of Islamic with indigenous styles gave birth to discrete genres: for example, the Mozarabic style of Christians living under Muslim rule, and then of those who moved northwards to escape it during the 10th century, taking with them the structural forms and orders and the polychrome ornament with which they had been familiar. Later on, the Mudéjar style became important, fostered by Muslim craftsmen, architects and artists working under Christian rule as the various regions of Spain were taken back from their Islamic governors [3].

Beatus, Presbyter of Liebanus (text; c. 776) and others; Maius (calligraphy and illuminations; d. 968), Commentary on the Apocalypse, c. 945, clockwise: fol. 3 recto, fol. 109 recto (detail), fol. 23 recto (part), fol.77 recto (illustration), fol. 133 recto (page ornament); The Morgan Library & Museum

A vivid encapulation of the Mozarabic style is found in the Commentary on the Apocalypse by the 8th century Beatus, Presbyter of Liebana, and others, written out and illustrated in 10th century Léon by Maius of Tábara, with more than a hundred miniatures as well as decorated initials and page ornaments. The monastery of San Salvador de Tábara was the home of a scriptorium where various copies of Beatus’s Commentary were produced; the version in the Morgan Library is thought to be the earliest.

Many of the scenes from Revelations are presented on the page set into patterned aedicules with horseshoe-arched tops, columns and leafy capitals – both arches and stylized capitals being immediately recognizable from Moorish architecture in Spain [4]. These aedicules and the rectilinear borders of other images (which sometimes have inner sub-borders) are decorated with guilloches, interlacing, geometric frets, stars, undulating leaves, and foliated heart-shapes and trefoils; there is also a tondo ‘frame’ decorated with stars, and page ornaments including – in the image above – an oblong like a box altar covered in daisy-like rosettes.

Box altars

La Seu d’Urgell workshop, frontal of a box altar from Sant Martí d’Ix, Alta Cerdanya, 12th century, pinewood, varnished metal plate and polychrome, 90.5 x 155.4 cm., Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

La Seu d’Urgell workshop, frontal and side of a box altar from Sant Romà de Vila in Encamp, Andorra, first third 13th century, wood covered with cloth, stucco reliefs, varnished metal plate and polychrome, the façade 112 x 123.5 cm., Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, shown with examples of daisy and undulating foliate ornament from Beatus’s Commentary, fol. 133 recto and fol.77 recto

The same ornaments are found on the borders – the embryonic frames – of Spanish altar frontals and complete box altars dating from the 12th and 13th centuries, where similar brightly painted scrolling and undulating foliage and geometric ornaments are employed, alongside beading, roundels and daisies. Motifs of this sort were subsumed from their original source into Christian symbolism, acquiring meanings from the things they depicted (like the daisies), which could represent qualities and states, such as, in this case, the humility of Christ, and which were a long way in application from the purely decorative use of their Arabic sources.

Altar frontal, c.1310, from Nedstryn Church, Stryn, Norway; now Bergen Museum

Artists in Scandinavia and the British Isles were also aware of Byzantine art, through gifts, trade, and travelling craftsmen; so it is not surprising that the box altars and their separated frontals found in Norway and Sweden also exhibit signs of Islamic influence – although this may be indirect, passed along through its adoption by other countries en route to the north [5] .

Altar frontal, 13th century, from Komnes stave church, Viken, Kongsberg, Norway; now Oldsaksamlingen, Kulturhistorisk Museum

Cusped arches above the entrance to the Mihrab, the Great Mosque, Cordobá, and detail. Photo: Ingo Mehling

The altar frontal from Komnes in Norway is particularly interesting for its carved arcades of cusped arches, slender flaring columns and foliate ornament in the spandrels, which seem clearly reminiscent of Islamic architecture in Spain; also for the quatrefoil (rather than a mandorla) which holds the Trinity, and the daisies or rosettes on the inner dividing borders and the frieze of the outer frame. The use of vibrant polychromy and both silver and gold leaf may also be influenced by Islamic models, possibly via Spanish box altars [6].

Gothic altarpieces

Hispanic reliquary triptych from Monasterio de Piedra, Zaragoza, 1390, giltwood and painted, shown closed: 395 x 244.5 cm., each wing: 193 x 166 cm., Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid

(Top and right) a pair of carved doors, 13th century (c.1208-41), walnut and poplar with bronze and brass fittings, traces of polychrome; 300 x 112 cm. each, from the Great Mosque in Cizre, Anatolia, with detail, Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, Sultanahmet, Istanbul; with (below) the side of a minbar, 14th century, carved wood, also Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts. Photo: Ophelia2

This extraordinary reliquary altarpiece epitomizes the Mudéjar style in a sacred work, with its marriage of Gothic paintings with Islamic microarchitecture and decoration. The cusped arches in the cornice and inside the shutters, as well as the slender columns with stylized leafy capitals and the spandrels decorated with twining foliage, are – as with the arcades in the Komnes altar frontal – very close to Moorish examples (like, again, the arches of the Mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordobá), whilst the wide frieze on the outside of the shutters is painted with designs taken straight from the fretted patterns with stars and interlaced strapwork used as overall decoration for woodwork, mosaics and tiling. The double level of arches in the cornice, with higher, cusped arches alternating with smaller round arches, is found in both Islamic and classical architecture.

Reliquary triptych from Monasterio de Piedra, 1390; shown open

The two branches of art – Christian Gothic and Islamic – are seldom seen in such a juxtaposition where they each retain their own style and identity so strongly, whilst blending together successfully into a single whole. The inner façade of the altarpiece looks more conventionally Gothic at a glance, but it, too, has slim columns with flared capitals and cusped arches, and a frame of golden rosettes on a painted frieze. The central arch was intended to hold a miraculous Host, known as the Sacro dubio from its refutation of the doubts of a priest that transubstantiation – the conversion of the bread and wine of the Eucharist into the Body and Blood of Christ – physically took place; the Host began to bleed spontaneously, and was preserved, with this reliquary being built for it. The explanation of the whole event is inscribed on the top and bottom of the outer silvery frieze which runs around the contour of the closed shutter; this inscription in Gothic black letter is an analogue of the Islamic inscriptions found on doors, along friezes and around arches.

Bartolomeo Giolfino (c.1410-86), Enthroned Madonna & Child with saints, and the Coronation of the Virgin, c.1470, 380 x 187 cm., Gallerie Accademia, Venice

Bartolomeo Vivarini (c.1440-99), Pala di San Marco, 1474, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice

Portal to the Mosque of Baybars al-Bunduqdārī, 13th century, Cairo

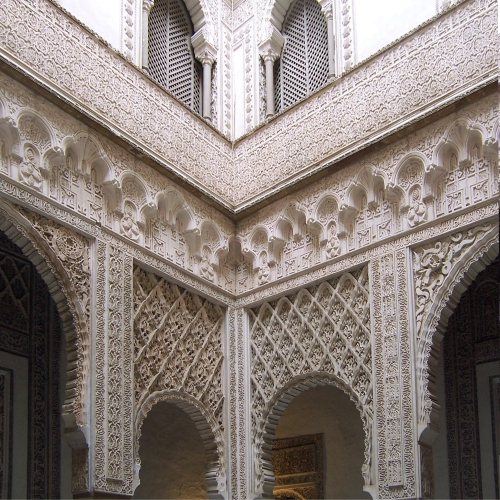

Marble carving and fretwork from the Court of the Lions, 14th century, the Alhambra, Granada

The complex enrichment of 14th and 15th century aedicular Gothic altarpiece frames, which seem at first to have developed solely as echoes of the architecture and decoration of mediaeval European cathedrals, might also – like the cathedrals themselves – be the vehicles for eastern influences and ornaments. Imported objects and migrant craftsmen were continually filtering in through the main trading routes, from the near east, from Spain in the west and from north Africa. The cusped and scalloped arches of altarpieces in the late Venetian High Gothic style were, like their Spanish cousins, influenced by the lobed arches of Islamic architecture – just as a Norwegian box altar two centuries earlier and even further away from al-Andalus and Byzantium might exhibit motifs similar to those in the Great Mosque of Cordobá.

Bartolomeo Giolfino, Enthroned Madonna & Child, detail of carved plinth

Bartolomeo Vivarini, Pala di San Marco, detail of carved plinth

Pair of doors, 14th century, from a mosque in Samarkand, Turkestan, V & A

The elaboration of pierced fretwork ornament, based on geometry and plant forms, was another legacy of Islamic styles diffusing through Europe (from Moorish Spain, but also from the near east). The decoration of these 14th and 15th century altarpieces often includes minutely-detailed fantasies of carved patterns which have evolved from Moorish traceries, and which are not found in, for instance, Florentine altarpieces of the same period.

Gentile Bellini and Mehmet II

Venice was ideally placed as a hub for trade, diplomacy, and religious pilgrimage between the Muslim, Jewish and Christian worlds of the 13th-17th centuries: a remarkable state where all faiths, embassies and mercantile operations met and exchanged ideas and objects [7]. It was also a centre (for example) for the early translation of books from Arabic into Latin and Italian, and for their publication and dissemination [8]. By the 15th century the Ottoman Sultan, Mehmet II (1432-81), who might have been considered an enemy by the Christian church (having finally conquered Byzantium), was revealing an interest in alien fashions in art as much as an openness to diplomatic relations with western Europe. He requested that a Venetian artist should be sent to paint his portrait, in answer to which Gentile Bellini travelled to Istanbul, where he spent the next eighteen months carrying out (as Rubens would do in Spain, France and England a hundred years later) the work of both painter and ambassador.

Gentile Bellini (c.1460-d.1507), Sultan Mehmet II, 1480, o/c, 69.9 x 52.1 cm., National Gallery

Panel of silk & gold-wrapped thread, Turkey, 16th century, 202.2 x 67.3 cm.; hand glass of iron inlaid with gold, ivory handle, early 16th century, Turkey, 23.8 x 12.1 cm., both Metropolitan Museum, New York

Bellini’s portrait of the sultan was composed with an integral painted frame based on the remaking of classical models by Donatello, his peers and followers. Both the cursive pattern of the carpet on the sill [9] and the foliate candelabrum design on the pilasters of the arch have some similarities to the decorative patterns of Islamic art at this period: to their fineness, detail, and use of flowing and scrolling foliage. These classical imports must have had interest for the court in Istanbul both for their samenesses and their differences, although their influence was negligible, and Bellini’s work was later sold by Mehmet’s heir.

Renaissance decoration: arabesque patterns

The carpet and painted internal frame in the portrait of the sultan are examples of western Renaissance form and ornament being taken, via an official commission, into the heart of the Ottoman court; but influence flowed more commonly in the opposite direction. The Turkish hand-glass, above, with its interlacing patterns of foliage and flowers, also has resemblances to classical arabesques (christened in Italy, during the Renaissance, from these very similarities), and the influences between the Islamic and classical versions are difficult to unfold. The very delicate scrolling, undulating or interwoven tendrils, with small leaves in S-shaped, lobed, heart and teardrop forms, as found on the glass, seem however to have produced a distinctive sub-class of decoration in the West, as well as providing the whole family with its generic name.

Venetian cassetta with panels of arabesque decoration between shaped reposes, c.1500, 36.6 x 28.9 cm., Lehman Collection, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Giovanni Bellini (fl.1459-d.1516), Madonna & Child, late 1480s, o/ panel, 35 x 28 ins (88.9 x 71.1 cm.), & detail, now in slightly later cassetta with shaped panels of sgraffito arabesque decoration on a blue ground, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Michelangelo (1475-1564), ‘The Manchester Madonna’, c.1494-97, tempera on panel, 104.5 x 77 cm., & detail of the sgraffito decoration on the frame given to it, National Gallery

Arabesque decoration in this more eastern rather than classicizing mode seems particularly suited to the art of sgraffito, literally ‘scratched’ as it was through a layer of paint and creating a design in the gold leaf revealed beneath, enabling much finer and more lasting lines of gold than could be achieved by adhering gold leaf on top of the paint or by drawing the design in mordant gold.

Gilded and polychrome leather bookbinding from Iran, c.1550, 31.2 x 18.8 cm., and detail of arabesque decoration, The Aga Khan Museum, Toronto

Mahmud al-Kurdi, ‘Veneto-Saracenic’ (Mamluk dynasty) lid of bowl, brass inlaid with silver arabesques, 15th to 16th century, Syrian or Egyptian, 10 cm. high x 14.7 cm. diam., British Museum

The sgraffito technique suits the tendril-like stems, pointed leaves, and fluent scrolls and undulations of Moorish arabesques, producing what is effectively a free-hand design derived from the carefully-organized arabesque patterns inlaid in Islamic metalwork or tooled onto the covers of books.

Renaissance decoration: interlaced patterns

There are also frames with geometric versions of the interlacing patterns which inform the panels of twining arabesques, and these seem to have been imported directly from Arabic prototypes.

Leonardo da Vinci (after; 1452-1519), the ‘Sixth knot’, 1490-1500, engraving, 29.3 x 20.7 cm., British Museum 1877,0113.365; Leonardo, Codex Atlanticus, f.5 recto, c.1480-82, silverpoint drawing, detail of bottom right corner, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan

Box with cover, 15th century, brass inlaid with silver & niello (?), 7.6 x 11.4 cm., possibly Egyptian, Metropolitan Museum, New York

For example, the knots, frets, stars and repetitive patterns which seemed to fascinate Leonardo so much almost certainly derive from (or were catalyzed by) related eastern ornament:

‘…it appears as if Leonardo based his interlaced patterns on Islamic ornamented bowls which remained very much in vogue in Italy throughout the first half of the 16th century… complicated designs in gold and silver on brass or bronze bowls and trays… the art of Islamic ornament also concerned itself with the science of geometry…’ [10]

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), vault of the Sala delle Asse, 1498, detail with interlinked and knotted golden cords, Castello Sforzesco, Milan; photo from before 1950s restoration

Giovanni Antonio Tagliente (c.1460s-c.1528), Opera nuova che insegna alle donne a cusire, a racammare & a disegnar a ciascuno, et la ditta opera sara di molta utilita ad ogni artista, per esser il disegno ad ognuno necessario, la qual e intitolata esempio di recammi, published 1512, pp. 5-6, Bibliothèque nationale de France; Internet Archive

Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, Opera nuova…, pp.7-8

These motifs – frets, interlacings, knots and complex braids – were translated into designs which filled the increasing number of pattern-books being printed, alongside panels of arabesques. They could be used, as the full title of Giovanni Tagliente’s book suggests, by embroiderers, lacemakers, calligraphers, as well as by ‘every artist’. They turn up in paintings, on textiles and tiles, but they also appear as surface decoration on frames.

Giovanni Bellini (c.1435-1516), The Dead Christ supported by two angels, c.1465-70, o/panel, 95 x 71.7 cm., & detail, National Gallery

The 16th century cassetta used to reframe Bellini’s Dead Christ in the National Gallery, although slightly later than the painting, is a perfect match for it aesthetically, in general period, and in probable location; however, the geometric fret or interlacing on the frieze (painted in mordant gilding on the black ground) may very well have been executed to echo something in the original painting it contained.

Lotto (c.1480-1556), Family portrait, 1523/24, o/c, 96 x 116 cm., State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg

Gentile (c.1460-d.1507) and Giovanni (c.1435-1516) Bellini, St Mark preaching in Alexandria, 1504-07, o/c, 347 x 770cm., Pinacoteca Brera, Milan

A similar frame, for example, might have been used for one of Lotto’s so-called ‘carpet pictures’, as a visual play on or echo of the carpets which cover tables and parapets in his portraits and sacred paintings; and it is satisfying, if unlikely, to imagine it in a much weightier form, to frame something like Gentile Bellini’s massive wall-sized scene of St Mark preaching in Alexandria, commissioned for the Scuola Grande di San Marco in Venice. In the latter case, this would have produced probably the earliest true example of an orientalist painting in an orientalist frame.

Hans Eworth (fl.1540-d.1574), Elizabeth I & the three goddesses, 1559, 62.9 x 84.4 cm, in its original frame. RCIN 403446

Another example of framemakers using these interlacings appears almost half a century later, on the original English oak frame of Hans Eworth’s allegorical portrait of Elizabeth I (1559), where the frieze is similarly enriched with a wide braid executed in mordant gilding. It indicates the reach and diffusion throughout Europe of pattern-books like Tagliente’s and Francesco di Pellegrino’s [11]: in this still relatively young medium of engraved illustrated books there was a much greater opportunity to broadcast very clear reproductions of complex motifs, and to broadcast them faster and more widely than ever before. This was so much the case that – like arabesques, grotesques, and all the classical scrolling and vertebrate candelabrum ornaments – a family of geometric patterns derived from Islamic examples became both extremely fashionable, and an inextricable element of the great soup of decorative possibilities available for all applied arts from the 15thcentury onwards.

Framing the Moroccan Ambassador

Generally, frames in England during the second half of the 16th and first third of the 17th centuries were likely to be simple profiles (architrave or entablature) which were painted black with parcel gilding, or occasionally given a polychrome finish – for example, in faux stone [12]. The interlacing on the Eworth frame (which is also inscribed at the bottom with a poem on Elizabeth’s conquest of the three goddesses, and would have had decorative bosses attached at the corners and centres) was evidently the mark of a fairly luxurious work, and so it is interesting to speculate on the original frame which would have been given to the portrait of the Moroccan ambassador to London, who arrived at Elizabeth’s court in 1600.

English School, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun (Moroccan ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I), 1600-01, o/oak panel, 113 x 87.6 cm., University of Birmingham

Like the portrait of Sultan Mehmet II by Gentile Bellini, 120 years earlier, the ambassador is painted as objectively as any Elizabethan courtier, emerging as a figure of brooding power and intelligence. The reason for his visit to London was to discuss an alliance against Spain, with the ultimate aim for the Moroccans of recapturing Andalusia from Spanish rule, and for the English of having a powerful ally against Philip III; also to discuss trade between Moroccan and England. In the portrait, the shoulder belt which supports the ambassador’s scimitar is decorated with gold thread in a pattern which would have been familiar in the circles of the court and its craftsmen, and it is very probable that a diplomatic portrait of this importance would have been given a frame of equivalent grandeur – possibly, therefore, decorated like the Eworth frame, with interlacings and arabesques echoing the sword belt.

Montage of English School, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, in the frame of Hans Eworth, Elizabeth I & the three goddesses

The painting seems to have passed into the possession of the Smith/ Smyth/ Smijth family of Essex, since in the 1820s it was sold out of the collection of Sir William Smith (1746-1823), of Hill Hall, Theydon Mount. Sir William’s ancestor had been a Sir Thomas Smith, who was Secretary of State to Elizabeth I, but sadly can have had nothing to do with the Moroccan ambassador, having died in 1577; this is a pity, as he was appropriately a polyglot, a professor of law, an MP, a dean, and English ambassador to France. His heirs were his younger brother and then his nephew, another Sir William Smith (1550-1626), Sheriff of Essex, who travelled with Sir Charles Cornwallis, the English ambassador to Spain, to negotiate a treaty between the two powers which would bring to an end their mutually warlike positions. The resulting treaty was signed in 1605, and it may be that Sir William was given the Moroccan ambassador’s portrait by the king as mark of royal esteem for his part in helping to bring about peace between England and Spain: this would have been a neatly circular response, given that the ambassador had visited Elizabeth I five years earlier in order to forge an alliance against Spain.

The portrait remained at Hill Hall until, as noted above, it was sold on or after the death of the later Sir William Smith in 1823. It was sold again in 1827 by the dealer Horatio Rodd, whose ‘Catalogue of Painted Portraits; comprising most of the Sovereigns of England… and many Distinguished Personages…’ noted that it had no frame at that point [13].

English School, Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, present frame and detail

The frame it has now is interesting in itself; it is probably later 19th-early 20th century, based on a revival of a 17th century style, and is also probably influenced by the last section (botanical drawings) of Owen Jones’s Grammar of ornament [14], or possibly by one of the later compendia of ornament which Jones inspired, such as Eugène Grasset’s La plante et ses applications ornementales [15]. It is decorated with acorns, and with what one would therefore expect to be oak leaves – save that these are like no oak leaves which have ever grown, being completely without lobes and growing in a fan shape. They are much more like chestnut leaves (both of which appear in Grasset and Jones), apart from the acorns, and suggest that the frame may perhaps be an apprentice or amateur piece. It has been cut down, altering the corner configurations, but must still be slightly too large for the portrait since quite a lot of the black inlay which bridges the gap can be seen at the sight edge. Sometime during the last quarter of the 19th and first half of the 20th century (the painting was acquired by the University of Birmingham in 1956), an imaginative collector or curator seems to have seen in this Arts & Crafts take on a 17th century British frame something which reminded them vaguely of date palms, perhaps, or almond trees, and in which they saw an ideal attributive companion for the portrait of the ambassador – an orientalist frame by adoption and propinquity.

Renaissance decoration: lacca da Venezia

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Louise de Rieux, 1525-50, o/panel, 16.5 x 12.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

Trade between Islamic and European countries remained very important during the 16th and 17th centuries; various goods continued to flow into Venice from every Moorish, Arabic or Ottoman city, and to diffuse their forms and patterns through Italian workshops. By the 1570s Venetian craftsmen were producing a range of furnishings and small classical aedicular frames decorated with lacca da Venezia, or Venetian lacquer, in which the surface arabesque decoration is derived from Islamic ornament. Similarly the sunk-panel work, which in the frames is inlaid with pieces of pietre dure, is taken from objects such as Persian bookbindings and other leatherwork. The frames in this style are best known through their use from the late 17th century onwards for the miniature portraits painted by the 16th century artist, Corneille de Lyon [16].

(Top) Venetian cabinet, late 16th / early 17th century, ebonized wood decorated with mordant gilding, inlaid with marble, lapis lazuli & mother-o’-pearl, 18 ½ x 20 x 14 ins (47 x 51 x 36 cm.), Sotheby’s, London, 29 October 2008, Lot 196; (left) Venetian cabinet, c.1570-80, ebonized wood decorated with mordant gilding, inlaid with coloured marble, 48 x 56 x 31 cm., Cambi Casa d’Aste, auction no 245, Lot 75, detail; (right) Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a lady, Sotheby’s, London, 3 July 2013, lacking pediment

Such frames, only around 40-45 cms tall overall, were probably made originally to contain small sacred paintings for use in a bedchamber or study, where they would be part of a suite of objects including cabinets (with architectural doors replicating the frames), jewellery caskets, looking-glasses on stands, book covers and even musical instruments. All these items were decorated with pietre dure inlays, sunk panelwork, and black lacquer covered in an all-over pattern of gold arabesques imitating, for example, Saracenic engraving (as in the hand glass shown with the length of Turkish silk, above), and painted tiles (below).

Turkish Iznik tile with floral, cloud-band and spiralling leaf design, c.1578, stonepaste and glazed polychrome, 25.1 x 24.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York

Venetian cabinet, Pandolfini, Florence; detail of column; Corneille de Lyon, Portrait of a man, National Gallery of Art, Washington; Louise de Rieux, Musée du Louvre; details of gilded spiralling leaves on the frames

These little frames, now all seemingly divorced from the small domestic altarpieces which they once held, might be considered as a class of Renaissance orientalizing frames, although their structure was classical and their proper contents sacred Christian subjects. Their orientalist aspect was limited to the motifs used in their surface decoration, and these were absorbed into the related arabesque ornament derived (and endlessly copied and adapted) from Nero’s Domus Aurea in Rome, which had been rediscovered in the 1480s.

Japanese Nanban frames

Flemish School, Holy Family with the young John the Baptist, early 17th century, o/copper, 23 x 28 cm., shrine overall 41.5 x 28 cm., wood and lacquer decorated in gold and silver, with gilt-copper fittings, Christie’s, 11 May 2015, Lot 2

Flemish School, Holy Family with the young John the Baptist, early 17th century, o/copper, 23 x 28 cm., shrine overall 41.5 x 28 cm., wood and lacquer decorated in gold and silver, with gilt-copper fittings, Christie’s, 11 May 2015, Lot 2

The Nanban shrine and moveable frame are a 16th century phenomenon created by the arrival in Japan of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, who, from the mid-16th century, set up churches which they needed to furnish, as well as exporting other pieces back home to generate some income. The paintings could be by European artists or by Japanese painters copying western models. The lacquer shrines or frames which held them, however, were local works of art especially made for the individual painting, but otherwise decorated in traditional style and materials, and with traditional motifs which had nothing to do with the Christian subjects they contained.

This subject is thoroughly discussed by Philippe Avila, in his article, ‘A Nanban painting and its frame, commissioned by the Jesuits in the Age of Exploration’, but it seems appropriate to add this brief note on it here, since the Nanban shrine with its sacred Christian painting is another expression, in another area of the world, of eastern influence upon western art.

Flemish School, Holy Family with the young John the Baptist, in Nanban shrine, closed

Framing 16th-18th century orientalist paintings

In spite of the earlier influence of Islamic ornament on mediaeval and Renaissance polyptychs and domestic altarpieces, the moveable frames around eastern or Muslim secular subjects were slow to change to reflect their contents. The curiosity and intense interest of artists such as Rubens in worlds different from their own were expressed through the depiction of decorative arts from those worlds – textiles, ceramics, costume, furniture, etc. – within the image, rather than in the setting outside and around that image. Pictures from the late 16th to 18th century of oriental subjects seem only to have been framed in the styles of the country and period of the artist, patron or collector, since they had to hang in interiors decorated in those styles. The frame functioned as part of those interiors – as an indigenous window frame looking out onto an exotic image.

Annibale Carracci (1560-1609), Portrait of a woman holding a clock, c.1580s, o/c, 60 x 39.5 cm., Louvre Abu Dhabi; reframed probably in the late 20th or the 21st century. Photo of frame: Nicholas Hall Gallery

One of the most striking works to emerge from this period is the fragment of a painting by Annibale Carracci, which has been cut down around the figure of a richly dressed African woman.

Giovanni Moroni (1520/24-79), The tailor, 1565-70, o/c, 99.5 x 77 cm., National Gallery

Jonathan Square in his essay on this painting notes a reference to the sitter as possibly a sempstress, ‘from the presence of pins and a needle stuck into her bodice’ [17]; she could therefore be a feminine version of Moroni’s almost contemporaneous tailor, who is dressed as

‘a successful, middle-class professional… a senior officer of a guild… or a cloth merchant’ [18].

There is nothing (save part of a sleeve and lace collar which stray into her space on the right-hand side) to suggest what kind of scene she could have been part of, with her direct gaze and symbolic-looking clock; perhaps a group portrait of higher-status court servants or merchants connected with a noble Bolognese family.

Bolognese school, Portrait of a gentleman, 16th century, o/c, 135.5 x 111cm. overall with frame, Harewood House

She shares her rich dress, emblems of occupation and somewhat ambivalent position with the 16th century portrait of a Bolognese gentleman in the collection of Harewood House, as well as with Moroni’s tailor; and it is probable that the original frame of the painting which she inhabited would have been appropriate for her costume and the clock she holds, as well as for her evidently equally well-dressed co-sitter – and almost certainly very similar to the Bolognese frame of the Harewood gentleman. This was an era when foreign ornaments and motifs were subsumed in the general decorative vocabulary, and it was unlikely that any attributive use of ornament would have been made to suit a frame to its contents, any more than that Carracci’s ‘Moorish woman’ would have worn different clothes from those worn around her in Parma or Bologna.

Rubens (1577-1640), Mulay Ahmad, Prince of Tunis, c.1609, o/panel, 99.7 x 71.5 cm., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in French Régence/early Louis XV style frame, applied by a later collector

Daily costume rather depended on how and where one made one’s life. In 1534, Jan Vermeyen, travelling with the armies of the Holy Roman Empire, painted the portrait of Mulay Ahmad, prince and later king of Tunis. The portrait has disappeared, leaving only Vermeyen’s engraving behind; however, more than seventy years later Rubens made a striking copy of the painting, which he kept in his studio and used as a model in paintings of the Magi. It appears, as far as it is possible to judge such things, that the model by Vermeyen must have been an honest and unpatronizing likeness of the prospective ruler of Tunis, shown against the Roman ruins which connected his world with that of the Netherlands in the 16th century, and suggesting that painter and prince were both descendants of the same far-reaching Roman empire.

Whilst in his studio Rubens’s copy (if it was framed at all) almost certainly hung in a plain stained wood or black and parcel-gilt cabinetmaker’s frame, like those in Frans Francken’s painting of Rockox’s house (with Rubens’s Samson and Delilah on the chimneypiece). After the artist’s death, however, it travelled from Flanders through collections in Britain and France, until in c.1904 it reached the US, having at some point in the intervening period been reframed in blithely inappropriate Régence style.

William Hoare of Bath (1707-92), Mrs Henry Hoare in a turban, c.1770-92, pastel/paper, 59.7 x 45.1 cm., Stourhead, National Trust,in original 18th century British Rococo pastel frame. Photo: David Cousins

This would be the practice throughout Europe for a couple of centuries. European sitters in eastern costume – or (more rarely) non-European sitters – were framed in contemporary local patterns, since their portraits would have to fit into interiors decorated in similar style. William Hoare’s portrait of his daughter, Mary (Mrs Henry Hoare), in a costume ‘à la Turque’ is framed in one of the characteristic British Rococo frames which can be found on other portraits by him [19].

Baroque frames like Hoare’s and like the Régence frame on the Rubens were also objects created from carved giltwood, relying on their sculptural form for their effect, so there was no room for the surface decoration of interlacings, knots and arabesques which had been such a feature of Renaissance frames.

Reynolds (1723-92), Omai, c.1776, o/c, 236 x 145.5cm., private collection, in ‘Maratta’ frame (almost certainly Reynolds’s original choice)

Reynolds (1723-92), Huang Ya Dong (Wang-Y-Tong), c.1776, o/c, 130 x 107 cm., Knole NT, in original ‘Maratta’ frame

Reynolds’s portraits of the young Polynesian, Omai or Mai, and the Chinese boy, Huang Ya Dong, were painted in costume – inaccurately, in the first case, and more authentically in the second – and framed in the ‘Maratta’ pattern he used frequently. They have two orders of ornament at the front and one on the back edge; Reynolds also used a more decorative version with added gadrooning on the top edge for his portrait of the 3rd Duke of Dorset at Knole, which was made by the London framemaker Thomas Vialls and cost twenty-five guineas [20]. The frame for the portrait of Huang Ya Dong was also made by Vialls, also for the Duke of Dorset (the sitter lived at Knole, acting as page to the Duke’s mistress), and cost £3.18.0 [21]; neither of these frames, nor any frames made for Hoare’s and Reynolds’s peers, attempted to harmonize in theme or ornament with the nature of the subjects they were holding.

It was not until the 19th century, when artists in greater numbers began to explore more adventurously (beyond the conventional boundaries which marked out the Grand Tour of their patrons), that the Mais and Huang Ya Dongs of later generations would be painted in their own settings, and the studies made by their portraitists of local architecture, woodwork and decoration would be used to design appropriate frames for them. The later 19th and early 20th centuries would see the introduction of the whole work of art in orientalist style, and a rapid growth in the production of both paintings and frames in this taste.

*********************************************************

[1] Jerrilynn Dodds, ed., Al-Andalus: the art of Islamic Spain, 1992, Metropolitan Museum, New York, p. xx

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.: see pp. xxv-xxviii for maps marking the change in Islamic/ Christian domination of the Iberian peninsular from 711 to 1492

[4] Although horseshoe arches were also a feature of classical and Visigoth architecture, their use in eg the Great Mosque of Cordobá gave them an especially Islamic flavour

[5] See Kaja Kollandsrud and Unn Plahter, ‘12th and 13th century polychromy at the northernmost edge of Europe: past analyses and future research’, Artigos, no 26, 2019

[6] See also the altar frontal from Berg in Sweden, now in the Statens Historiske Museum, Stockholm

[7] But see also Maria Vittoria Fontana, Islam and the West: Arabic inscriptions and pseudo inscriptions, 2020, Universitas Studiorum, Mantua, where Islamic influence is recorded ‘in Sicily and Southern Italy from at least the 11th century onwards’, and ditto, from the 15th to 17th centuries in a diffusion ‘from central to northern Italy’, p. 11. In this introductory summary, only three lines note eastern influence in the Veneto: ‘From the 12th century onwards parts of the façades of the palaces reflected in the Grand Canal in Venice display a particular eclecticism, in which Byzantium and Islam inspired the creativity of the Venetian masters’, p. 16

[8] See Stefano Carboni’s essay, ‘Islamic art and culture: the Venetian perspective’, Heilbrunn timeline of art history, Metropolitan Museum of Art

[9] Gary Schwartz, in ‘Convention and uniqueness in Rembrandt’s response to the east’, 13 September 2020, notes the trend for Italian and Netherlandish Renaissance painters to include oriental carpets in their work.This is also covered in Fontana, op. cit., pp. 19-22, remarking the number of eastern carpets, carpetty objects and textiles within paintings from the 13th century onwards, as well as ‘figures, sometimes with Asian or African physical characteristics, wearing “oriental” style clothing’, p.22.

The carpet in Bellini’s portrait of the sultan, however, is decorated with embroidery extremely close to the scrolling foliate patterns on the façade of the Ara Pacis in Rome (13-9 BC)

[10] Eileen Elizabeth Costello, ‘Knot(s) made by human hands: copying, invention, and intellect in the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer’, Athanor, XXIII, January 2002, p. 26. See also Stefano Carboni et al., ‘Venice’s principal Muslim trading partners: the Mamluks, the Ottomans, and the Safavids’, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: Essays, Metropolitan Museum of Art

[11] See ‘National Gallery, London: reframing Bellini’ for examples of and links to Francesco di Pellegrino’s 1530 book, La fleur de la science de Pourtraicture: Et Patrons de broderie.Façon arabique et ytalique

[12] Jacob Simon, The art of the picture frame, 1996, p. 17. From the remaining evidence, the fashions in framing changed very little during this period

[13] With grateful thanks to Jenny Lance, Curator of Art: Research and Cultural Collections at the University of Birmingham, for her help with the history and provenance of the portrait and her generous sharing of information and images

[14] Owen Jones, The grammar of ornament, first published 1856, ch. XX, ‘Leaves and flowers from nature’, pp. 153 ff

[15] Eugène Grasset’s La plante et ses applications ornementales, Paris, 1896

[16] For more on these small aedicular frames and on the suites of luxury Venetian objects to which they belonged, see ‘Corneille de Lyon: French portraits, Venetian frames, Islamic ornament’

[17] Joanathan Square, ‘A portrait that survives the test of time’, Nicholas Hall Art Journal, 25 June 2021. According to notes on the provenance of this painting on the website of art dealer Tomasso, ‘Cesare Locatelli (d. 1658), Bologna, mentioned in his 1658 inventory of assets [this painting] as “no. 110. Meza figura d’una mora […] et un horologgio in Mano” (half-figure of a black woman […] and a clock in her hand)…’

[18] From the National Gallery’s online catalogue entry (‘in-depth’)

[19] William Hoare, A nymph: Summer, c. 1759, Stourhead, and Frances Acland, Lady Hoare, c.1770-72, also Stourhead ; Alexander Pope, 1740, National Portrait Gallery; Mrs Thomas Giffard, pre-1764, Coughton Court; Mrs John Staples, pre-1771, Springhill, Co. Londonderry. These, or some of them, were almost certainly made by Isaac Gosset, Hoare’s framemaker in the 1760s and probably in other decades: see Jacob Simon, The art of the picture frame, 1996, p. 93, and for Isaac Gosset see The directory of British picture framemakers on the NPG website (also by Jacob Simon)

[20] Simon, ibid., p. 66; for Vialls see The directory…, op. cit.

[21] See Vialls as in note 20, and also ‘The Reynolds Room’ in Jacob Simon, ‘A guide to picture frames at Knole, Kent’