Corneille de Lyon: French portraits, Venetian frames, Islamic ornament

Maarten van ’t Klooster delves into the framing history of Corneille de Lyon’s small portraits of the French aristocracy, to try to discover when so many of them might have been matched with the decorative Italianate aedicules now so closely associated with them. This is followed by a short piece on the history of the frames themselves, by The Frame Blog.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Louise de Rieux, 1550, Musée du Louvre

At TEFAF in Maastricht last year (2018), two paintings by the Franco-Dutch artist Corneille de Lyon were offered for sale. Coincidentally, both were framed in a similar way: an aedicular style, complete with columns, an entablature with a frieze and cornice, and a pediment. A bit of research shows that many of the frames surrounding these small portraits painted by Corneille de Lyon (and also by his contemporaries) are made in a similar style, although they may be either genuinely antique or modern replicas. The large percentage of Corneille de Lyon paintings on the art market which are set in aedicular frames suggests two scenarios. On the one hand, there is the possibility that the original frames, or very early combinations of painting and frame, still survive; the other possibility is that art dealers, collectors or others involved in the sale or ownership of one of these portraits have decided to reframe it in this way.

This essay attempts to reassess the originality of these frames by taking a closer look at the current and historic framing of works by Corneille de Lyon, beginning with a brief description of the oeuvre of the painter and his life and milieu, in order to gain an idea of the dominant framing styles during and shortly after his life. Written sources concerning commissions are scarce in any period, and little direct information survives from the 16th century. The second part of the essay analyzes frames around paintings by Corneille in three important French collections, as well as a couple of examples from the United States. The selection of these collections is based on the rôle of an important 17th century collector. In conclusion, the pairing of the aedicular frame with Corneille paintings is further analyzed [1].

Corneille de Lyon and his milieu

Corneille de Lyon was probably born in The Hague around 1500-1510. He travelled to France in his twenties or thirties, settling in the city of Lyon in 1533, which resulted in his cognomen. Lyon, at the time, had a quartier teeming with Flemish painters such as Guillaume le Roy, Lievin van der Meer and Mathieu d’Anvers [2]. By at least 1544 he had been made painter to the Dauphin, since he made a formal request as such to be exempted from paying tax on his wine [3]. In 1547 he became a naturalized French citizen by royal decree, and he died in Lyon in 1575 [4]. His entire oeuvre consists of portraits, most of them on a small scale and with a single colour background. Stylistic comparison makes it feasible he was influenced by or had even trained with Joos van Cleve in the Flemish town of Bruges [5].

Corneille de Lyon(c.1500/10–d.1575), Catherine de’ Medici, c.1536, o/oak panel, 6.5 x 6 ins (16.5 x 15.2 cm.), Polesden Lacey, National Trust

The queen of France, Catherine de’ Medici (wife of Henri II: r.1547-59), owned a substantial collection of art, tapestries, furniture and pottery (including 300 portraits), and commissioned a number of works by Corneille, as well as sitting for him herself. After his death his reputation lingered for some time, diminishing over the following century, save with the rare collector who had a taste for portraits. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that his work was once more appreciated for its fine quality. The slackening in the demand for Corneille’s work may have had a profound impact on the frames corresponding with the portraits. In general, it can be stated that the chances of a painting having a surviving original frame are inversely proportional to the artist’s popularity. With this in mind, it might be possible that Corneille’s portraits survived the centuries without too many re-framings.

The aedicular frame

In George Bisacca’s article, ‘The rise of the all’ antica altarpiece frame’, he sets out the long history of the aedicule and the tabernacle frame. There has always been a close relationship between architecture and frames in general; and, as Bisacca points out, aedicular altarpiece frames had close ties to contemporary Renaissance architecture, which in turn drew on examples from classical antiquity. As architectural styles evolved during the 14th and 15th centuries, so did frame designs. Portraits by Corneille de Lyon are usually found in aedicular frames, most frequently of a very specific type.[6] These frames are almost always made from wood, with stone inlays, stone columns, and a faux-marbre finish and/or gilded decoration. The shape and style of the architectural elements differ in each frame, but in general, the triangular pediment is open, and sits on an entablature frieze which is inlaid with geometrically-cut pieces of decorative stone. The predella panel becomes another frieze with a band of inlaid stones.

Michelangelo (1475-1564), Porta Pia, Rome, 1561-65

Formally, as the name aedicule suggests, these frames closely resemble the façade of a classical temple; in this case as re-interpreted by Italian Mannerism. Similar re-interpretations of the vocabulary of classical architecture can be found in contemporary examples in Florence. During the 1520s, Michelangelo departed radically from classical precepts based on Vitruvius; otherwise seemingly irrational choices such as open or broken pediments, unconventional proportions, and exaggerated ornaments made his architecture and that of his followers stand out. Mannerist architecture developed simultaneously with the re-emergence of the art of pietre dure, a term which translates literally as ‘hard stone’, and which refers to the technique of inlaying shaped marbles and semi-precious gemstones into wood or other stone surfaces, to form sophisticated patterns or pictures; this technique was perfected in Florence, especially from the last part of the 16th century.

Giorgio Vasari (designer), Bernardino Porfirio da Leccio (creator), the Westminster table-top, made for Francis I de’ Medici, 1568-mid1577, Robilant + Voena

Coincidentally, an inlaid table-top designed by Giorgio Vasari could also be seen at the 2018 TEFAF in Maastricht, on the Robilant+Voena stand. This example demonstrates how pietre dure was applied to the most luxurious furniture, to create a highly decorative effect. The technical difficulties of executing such objects render them exclusive, grand-luxe, and very costly. Framing a portrait in a setting which uses this technique – even when greatly simplified – would be an indication of the status of portrait and sitter.

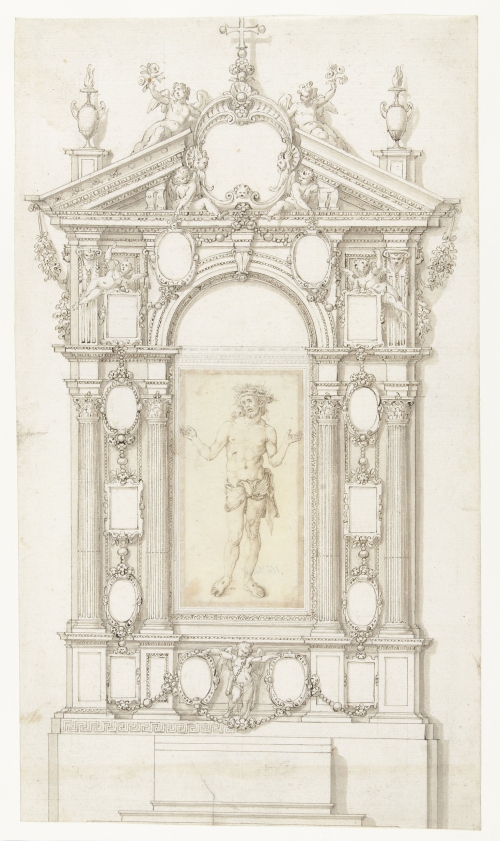

Girolamo Macchietti (after; 1535-92), drawing of an ornamental frame, 1545, paper, 38.8 x 22.3 cm., RP-T-1958-127, Rijksmuseum

As can be seen from prints and drawings from a period more or less contemporary with Corneille, the aedicular form was interpreted in less strictly classical terms than before the 1530s. In a drawing after Girolamo Macchietti in the Rijksmuseum, a much more ornate style has emerged. Although this type of drawing was probably never intended to be executed as a physical frame, the design and visual effects are very similar to those of the small aedicular frames found on works by Corneille. Macchietti worked for Giorgio Vasari on the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, for which he designed tapestries[7], and, as in the drawing above, tapestries often have elaborately designed borders, akin to frames in design and style.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-94), Christ in glory, c. 1492, pen & wash drawing; & Giorgio Vasari (1511-74), frame, pen & wash drawing, 25.3 x 27.1 cm., Albertina Inv. 511. Photo: © Albertina, Vienna

Two-dimensional borders of these kinds have an advantage over actual frames, since they are only limited by the imagination of the designer. It is tempting to suggest that a drawing such as the ornamental frame after Macchietti might have served a similar rôle, perhaps even to display another drawing or print – Vasari, for example, made similar use of architectural borders, creating them specifically for use with his own collection of drawings by other artists, such as for this Christ in glory by Ghirlandaio in the Albertina.

By the time that Corneille was working in Lyon and making a reputation for himself, the architectural style which had developed in central and northern Italy was spreading through Europe, partly via the School of Fontainebleau. François I of France had imported the Italian artists Rosso Fiorentino (from 1530 to 1540) and Francesco Primaticcio (from 1532 until c.1559) to work on the interior of the château de Fontainebleau, a project which was extremely influential in propagating the Mannerist style in France (it was François’s daughter-in-law, Catherine de’ Medici, who patronized Corneille de Lyon). Mannerist picture frames were one of the related developments; framemakers, like other furniture makers, used the same architectural forms, but could afford to take more liberties in the execution than builders could. Thus the context was ideal for generating a style of framing for these small portraits consistent with the patterns which have been associated with them for so long. However, it has not been clear until this point whether the aedicular frames associated with the Corneille portraits were made in France, or – as it turns out – were obtained from Italy. The jewel-like quality of the portraits must have influenced the choice of frame, underlining the preciousness of the picture; but a further question must then be, when was this choice made? – when were these particular frames chosen?.

The art market

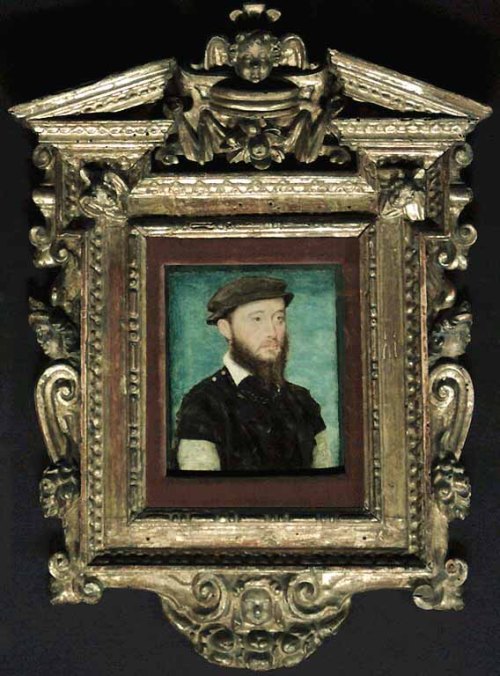

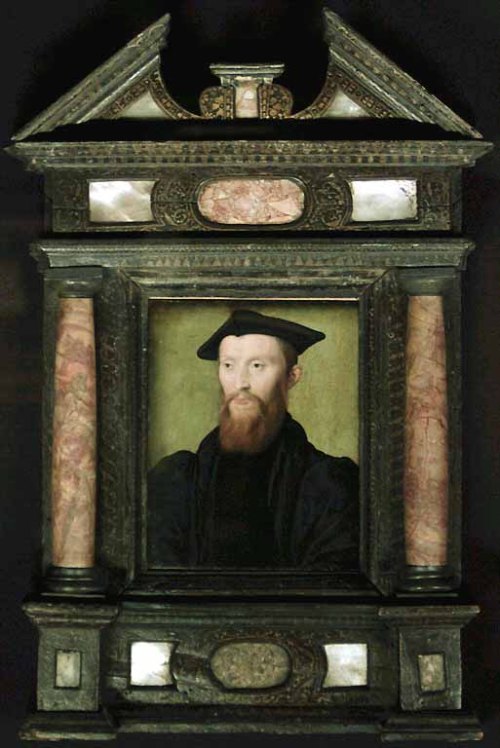

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), François, dauphin de France, o/panel, 15.4 x 13.5 cm., Haboldt & Co., TEFAF 2018

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait d’homme, probablement un officier royal, c.1545-50, o/panel, 7.1 x 6 ins (18.1 x 15.2 cm.), Richard Green

At the 2018 TEFAF in Maastricht, two works by Corneille de Lyon were on offer from two different dealers: one at Haboldt/Pictura in a replica frame (top), and one with the London art dealer Richard Green (above). The Amsterdam art dealer Bruil & Brandsma showed the very same Corneille painting from Habold/Pictura at PAN Amsterdam (also in 2018), in the same aedicular frame. This example is inlaid with mother-o’-pearl and has wooden columns; it seems to have been paired with the painting for some time. The execution and the choice of materials makes it likely to be a 19th or early 20th century replica, although it is possible that antique elements may form part of it.

The second portrait at Richard Green, arguably the better of the two, has – like the other – an aedicular frame, and closer inspection reveals that this frame is not antique either. Although it is superficially very much in the style of an authentic frame, with inlaid panels of marble, lapis lazuli and mother-o’-pearl, the flanking columns are of wood with a faux-marbre finish, rather than stone, and their turned bases lack the refinement of the authentic versions – as does the gilded decoration. It also lacks the open triangular pediment of one of the genuine Mannerist frames.

Corneille de Lyon, Portrait d’homme, probablement un officier royal, c.1545-50, Sotheby’s, Paris, 27 June 2013, Lot 33

The recent provenance confirms that the current frame could not in any case be the original, since, when it was sold in 2013, the portrait had a 17th century French Mannerist giltwood frame, with cherubs at the corners (and probably therefore intended for a sacred image). It had been in a private Flemish collection for several generations, and may have been reframed in this way during the late 19th or early 20th century. The switch to a so-called ‘Corneille de Lyon’ frame in the latter case, and the other frame on the Haboldt & Co. portrait, provide an index of how the art market (and many art historians) now expect his work to be framed, in an apparently ‘authentic’ coupling.

Corneille de Lyon at the Musée Condé

A view of the Clouet Room in the Musée Condé, Chantilly; the Corneille de Lyons are the smaller portraits. Photo courtesy of the Musée Condé

One museum with a relatively large collection of works by Corneille is the Musée Condé in the château de Chantilly. The history of this group is one of private collectors, rather than a larger state collection; the Musée Condé was established after Henri d’Orleans bequeathed his château and its contents to the Institut de France. Because most of the paintings in the museum have changed owners several times, each frame is very likely to have been changed as well – perhaps more than once.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Gabriele de Rochechouart, dame de Lansac, Musée Condé

A quick survey of the nine Corneille paintings as they are displayed in the museum indicates that that has indeed been the case; none of the frames seems to date back to the 16th century [8]. The current settings of the portraits of Marguerite de France, Gabrielle de Rochechouart, A lady presumed to be Gabrielle de Rochechouart and the Portrait of a lady are gilded, Baroque or 19th century frames in Louis XIII-style and Louis XIV-style.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Le dauphin François, Musée Condé

The portraits of Le dauphin François and Jean de Taix are framed in dark wooden moulding frames, with little or no ornamentation, which also seem more likely to date from the 19th century. La baillive de Caen has a narrow frame with very little decoration, which is possibly 18th century. This portrait has been previously attributed to Corneille, but it is based on a drawing made by Jean Clouet, who was working in Paris at the time.[9]

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Hercule-François de France, duc d’Alençon, Musée Condé

Corneille de Lyon(c.1500/10–d.1575), Catherine de’ Medici, c.1536, o/oak panel, 6.5 x 6 ins (16.5 x 15.2 cm.), Polesden Lacey, National Trust

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Catherine de’ Medici, Musée Condé

The portrait of Catherine de’ Medici – a copy after the original in Polesden Lacey, which has a miniaturized Mannerist revival-style parcel-gilt tabernacle frame – is set in a reverse tortoiseshell frame, and the portrait known as the duc d’Alençon (which has been rejected as a work by Corneille in the catalogue raisonné) has another reverse design with bold floral ornament on an ebony or ebonized ground. Both these frames – like the Polesden Lacey frame – almost certainly date from the 19th. Most of the nine portraits in the Musée Condé have been in its collection since the 1870s. What is particularly striking is that none of them has either an aedicular frame, or a setting more or less contemporary with the artist. Whereas a number of more recently-fitted frames on portraits by Corneille have been in the replica aedicular style, imitating the antique, the Musée Condé portraits all have symmetrical, rectilinear frames.

Since several portraits from the museum belonged to François-Roger de Gaignières (1642-1715), the inventories of his collection are obviously of prime importance in shedding light on the history of the frames of these particular works. The portrait of the dauphin François, for example – inventory number 457 – is listed as having no frame [10]. The portrait of the dauphin which was on show with the dealers Haboldt (and also with Bruil & Brandsma) has a 19th century annotation on the verso of the frame, stating that it too came from the collection of Gaignières [11]. Besides the Musée Condé portrait, the dauphin was represented in two other versions in the inventory of Gaignières, of which only one does not rule out identification with the Haboldt picture. This was set in a gilt frame [12].

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Marguerite de France, Musée Condé

Back in the Musée Condé, two portraits of a Marguerite de France appear in the inventory, both of which entered the collection of the Musée Condé: one depicts the duchess of Berry, the other the queen of Navarre (confusingly, both ladies were referred to as Marguerite de France). Both paintings had gilt frames [13]. Two portraits of Gabrielle de Rochechouart are also mentioned in the inventory, but whilst the Musée Condé owns two portraits of her, there is no evidence in this case to confirm that the second one ever belonged to Gaignières. The painting which can be identified with an entry in the inventory had a gilt frame, and in the other entry there is no mention of a frame [14]. Only one other painting from the Musée Condé is to be found in the Gaignières collection; this is of the duc d’Alençon, whose portrait appears several times in the inventory. All the versions mentioned there have gilt frames [15]. The black and floral frame on the version in the Musée Condé certainly does not accord with this, and must date from around 150 years after the inventory was made.

Corneille de Lyon in the Louvre

There are twelve portraits by Corneille de Lyon in the collection of the Musée du Louvre, and these are framed in various styles.

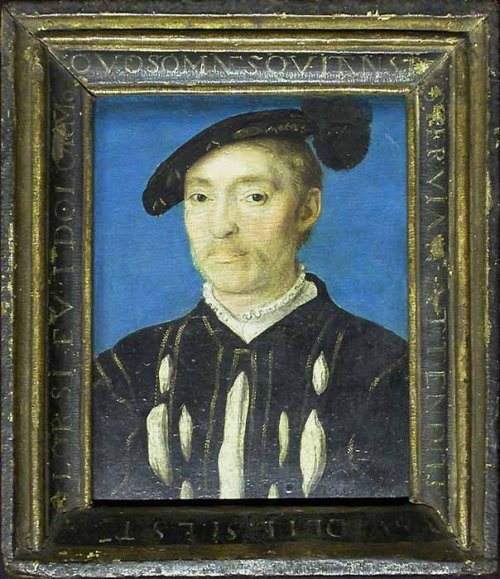

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait d’homme, dit autrefois François de Voisins, chevalier d’Ambre, 16.5 cm x 13.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

One of the frames, on Portrait of a man (previously thought to be François de Voisins; Groër, fig. 7), is noted on the Joconde site as being antique [16]. However, it is clearly not original to the portrait as it is a rainsill frame from a sacred image, and one which has been reduced to fit its current occupant. The inscription in the hollow and on the sill, which has lost elements at the corners, would formerly have read, ‘O vos omnes, qui transitis per viam: attendite et videte, si est dolor sicut dolor meus’, which translates as ‘O all ye that pass by the way, attend and see if there be any sorrow like to my sorrow’ [17]. This text was used in the 16th century at Easter as a sung part of the liturgy on Holy Saturday, and is associated with paintings of the Virgin as the Mater Dolorosa; the frame is therefore more or less contemporary with the portrait, but is completely out of key with its debonair courtliness.

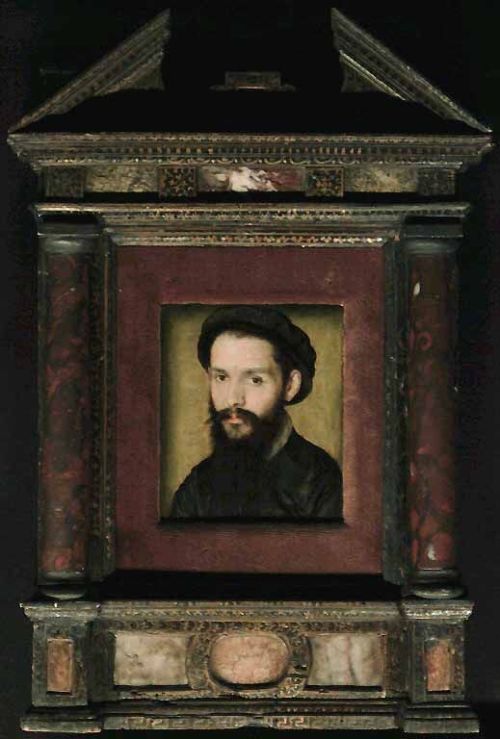

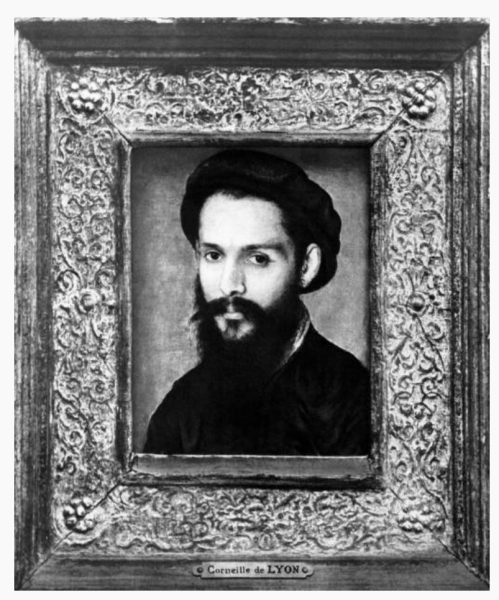

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait présumé de Clément Marot, 1496-1544, in aedicular frame (above) & cassetta with pastiglia ornament (below), Musée du Louvre

Another painting with an antique frame is the Portrait of a man, presumed to be Clément Marot (Groër, fig. 71; given to the Louvre in 1949). This is in one of the characteristic wooden aedicules, inlaid with stone panels, with genuine stone columns, and with gilt and painted decoration. It’s in relatively good condition, despite some damage to the wood; however, it has been given a wide velvet-covered inlay to fit it to the painting, which again indicates that this is a marriage of convenience for two disparate works of art. There is in any case a black-&-white photo of this portrait in a cassetta with pastiglia decoration on the frieze, taken at some previous stage in its existence; this, too, seems to have been given an inlay behind the sight edge at the bottom in order to accommodate the painting. It would be nice to think that this earlier frame may be a rare and vanished glimpse of a framing which dates from the 16th century, but the inlay unfortunately precludes this possibility. Other works by Corneille in aedicular frames have also been given inlays to fit portrait to sight contour; these are usually of painted wood mimicking the main structure, but they tend to be much narrower.

Most of the paintings in the collection of the Louvre were only acquired during the late 19th or early 20th centuries; several were previously owned by the same Roger de Gaignières whose works by Corneille de Lyon also entered the Musée Condé [18]. All the Louvre paintings from the Gaignières collection have aedicular frames save one (Groër, figs. 46A, 47, 83, 101, 116). The only one not framed in this way was noted in the 1711 inventory as having a gilt frame [19]. Although almost thirty paintings in the catalogue raisonné are mentioned as having belonged to the Gaignières collection, only seven are confirmed as having indisputably formed part of it [20]; Groër lists their entries in the inventory:

- Two small paintings of Mary and of a woman, by Corneille, without frame

- François, Dauphin of France, by Corneille, without frame

- Two x François de Scepeaux, marshal of Vieuveille, gilt frame, Corneille

- Blaise de Montluc, marshal of France, Corneille

- Charles de la Rochefoucauld, count of Randan, without frame, Corneille[21]

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Charles de La Rochefoucauld, comte de Randan (1523 – 1562), Musée du Louvre

The last in this group of paintings can be identified with a portrait (above) in the Louvre (acquired in 1961). In the inventory it is noted as having no frame, and is now displayed in an aedicular frame, which must therefore have been added after 1715 [22].

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Jean de Bourbon Vendôme, Comte de Soissons (1528to57), c.1550, o/c, 19 x 15.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

The portrait of Jean de Bourbon which appears as number 78 on the inventory list is listed there as having a gilt frame; it is now framed in a miniature giltwood Mannerist tabernacle with another velvet inlay bridging the gap between sight edge and painting [23].

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Jean de Brosse, duc d’Étampes, c. 1535-45, 16 x 13.5 cm., Musée du Louvre

A further portrait by Corneille in the Louvre collection, of Jean de Brosse, duke of Étampes, can be identified as number 170 in the inventory: Jean de Bretagne, duc d’Etampes, described as having a gilt frame in the early 18th century, but now again in one of the characteristic ‘Corneille de Lyon’ aedicular frames. It entered the collection of the Louvre in 1817.

Corneille de Lyon in Versailles

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Françoise de Longvy, dame de Brion, c.1535-45, o/ panel. 16 x 13 cm., Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon

The third museum to own a substantial portion of the Gaignières collection is the château de Versailles. Its portrait of Françoise de Longvy can be identified in the Gaignières inventory, recorded once more as in a gilt frame [24]. This portrait is currently set in an aedicular frame which originates from a different source from the others, or might possibly be a 20th century reproduction; it lacks any of the finely-gilded overall decoration found on most of the others.

Further Versailles miniatures can be identified in the inventory: the Portrait of Suzanne d’Escars, dame de Pompadour, in a gilt frame [25], and – rather less certainly, through confusion with her husband’s first wife – the Portrait of Anne-Jacqueline de la Queille, lady of Aubigny, which may be ‘Anne Stüart, mareschal d’Aubigny’, also in a gilt frame [26]. Another image of Marguerite de France is listed amongst the Versailles portraits, although it is not officially recorded as coming from the collection of Gaignières.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Jeanne de Halluin, Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. No image of the frame is available

There are two contenders in the inventory to be the Portrait of Louise de Halluin, one with a gilt frame, the other without mention of a frame [27], whilst Jeanne de Halluin, lady of Alluye, appears once, in a gilt frame. The portraits of Béatrix Pacheco d’Ascalona, Philippe Chabot and René d’Amoncourt are also listed as having gilt frames [28].

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Madeleine de Valois, Musée national des châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon. No image of the frame is available

The Portrait of Madeleine de France (the queen of Scotland) has not been identified with certainty; her portrait may have been confused with that of the second wife of James V, Mary of Guise [29].

In more general terms the Gaignières inventory offers a glimpse into the rest of the Gaignières collection. The combined inventories of 1711 and 1717 show that nearly half the collection was set in giltwood frames [30]. Sixty-seven of the 987 paintings are listed sans bordure – having no frame at all; another twenty-three paintings have various settings, including ebony frames and boxes (in the case of miniatures). In the case of the last identifiable group of 411 paintings, there is no mention made of any frames. Amongst all these different categories, it seems highly unlikely that, if an aedicular frame existed on one or more of the portraits, the inventory-maker would have neglected to record the fact.

Other collections

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a man, identified as Anne de Montmorency, 1533 or 1536, o/panel, 6 ½ x 5 ¼ ins (16.5 x 13.3 cm.), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts owns three paintings by Corneille, one of which is considered to be by the artist himself, one is attributed to him, and one is from his circle. The portrait considered genuine (Groër fig. 10; above) is framed in a Mannerist-style aedicule which has been fitted to the portrait with a narrow gilt inlay; it may contain authentic elements, but the ornament on the friezes of the inner frame, the entablature and the predella panel is all on a very large scale relative to the refinement of detail in the painting.

Corneille de Lyon (circle of; c.1500/10–d.1575), Françoise de Longwy, c.1527, 5 ¾ x 4 5/8 ins (14.6 x 11.7cm.); the framed portrait in a case in the Kunstkammer, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The frame around the portrait of Françoise de Longvy may be antique, or a good quality reproduction. The small image available suggests the frame has stone columns and pietre dure inlay on the entablature and predella panels.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a man, o/walnut panel, 6 ½ x 5 5/8 ins (16.5 x 14.3 cm.), National Gallery of Art, Washington

The National Gallery of Art in Washington owns one portrait by Corneille in an aedicular frame (above). This appears to be antique – at least elements of it may be: it may have been given a new sight edge and a new base.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, there are numerous works by, attributed to or associated with Corneille de Lyon.

Corneille de Lyon (attrib.; c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a bearded man in black, o/panel, 17.1 x15.9 cm., Metropolitan Museum, New York. Photo: with thanks to Paul Jeromack

The Portrait of a bearded man in black is framed in an idiosyncratic Mannerist revival style; parcel-gilt, with scrolling clasps across the frames at corners and centres [31]. This portrait was for a long time attributed to Holbein, originally by Horace Walpole; it very probably formed part of his collection of miniatures at Strawberry Hill House, along with work by Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver, until sold in 1842. The frame was evidently made for the painting, in what would have been considered an appropriately ‘Tudoresque’ style in the 19th century.

Corneille de Lyon (attrib.; c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a man with a black plumed hat, c.1535-40, o/panel, 7 x 5 ½ ins (17.8 x 14 cm.), Metropolitan Museum, New York. Photo: with thanks to Paul Jeromack

The Portrait of a man with a black-plumed hat is another piece from the Gaignières collection, so can be assumed either to have been unframed, or to have had the ubiquitous and unelaborated ‘gilt frame’ [32]. It now has a small, attractively proportioned and decorated Baroque version of a cassetta, with delicate arabesques on the frieze. Having passed through various royal collections after being leaving the Gaignières collection in 1711, it might have been reframed at any point, including during the first half of the 20th century when it was in the collection of Jules Bache. In the case of these portraits by Corneille de Lyon, it seems almost that the more authentic the frames appear, the less likely they are to be original.

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a man with gloves, c.1535, o/panel, 8 3/8 x 6 ½ in. (21.3 x 16.5 cm.), Metropolitan Museum, New York. Photo: with thanks to Paul Jeromack

This painting, however, makes no pretence of being framed in a style ascribed to the era of the artist; instead it is set in a Baroque Roman frame, as if the portrait of an Italian noble, or part of that noble’s collection. Evidently reduced from a larger frame, the moulding is wide for the portrait, and the ornament out of scale; apart from this, the style is strangely suited to the pose and costume of the sitter.

The Portrait of Charles de Cossé was also previously in the Gaignières collection, with no mention of the frame [33].

Framed by association

Significant numbers of these small court portraits by Corneille de Lyon are currently set in aedicular frames; so much so, that this very specific type of frame – with stone columns, inlaid stone panels and overall fine mordant gilded decoration on a black ground – is now closely associated with his work. Nearly all of the portraits from his hand in the Louvre, for example, have such frames, and it is possible that this large group provided sufficient evidence for art dealers and museum curators to assume that the style was the authentic design for framing his portraits. The fact that not all the Corneille de Lyon paintings in the Musée Condé have similar frames raises precisely this question of authenticity. Through the inventory of the Gaignières collection, it can be concluded that at least some of the works in the Louvre have been given aedicular frames since 1717, and, given the fact that other portraits in the collection are also framed in this way, it is likely that these frames were added by the museum.

As for the aedicular frames around works in private hands, there may be two explanations – the first, that there are actually Corneille de Lyon paintings which were framed in the aedicular style during his lifetime or shortly afterwards; the second, that collectors, dealers and auction houses reframe works by Corneille in this way because not only are his portraits set in these little aedicules an aesthetically pleasing combination, but the apparent evidence of the collection in the Musée du Louvre gives credibility to this choice of frame.

However, no concrete evidence has so far been discovered which indicates that any of Corneille de Lyon’s portraits were originally displayed in these frames. Such a style of framing would certainly not be out of step with the Italianate taste of the French court during the reigns of François I and Henri II; Mannerist furniture with semi-precious stone inlays was made both during and after Corneille’s lifetime, and, since the frames are almost contemporaneous with the portraits, it is not completely impossible that they might have been combined; they were evidently both grand-luxe objects. Further research is required to ascertain whether any of his paintings were in fact ever housed in this fashion. The greatest caveat in this respect is that a frame made in the style of a small portable altarpiece would almost certainly have been considered unsuitable at the time for framing a secular painting.

The number of Corneille de Lyon paintings now set in aedicular frames is evidently sizeable. The inventory of François-Roger de Gaignières’s collection provides a valuable insight into the framing history of roughly 10-12% of the entire surviving body of work, and none of them is noted as having a remarkable frame. If this were extrapolated to the other 90%, we would expect to find very few such precious and decorative designs, a deduction which is supported by the evidence of all the aedicular frames which have been given inlays of various kinds and sizes to fit them to the portraits they now hold. Beginning at some point in the 19th century (less probably, in the 18th) these frames began to be used for Corneille’s paintings – possibly by a single collector – and eventually, perhaps through the group of these framed portraits in the Louvre, the style became indissolubly connected with his work. A similar marriage of a school of paintings and a type of frame would happen later, when Impressionist works were reframed by dealers in antique French Baroque patterns. The most probable conclusion therefore is that, despite the visually appealing combination, most (if not all) of the aedicular frames seen today on work by Corneille de Lyon are not original, and were added at a later date.

*******************************************

Maarten van ‘t Klooster studied art history at VU University in Amsterdam and graduated the Master of Curatorial Studies at VU University and University of Amsterdam. He has a particular interest in nineteenth century art and picture frames. He is a regular guest speaker on picture frames on the Master’s course Art, Market and Connoisseurship at VU University.

*******************************************

Corneille de Lyon: the Italianate aedicules: The Frame Blog

Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a lady (said to be Marie de Batarny), o/panel, 7 5/8 x 5 ¾ ins (19.4 x 14.7 cm.), Sotheby’s, London, 3 July 2013, Lot 4

The small aedicular frames found on so many portraits by Corneille de Lyon – and also occasionally on work by the Clouets, père et fils – may have been subsequent reframings, as Maarten van ’t Klooster has so clearly established, but what are they, and where did they come from?

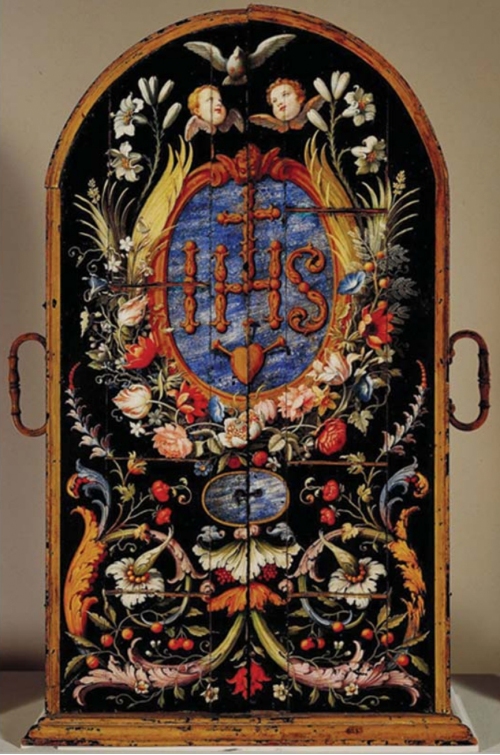

These very distinctive objects, generally – if inaccurately – called ‘Corneille de Lyon’ frames, turn out to be members of a family of ebonized Venetian lacquerware (lacca da Venezia), inlaid with panels of marble and semi-precious stones, and dating from the 1570s to the early 17th century. Such pieces display a range of influences, which may include Flemish construction, large-scale 16th century Venetian stone altarpieces, and pietre-dure decoration, according to various sources; the major and unquestioned influence is, however, Islamic ornament and finish. This is evident in the so-called ‘sunk-panel’ work, where laminated strata are cut out in cusped and ogee-edged ‘Moorish’ shapes to hold the inlays, and in the delicate arabesques of the surface decoration. They include a number of splendidly enriched cabinets, which are miniaturized – less than two feet high – and are made to stand upon tables or desks (they have often had feet added later); they were probably intended to hold writing equipment.

Venetian cabinet, late 16th / early 17th century, ebonized wood decorated with mordant gilding, inlaid with marble, lapis lazuli & mother-o’-pearl, 18 ½ x 20 x 14 ins (47 x 51 x 36 cm.), Sotheby’s, London, 29 October 2008, Lot 196

Venetian cabinet, detail, Sotheby’s, 29 October 2008; Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of Mellin de Saint-Gelais (1491 – 1558), Bibliothécaire du roi à Fontainebleau, c.1545-1550, 16 x 14 cm., Musée du Louvre

If the frames can be described as aedicules, then the cabinets comprise whole classical temple façades, often in a tripartite form, with a central architectural niche. The example above has as its central section what is to all intents and purposes – with its two columns supporting an open triangular pediment – a classical structure identical to one of the aedicular frames found on Corneille de Lyon portraits, enclosing two drawers rather than a painting, and unexpectedly imported wholesale onto the front of a small cabinet.

Venetian cabinet, c.1570-80, ebonized wood decorated with mordant gilding, inlaid with coloured marble, 48 x 56 x 31 cm., Cambi Casa d’Aste, auction no 245, Lot 75

Venetian cabinet, detail, Cambi d’Aste 245; Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a lady, Sotheby’s, London, 3 July 2013

Venetian cabinet, detail, Cambi d’Aste 245; Corneille de Lyon (c.1500/10–d.1575), Portrait of a lady, Sotheby’s, London, 3 July 2013

Both these cabinets are striking examples of the genre, being so close in construction and finish to the frames, especially in their central niches – from the open pediment with its plinth for a statuette, and wooden salomonic or marble columns, to the entablature and predella with inlaid panels of stone, and the intricate mordant gilding on a black ground. The fact that they are generally dated from the 1570s onwards, or from around the time of Corneille de Lyon’s death, is another indication that the paintings they now frequently contain can never have been originally envisaged as having these aedicular frames.

Venetian cabinet, 16th century, ebonized wood decorated with inlaid painted medallions of mother-o’-pearl & mordant gilding, 30 x 35 x 26 cm., Pandolfini, Florence, 19 November 2015, Lot 44

The cabinet above has a drop-down front flap, which may double as a writing slope, indicating that such pieces were definitely desk-like in their functions; precious objects holding often luxurious implements for the use of the more prosperous classes.

Venetian cabinet, Pandolfini, Florence; detail of column; Corneille de Lyon, Portrait of a man, National Gallery of Art, Washington; Louise de Rieux, Musée du Louvre; details of gilded spiralling leaves on the frames between the sight edge & the columns

This particular example of the Venetian cabinets is interesting for the decoration of the four columns (which are wooden rather than stone) with delicate spiralling ferns, which are often found on the aedicular frames, gilded on the flat friezes behind the columns. Repetitive running and overall ornaments of this type, often foliate and floral, are characteristic of lacca da Venezia and derive from the objets d’art of all kinds, decorated with Islamic ornament, which flowed through Venice from the 13th to the early 17th century.

Gentile Bellini (follower of; 1429-1507), Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, c.1510, o/panel, 21 x 16 cm., Museum of Islamic Art, Dohar

Venice was, as it were, the central clearing-house of Europe for Christian pilgrims going to Jerusalem and Muslim pilgrims travelling to Mecca, and the auxiliary effect of this traffic was a great deal of commerce in both directions.

Mahmud al-Kurdi, ‘Veneto-Saracenic’ Persian (Mamluk dynasty) lidded bowl, brass inlaid with silver arabesques, 15th to 16th century, 10 cm. high x 14.7 cm. diam., British Museum

As well as a clearing-house, Venice was a giant warehouse, through which passed silk, embossed leather, Saracenic metalwork alla damschina (such as the bowl above), carpets, linen, crystal, velvets, precious and semi-precious stones [34]. Respecting such items used in Italian homes for devotional purposes,

‘…Islamic craftsmanship and ornament seemed to confer biblical “authenticity” because of the origin of such articles in the Holy Land. Similarly, inlaid metalwork… invested the devotional aedicule or table with connotations of biblical lands’ [35].

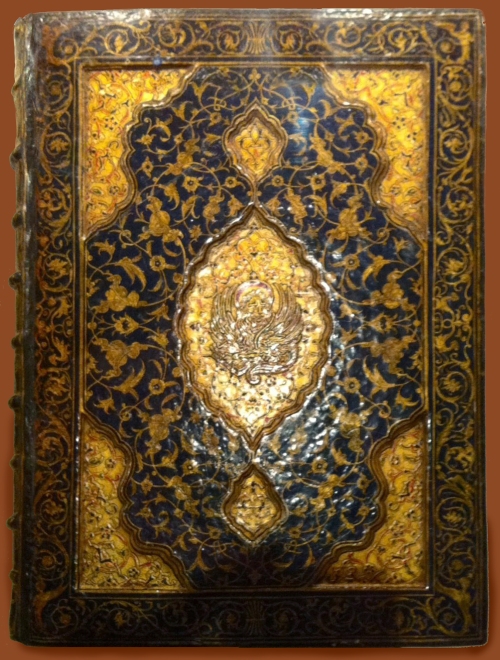

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 had opened the doors to a growing flood of trade, and Venice had grown richer and more powerful, fuelled by this commerce between Islam and western Europe. Venetian publishers even produced the first printed version of the Qur’an for their Islamic clients, and bookbindings influenced by Turkish and Persian examples (made for manuscripts) were copied in embossed leather and then in lacquer.

Leather bookbinding, Persia, 16th century, decorated with gilded filigreework, 64.3 x 35.7 cm., Sotheby’s, London, 6 April 2011, Lot 186; the envelope format is explained by the contents being produced as a manuscript of detached pages

Leather bookbinding, Persia, 16th century, decorated with gilded filigreework, 64.3 x 35.7 cm., Sotheby’s, London, 6 April 2011, Lot 186; the envelope format is explained by the contents being produced as a manuscript of detached pages

Lacquered book binding, Venice, 16th century, sunk-panel work based on Islamic patterns, polychromy & mordant gilding, from the collection of Francesco Priuli (1570-1610), Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon

Venetian lacquerwork of this kind began to develop before the 1550s, and fell out of fashion after the 1620s; as well as small table cabinets it decorated bookbindings, like the example above, and looking-glass and portable altarpiece frames. Even small pieces of furniture, such as a spinet in the collection of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs and (more distantly) a harpsichord in the V & A, were lavished with similar lustrous black and gold patterns.

Venetian casket, 16th century, c. 1575, ebonized wood, mother-o’-pearl inlay & mordant gilding, Christie’s, 2018

Venetian casket, 16th century, c. 1575, ebonized wood, mother-o’-pearl inlay & mordant gilding, Christie’s, 2018

Titian (after; fl. c.1506- d. 1576), The artist’s daughter Lavinia with a casket (original, private collection); coloured lithograph after an engraving by James Heath (published 1795-1815)

This figure, said to be of Titian’s daughter, shows her holding a Venetian casket similar to the one shown immediately above her, enriched with rock crystal. These shaped boxes might include looking-glasses, and were intended as toilet boxes or jewellery caskets; they were the essence of luxury, and the pose of the girl in the painting in her slashed velvet costume and pearls emphasizes the grand-luxe nature of such an object – the feminine equivalent of the writing cabinets.

The decorative lacquer with which this and all related objects were finished was based on shellac, made from ‘a resinous incrustation produced on certain trees’ by the resin of the lac beetle, and imported from India and its neighbours where it was ‘used as sealing wax, dye and varnish’ [36]. Lacquerware came into Europe from the 14th century, but remained a rare and generally unknown substance until the 16th century, when

‘the type of lacquer called “Coromandel” was imported into Europe, principally by Venice’[37]

This was influential enough to catalyze the production of home-grown lacquer…

‘…in the 16th century Venetian artisans began to make boxes, cabinets, frames and caskets that were varnished with Indian shellac in red, black, or dark green in imitation of Eastern lacquerware…In 1515 Leonardo, as a reminder to himself, wrote this note: “Learn how to melt gum into lacquer-varnish”.’ [38]

However, the processes were so unfamiliar in the west that,

‘Europeans could not match the perfection of the Oriental lacquers. It was not until the late 17th century that the secret of the “art of Japanning” became known to Europe’ [39].

Commission of the Doge Nicolò Da Ponte to Marc’Antonio Contarini, as Podestà of Vicenza; Venice, 1582. Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice (BNM); It. VII, 1869 (= 8134); leather over sunk-panel carved pasteboard, finished with gilding, paint & lacquer, 23.2 x 16 cm. Photo: © Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice

The book cover above is finished with

‘…an overall gilding : gold leaf was applied over the entire leather, becoming the background for the detailed pictorial decoration. Persian and Ottoman elements like arabesque branches and thin buds are brightly painted with black ink onto this gilded ground and filled with red and green colours. The composition is symmetrically embellished by a thick coloured layer applied over the gold leaf with the creation of a relief effect in some areas: this additional paste surface is also fully adorned by sinuous flowers painted with golden and black inks.

A layer of varnish applied by brush covers the entire surface: this is the reason why this type of binding is called “lacquered” like its Islamic models’ [40].

These books and their opulent bindings were precious objects, printed and covered to take their places in the library of a connoisseur (the example from the Gulbenkian was in the collection of Francesco Priuli, Venetian ambassador to the Duke of Savoy, to Spain, and then to the court of Bohemia [41]). The technique thus naturally came to be applied to similarly luxurious goods; not only to jewel caskets and writing cabinets, but to looking-glass frames. Glass was as costly as jewellery – perhaps more so – and it was the craftsmen of Murano in Venice who created the earliest, most transparent glass, flat rather than convex (as mediaeval glass was), and silvered with tin and mercury on the back to produce the clearest reflection. Because mirrored glass was so expensive, looking-glasses remained relatively small until the late 17th century.

Venetian looking-glass frame & stand, c.1590s; carved wooden frame & sunk-panel stand, inlaid with mother-o’-pearl, finished with paint, lacquer & mordant gilding; replacement mirrored glass; 58.5 x 31.5 x 12.5 cm., © Victoria and Albert Museum

This looking-glass and stand is less than two feet high overall, and would probably have formed part of a suite of matching table furnishings with a toilet casket, and perhaps a jewellery casket as well. It was made with a sliding shutter to protect the costly mirrored glass (both subsequently lost and now replaced by modern replicas), just as the more valuable paintings in a collection of the period might be concealed behind sliding panels or curtains [42]. It has many points of similarity with the aedicular ‘Corneille de Lyons’ frames – the lacquered finish, polychromy and mordant gilding; the sunk-panels, inlay, and arabesque decoration – whilst being utterly unlike them at first glance: lighter, more playful, curvaceous and feminine.

Venetian looking-glass frame, late 16th-early 17th century, carved wood & sunk-panel with open pediment, inlaid with mother-o’-pearl, finished with paint, lacquer & mordant gilding; replacement mirrored glass; 21 ¼ x 17 ins (54 x 43 cm.), Christie’s, New York, 23-24 April 2013, Lot 314

The second looking-glass frame may actually have been designed as the frame for a painting, and may therefore have a closer link than other pieces of lacca da Venezia with the aedicular frames. Here there is also another influence visible – that of the Venetian Mannerist ‘Sansovino’ frame (another style named after an artist who has nothing to do with its design).

Unknown artist, Christ preaching, carved, polychrome & parcel-gilt ‘Sansovino’ frame, Museo Civico, Palazzo Consoli, Gubbio. Photo: Peter Schade

Venetian looking-glass frame, Christie’s; & ‘Sansovino’ frame of Christ preaching; comparative details of open pediment, corner scrolls, & tied fleur-de-lys at base

These clear structural and ornamental links with another genre of Venetian frame, as well as echoes of the finish – the dark ground with parcel-gilding and occasional polychromy – are interesting. In the book The Sansovino frame, which accompanied the exhibition of the same name at the National Gallery in 2015, the authors remark that,

‘It seems possible that most of the early independent Sansovino frames were made for sacred images. / In this connection it is noteworthy that Sansovino frames were used on a miniature scale, in bronze, copper or silver, for the small relief sculptures kissed by the priest during the Mass at the words “pax Domini” and then passed to the congregation receiving the Holy Sacrament’ [43].

Venetian tabernacle frame, 1580-1620, sunk-panel work in limewood laminated on pine, inlaid with differently-coloured marbles, finished with paint, lacquer & mordant gilding, replacement plaque at centre of predella panel, 54.5 cm. wide (no height measurement given), © Victoria and Albert Museum

This crossover with other forms of contemporary framemaking in Venice can also be found in versions of the small aedicular frames; for example a small tabernacle in the V & A combines the entire structure of a ‘Corneille de Lyon’ aedicule with Sansovinesque scrolls and acroteria at the top, scrolling brackets at the sides, and an apron with further scrolls, echoing a tied fleur-de-lys, in the apron at the base.

The aedicular form of all these frames, perhaps with additional support from the connection with ‘Sansovino’ frames and their use for sacred paintings, provokes the inevitable question, what were these small frames – the so-called ‘Corneille de Lyon’ frames – designed for? – what was their contemporary purpose?

In The sacred home in Renaissance Italy, the point is made that from the 15th century,

‘…household devotional images often consisted of small diptychs or triptychs with side panels that could be closed when the image was moved, or simply hidden during daily life. …The wooden frame would often incorporate a stand, allowing the image to be placed on a table or prie-dieu, like a miniature altarpiece.’[44]

Later on, shutters became less necessary as these small sacred images became part of the permanent furniture of the private domestic quarters of the house; although cloth covers may have been used to protect them, and to heighten the moment of revelation of the image to the worshipper:

‘In 1548 in Venice, for example, we find “a small gilded image of the Madonna with its green cloth”, and “a picture of Our Lady with its handkerchief”.’ [45]

Pietro Facchetti (attrib., 1539-1613), The Petrozzani family at prayer, second half 16th century, o/c, 163 x 220 cm., Museo di Palazzo Ducale, Mantua

And, as also noted in the ‘Sansovino’ catalogue,

‘During the 15th and early 16th centuries, sacred images – frequently paintings, sometimes sculpture – were displayed in bedchambers and at street corners in ‘tabernacle’ or ‘aedicular’ frames…’[46]

Furthermore, the authors go on to say that,

‘…independent portable picture frames have all been removed from their original settings and it is easy to forget that they are closely related to the furniture that once kept them company…’ [47]

while,

‘…in 1593, the Venetian patriarch Lorenzo Priuli asserted that the use of domestic altars in Venetian homes was a time-honoured tradition… Inventories suggest that an image of the Virgin was typically to be found near the bed in the main living chamber, usually listed in conjunction with other devotional articles such as candlesticks, a crucifix, a holy water stoup, and a rosary, perhaps near an altarino or a banca da predella (prie-dieu).’[48]

It is highly probable, therefore, that in the later 16th and early 17th centuries, these small lacquered frames functioned as the settings for portable domestic altarpieces, which could have formed a part – however unlikely it seems now in our sadly secular world – of the suites of small lacquered objets d’art, comprising writing cabinets for men, and toilet chests, jewellery caskets and looking-glasses for women, along with musical instruments and bookbindings, various pieces from which would have furnished the 16th century Venetian bedchamber, studiolo, boudoir, etc.

Tuscan aedicular frame, early 17th century, ebonized wood inlaid with coloured stones & marbles, gilded bronze mounts in the form of St Michael & two female figures, 18 ¾ x 12 ¼ ins (47.6 x 31.1 cm.), now holding a modern piece of mirrored glass, Sotheby’s, New York, 30 January 2014, lot 345

When the Venetian frames are compared with similar frames from other regions of Italy, this becomes an even more probable function. The Florentine frame above, now in use as a looking-glass, has a figure of St Michael on the crest of the pediment, probably because this was the patron saint of the commissioning client, indicating that it would probably have held a painted scene connected with St Michael for use in a bedroom or private oratory.

Guglielmo della Porta (attrib.; c.1515/20-1577), Crucifixion, c.1565, wax relief on slate, 27 x 18 ½ ins (68.5 x 47 cm.); frame of ebony & pietre dure, beginning 17th century, Galleria Borghese, Rome

This is a comparable, slightly larger frame, also made in the early 17th century, almost certainly in Rome, and probably specifically for the wax relief by the Genoese-trained Fra Guglielmo which it encloses. He was an architect and sculptor, running a workshop which apparently included,

‘sculptors, goldsmiths, carvers in ivory, woodworkers, and other specialists.’[49]

This assemblage of talent would have given him the ability to have the frames for his own work produced on the spot; sadly the discrepancy in dates between his death and the approximate date of the frame precludes this being an original, but this relief – or the bronze or silver relief which would have been cast from it – would probably have been framed in a very similar style.

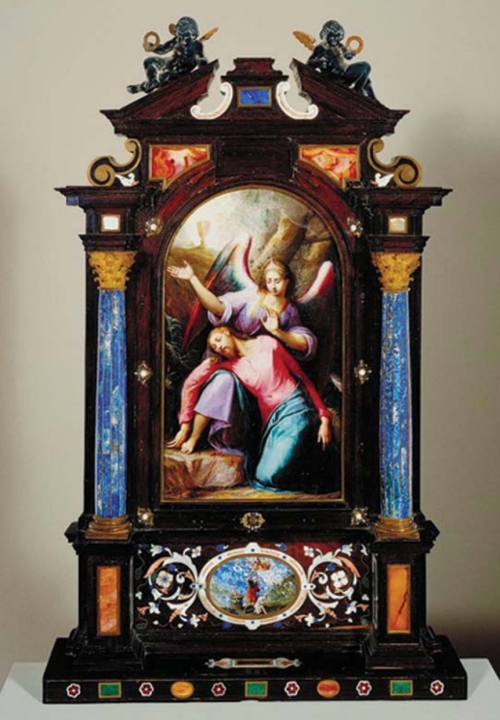

Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1626), Christ on the Mount of Olives, 1608, o/copper, 10 ½ x 6 3/8 ins (26.6 x 16.1 cm.); portable altarpiece, semi-precious stones, enamel, glass, metal; wooden & velvet-lined carrying case with doors closed; Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin

One small altarpiece frame which still retains its painting is this exquisite and beautifully-integrated work by Jacopo Ligozzi. In fact, it has not only kept its original painting, but also the carrying case created to transport it safely wherever its owner (possibly a Medici or a high-ranking member of a Jesuit order) went [50]. The subject of the altarpiece, the Agony in the Garden, is reflected in the cartouche on the predella panel, showing the sacrifice of Isaac. The frame exploits the amazingly rich and saturated colours of the stones used for columns and inlays in counterpoint to the pure Mannerist colours of the painting; this opulence is a stage further in enrichment even than the Tuscan frame with St Michael, shown above; again, it would have taken its place in a private chapel, study or bedroom, and might well have been echoed by other furnishings and fitments (pietre dure tables, caskets or cabinets) decorated with the same materials and techniques.

Galeazzo Mondella (called il Moderno; 1467-1528), pax with The Dead Christ and the Virgin, early 16th century, parcel-gilt silver, enamel; frame with cameo, mother-o’-pearl, ivory, bronze, 23 x 12.8 cm., Museo Diocesano, Mantua

Other sacred images which might have been set into small aedicules include metalwork paxes in silver, silver-gilt or bronze (as mentioned above in reference to small versions of ‘Sansovino’ frames); inventories suggest that these were used for domestic devotions, not only for liturgical practices during a public Mass [51], and they may have been framed at a later period than the date of the pax itself to take their place in the Renaissance home. These would fit as comfortably into a Venetian lacquered aedicule as into a central Italian pietre dure frame. However, until and unless a surviving example of a lacca da Venezia frame turns up complete with its native contents, we can only imagine (perhaps with the help of Photoshop) what these refined and beautiful objects originally looked like.

Venetian tabernacle frame, 1580-1620, V. & A., montaged with Sebastiano Filippi (called il Bastianino; c.1532-1602), The mystic marriage of St Catherine of Alexandria, 1560-1570, 46 x 32 cm., Museo d’Arte della Città, Ravenna

*******************************************

[1] Frame-oriented art historical research is always complicated by the lack of in-frame photography by museums as well as auction houses. If for some reason I have not been able to study a specific painting and frame in situ or through good photographical reproduction, I was limited by a rough stylistic analysis

[2] Anne Dubois de Groër, Corneille de la Haye, dit Corneille de Lyon, 1996, p. 16

[3] Ibid., p. 271. His request was declined on the grounds that there were no exemptions – although in 1559 he did receive exemption.

[4] ‘Corneille de Lyon’ is deliberately used in this essay, since it is the name the painter is best known by (others are Corneille de la Haye, Corneille de Laye and erroneously: Claude Corneille).

[5] Corneille’s travelling to Lyon makes more sense if he had worked in Flanders, since several Flemish artists also went there

[6] Where Bisacca (ibid.) uses the term ‘tabernacle frame’, the secular nature of the Corneille portraits calls for the less ecclesiastical ‘aedicule’ or ‘aedicular frame’. ‘Aedicule’ comes from the Latin for ‘building’, and suggests a frame like the silhouette of a Gothic cathedral (during the early Renaissance), or like the silhouette of a classical temple (later on). A tabernacle is properly, in any case, a wall-hung rather than a free-standing object, with a shaped apron at the base.

[7] See brief biography of Macchietti

[8] Of this group, four are definitely works by Corneille de Lyon, and the other five are either attributable to his workshop, or are now considered to be by another artists. The previous owners of these latter five almost certainly considered them genuine works by the master himself. The nine appear in Groër, op. cit., as figs 18B, 31B, 77, 126B, 129, 130, 178, 184, 208

[9] There are no known instances of Corneille making elaborate preparatory studies on paper.

[10] Number 457 (no frame)

[11] Groër, op.cit., pp. 136-137, cat. 31 A

[12] The dauphin François, son of François I. The second picture of the Dauphin mentioned in the inventory is six feet tall

[13] Numbers 67 and 159 both had gilt frames

[14] Numbers 383 (gilt frame) and 527 (no frame mentioned). The latter has not been identified as the one in the Gaignières collection. According to the catalogue raisonné, there is no evidence to support the idea that it was once in this collection

[15] Numbers 196 and 237 are both listed as from the Musée Condé collection. Another portrait of the duc d’ Alençon is listed as number 501 (gilt frame); however the size (2 feet 6 inches) noted there does not fit the Musée Condé portrait. Number 973 is also of the duke of Alençon, but it is a three-quarter length portrait

[16] Corneille de Lyon, Portrait of a man. René Huyghe, the curator of the paintings collection, classifies the works by Corneille de Lyon in the Walter Gay donation in the Louvre as ‘quasi unique’ in his study, La Donation Walter Gay au Musée du Louvre (Paris, 1937)

[17] Lamentations 1:12, from the Latin Vulgate

[18] There is an interesting parenthesis in the letter from Monsieur de La Valette to Roger de Gaignières cited by Dubois de Groër (op. cit., p. 282). La Valette describes finding a small portrait, definitely by Corneille, which he is able to buy – not for money, but in exchange for a book which La Valette had previously swapped a pistol for.

Anne Ritz-Guilbert, La collection Gaignières – Un inventaire du royaume au XVIIe siècle, Paris, 2016, pp. 66-67 : Gaignières started negotiating a price to sell his collection to the French king in 1710, signing a deal on 19 February 1711

[19] It is featured in the section referred to as ‘Portraits avec des bordures dorées. Les roys, etc.’.

[20] Groër, op. cit., p. 43 : The seal of Colbert de Torcy is on the back of all the paintings that Gaignières once owned; so in effect it can also be seen as the collection stamp of the Gaignières collection.

[21] Ibid., p. 43 : ‘Dans l’inventaire de la collection dressé par Clairambault, très peu de tableaux ont une attribution, mais parmi eux, sept sont donnés à Corneille:

– Deux petits tableaux du mary et de la femme, par Corneille, sans bordure

– François, dauphin de France, par Corneille, sans bordure

– Deux François de Scepeaux, mareschal de la Vieuveille, bordure dorée, Corneille

– Blaise de Montluc, marechal de France, Corneille

– Charles de la Rochefoucauld, comte de Randan, sans bordure, Corneille’

In a more recent online version of the Gaignières inventories, there are some differences to be noted, due to slight variations in the transcription.

[22] Inventory number 507: ‘Charles de La Rochefoucaud, comte de Randan, sans bordure, Corneille’.

[23] Inventory number 78. For the current frame…

[24] Number 144 (gilt frame).

[25] Number 157 (gilt frame).

[26] Number 156 (gilt frame).

[27] Number 187 (gilt frame), number 520 (no frame mentioned).

[28] Number 438 (gilt frame), number 140 (gilt frame), number 143 (gilt frame), number 188 (gilt frame)

[29] Number 467 (no frame mentioned).

[30] Several different terms were used: ‘bordure dorée’, ‘bordure de bois dorée’ and other variations, which may all be translated as ‘gilded’ or giltwood’.

[31] Metropolitan Museum of Art, inventory number: 1978.301.6.

[32] Metropolitan Museum of Art, inventory number: 49.7.45.

[33] Corneille de Lyon, Charles de Cossé; Metropolitan Museum of Art, inventory number 49.7.44.

[34] See also Anna Contadini, ‘Artistic contacts: present scholarship and future tasks’, in Anna Contadini & Charles Burnett (eds), Islam and the Italian Renaissance, Warburg Institute, 1999, pp. 1-60

[35] Maya Corry, Deborah Howard, Mary Laven (eds), Madonnas and miracles: The holy home in Renaissance Italy, exh. Cat., The Fitzwilliam Museum, 2017, p. 10

[36] Donald F. Lach, Asia in the making of Europe, 1970, vol. II, p.112

[37] Ibid. This lacquer was made from colophony, made from pine resin rather than insect secretions.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Miriam Rampazzo & Michele Di Foggia, ‘The sunk-panel book-binding of a Renaissance Venetian Commissione Dogale: the scientific examination of the decoration materials’, Heritage science, 12 March 2018

[41] Treccani Cultura: Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 85, 20016

[42] Compare the looking-glass frame designed by Vasari and carved by Alessandro Allori (in the Casa Vasari, Arezzo); this has a sliding cover on which Vasari painted the figure of Prudence.

[43] Nicholas Penny, Peter Schade, Harriet O’Neill, The Sansovino frame, National Gallery, London, 2015, pp. 16-17

[44] Abigail Brundin, Deborah Howard, Mary Laven, The sacred home in Renaissance Italy, OUP, 2018, p. 74

[45] Brundin, et al., op. cit., p. 72

[46] Penny, et al., op. cit., pp. 16-17

[47] Ibid., p. 19

[48] Brundin, et al., op. cit., pp. 72 & 70

[49] Ulrich Middeldorf, ‘Two wax reliefs by Guglielmo della Porta’, The Art Bulletin, vol.17, no 1, March 1935, p. 95

[50] Italian Renaissance & Baroque Art, Allen Memorial Art Museum

[51] Corry, et al., Madonnas and miracles, op, cit., p. 108