I’ve been looking at a lot of things since last post. I’m still trying to grapple with ancient metrology as described by some classical ancient authors. There has been robust discussion on GHMB featuring such luminaries in metrology and mathematics as as Jim Alison, Mercurial, molder, and magisterchessmutt, aimed at seeing how much truth there may be to ancient remarks about geography if it’s properly understood exactly which units of measure the ancient authors actually were referring to, or even by sorting out the ambiguity in the values for some of these uncertain and rather protean units of ancient measure by extrapolating from the geography described in ancient accounts.

For myself, I’d like to know if such research is able to turn the fantastical sounding descriptions of Egyptian pyramid measures into something sensible. If anyone would like to go ahead without me, the direction I’m currently heading in with that is that every time I get near the question of the size and content of the capstone of the pyramids of Cheops and Khafre (Khufu and Khafre), I keep running into what looks like the concept of a microcosm, with the capstone being a scale model of the whole pyramid across some hopefully astonishing proportion.

I find that quite remarkable given that the data comes from different sources over a span of thousands of years (the other thing I am currently considering is whether the account of Diodorus Siculus describing Cheop’s pyramid capstone might make sufficient sense if he were speaking in terms of Roman Cubits, rather than Egyptian ones).

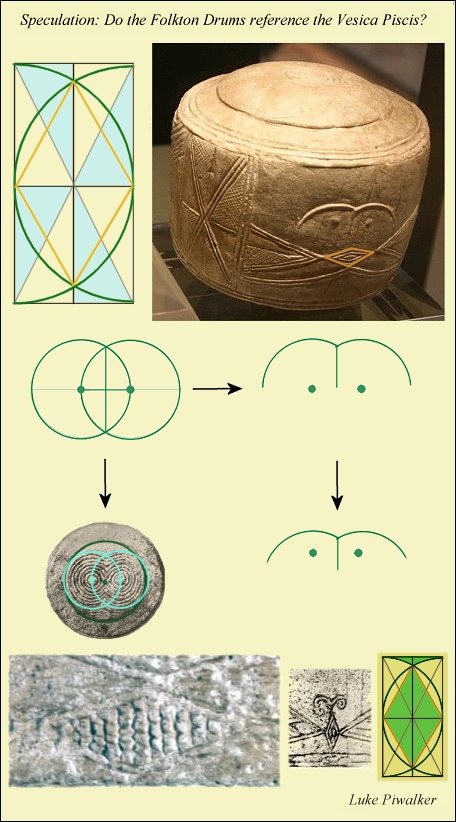

Meanwhile, I am quite honored that Cathryn Iliffe noticed some of my own observations about the symbols on the Folkton Drums and sent me a link to her papers on Academia.edu. Her paper Simple Solutions for Neolithic Construction Part 2 contains something something I find both very timely, and inspiring. It features a drawing of the Vesica Piscis shape inscribed with a circle and then a square and then another circle.

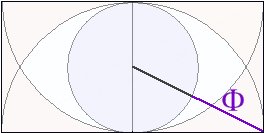

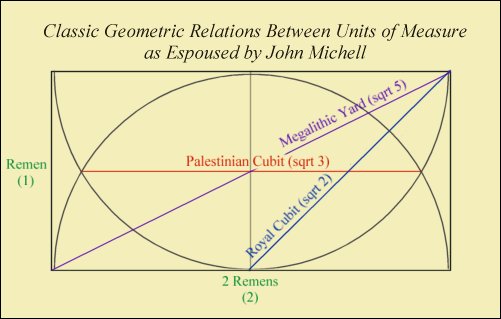

Some time ago I posted some metrological speculation concerning a model Geoff Bath was working on of the Great Pyramid’s King’s Chamber. I am still indebted to Geoff for pointing out that simply inscribing a rectangle measuring 2 by 1 generates the Golden Ratio Phi, adding this major geometrical constant to the classic square roots sqrt 2, sqrt 3, and sqrt 5 that are generated by this arrangement, and providing extra incentive for having used such outwardly simple-minded proportions as 2: 1 in the inner chambers of the mightiest Egyptian pyramid of them all.

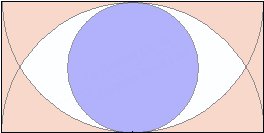

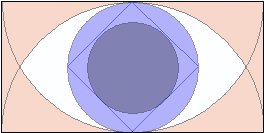

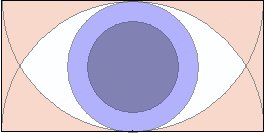

By the time we inscribe the Vesica Piscis with a circle, we have something that looks almost like an eye staring at us, except I haven’t been able to think of an acceptable way to provide the “eye” with a “pupil”. In suggesting inscription of the Vesica Piscis with what is an utterly classical exercise in geometry, I believe it’s quite likely that Cathyrn may have provided us with a definite way to obtain that missing detail.

I still feel a bit apologetic toward some old friends who are heathens – I know they are immensely understanding about “Old Ways” but I’m not sure if they ever quite understood why I sometimes feel a touch of a spiritual calling in the form of mathematics and geometry and puttering around with a pocket calculator.

I thought of saying “They don’t call it ‘sacred geometry’ for nothing”, or explaining some of the ways attributed to the Pythagoreans that make these subjects that are probably as boring to the average person as watching paint dry, into something at very least bordering on the truly magical, and how the Pythagoreans were said to have revered the apple because of its internal five-fold symmetry, which reminded them of the five-pointed star (pentagram) that can be used to represent the motions of the planet Venus, or how figures for the periods of Venus can be generated from the internal geometry of the pentagram.

The internal geometry of an apple revealed by slicing thought it horizontally.

For myself, my fascination with “sacred places” like stone circles soon runs into their geometry, and the recurrence of the geometry of the Vesica Piscis in many of them, just as it is also found inside Egypt’s greatest pyramid.

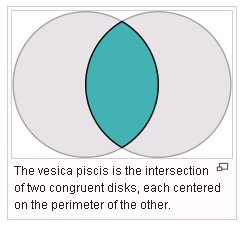

Wikipedia’s presentation of the basic origin of the Vesica Piscis, two equal circles overlapping by half.

I should be so lucky that any of them will ever end up reading this, but for their sake or for the sake of anyone to whom all this isn’t quite as familiar as the back of their own hand, since I have some layered diagrams that I made to better model what Cathryn’s paper suggests to call upon, I though I might take the opportunity to try to explain the Vesica Piscis in a little more of a “one step at a time” manner.

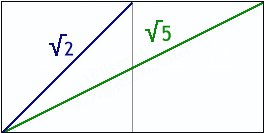

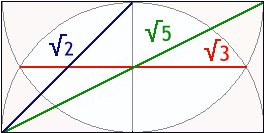

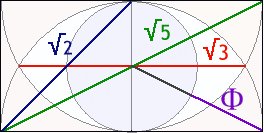

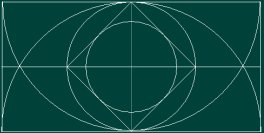

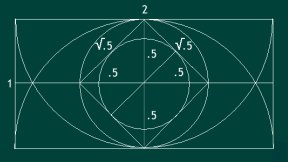

Step 1: We draw a rectangle measuring 2 by 1, then divide it in half. This provides both sqrt 2 and sqrt 5 as diagonals if the short side of the rectangle is 1.

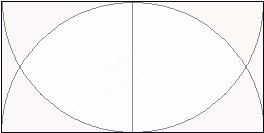

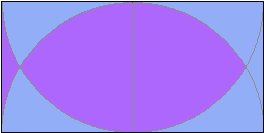

Step 2: From the center of each of the long sides, we can draw a half-circle the same diameter across as the length of the long sides of the rectangle.

Step 3: If we connect the two points where the two half-circles meet, the length between them is sqrt 3 if the length of a short side of the triangle is 1. Another sacred geometry constant is thus generated by continuing with the Vesica Piscis design.

Step 4: If we inscribe the Vesica Piscis design with a circle, the distance from the outside of that circle to corner of the rectangle is the Golden Number or Golden Ratio, Phi.

Step 5: Now we have sqrt 2, sqrt 3, and sqrt 5, and Phi in our collection of sacred numbers generated by a 2:1 rectangle. These aren’t just some funky numbers with specialist appeal to math geeks, all of these numbers have been part of sacred teachings over the ages and all of them help to govern the units of measurement that the ancient Egyptians and others actually used.

Intermission: It’s here I want to take a moment to try to sort out something before I forget. Awhile back when I posted my metrological interpretation of Geoff Bath’s model of the Great Pyramid’s King’s Chamber, not only was this new to me, but at the time I was struggling with trying to work out a very complex system of ancient measurements resembling that of metrologist John Neal. Thus the distance from the outside of the circle to the corner of the rectangle came out a “modified version of the Egyptian Royal Foot”, the “Medium Hashimi Cubit”

This latest exercise has been beneficial in that respect, because during the proceedings it was discovered that the true identity of this measurement inside the King’s chamber may actually be the Megalithic Foot, as in Harris-Stockdale Megalithic Foot.

The King’s Chamber diagram as original posted. Note that the somewhat questionable “10 Medium Hashimi Cubits = 10.62323175 ft” figure = 12.5 / 1.176667521 and thus may well be more correctly identified as a value in Megalithic Feet of approximately 1.177245771 ft each.

Step 6: Returning to the Vesica Piscis step-by-step, we now have a design that resembles an eye. It might look more like one if we add another smaller circle for the pupil – but how do we know what is the right size to make the next circle?

Step 7: This is what Cathryn Illife’s design looks like. The size of a smaller contained circle can be regulated by adding an enclosed square.

Step 8: We can work out the mathematics of this design easily. The diagonal of a square is the length of its side times sqrt 2, as we can see back at Step 1. Since the diagonal of this square is 1, the width of the rectangle, its sides measure 1 / sqrt 2 = sqrt .5, which is also the diameter of the inner circle.

These numbers too may have help to govern the values given ancient units of measurement. In the King’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid, note the for circumference of the larger circle, because its diameter is in Egyptian Royal Cubits, to use the most ideal value for the Royal Cubit gives a circumference of 54/10, a value that is in modern feet, while the circumference of the smaller circle may be another value in Egyptian Royal Feet / Hashimi Cubits.

Now the eye design is complete.

The basic Vesica Piscis design alternately interpreted as the shape of a fish. I question the conventional “wisdom” that “Vesica Piscis” meant “fish bladder”; rather it seems more sensible to interpret as meaning something more like a “blister” in the shape of a fish. (In modern times a “vesicant” continues to describe “an agent which causes blistering”).

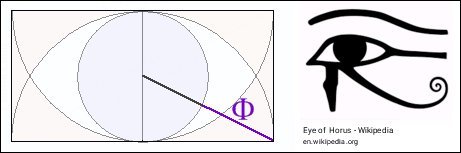

Here is something that to me seems quite remarkable: the ancient Egyptian sacred “Eye of Horus” features a diagonal line ending in a spiral, while the geometric design at left features a diagonal segment of the length Phi. One of the interesting things about the Golden Ratio Phi that often gets it mentioned in books on spirituality or ancient wisdom is that is associated with spirals found in nature, like those that occur in sea shells and flowers.

The “Eye of Horus” is frequently associated with a set of simple fractions known as “Eye of Horus Fractions“, but what the comparison above implies is that the Egyptians were of course far more skilled in mathematics than the very simple “Eye of Horus Fractions” give them credit for. However, this association with fractions does of course at least attempt to firmly associate the Eye of Horus with mathematics.

A consideration of some of the designs on the Folkton Drums from an earlier post of several weeks ago. It is absolutely remarkable how some of these features resembles fish or fish scales. The implication is not only that the Vesica Piscis and its association with fish is far older than anyone seems to have thought, but that the ancient Britons enjoyed an intellectual and scientific culture at least on a par with that of the ancient Greeks, in spite of any absence of written records to that effect.

The Vesica Piscis is referred to in the writings of Euclid, who is thought to have lived about 400-300 BC; The Folkton Drums are roughly dated to about 2600 and 2000 BC. How’s that for “Old Ways”?

–Luke Piwalker