April 10, 2008

Getting to know Carlos Pellegrini

Dr. Carlos Pellegrini is the Henry N. Harkins Professor and Chair of Surgery at the UW. He is also immediate past-president of the American Surgical Association, current president of the Society of Surgical Chairs, a regent of the American College of Surgeons, and a director of the American Board of Surgery.

This week, Pellegrini was made a knight in the French Legion of Honor, the highest award given by the president of the French Republic, in recognition of outstanding accomplishments and service.

He received his M.D. from the University of Rosario Medical School in Argentina, where he trained in general surgery. A world leader in minimally invasive gastrointestinal surgery, Pellegrini is a pioneer in the development of videoendoscopy and developed two major clinical research programs at the UW: the Center for Videoendoscopic Surgery and the Swallowing Center. He led the development of the UW Institute for Surgical and Interventional Simulation (ISIS) and was a major contributor to the reform of medical residency work hours in the United States.

Tell me about your early life and interest in medicine.

I lived in a very small town in Argentina — Amenabar in the province of Santa Fe — in the heart of the “pampas” (a vast plain). There were only two doctors in that town: one was my father and one was my mother. My parents practiced medicine in a very primitive setting. It was an Italian farming community with no electricity. I fell in love with the way they influenced and impacted every aspect of the community. They were personal counselors to the people living there, whether they had diabetes or depression, were planning a family or were unable to become pregnant. There was no hospital, so our home was the place where patients who needed “hospital” care would come and stay.

What brought you to the U.S. and eventually to the UW?

I came to this country from Argentina in 1975 during the military regime that had started in the 1960s and ended with the 1982 Falklands War. This rather dark period in the history of Argentina was characterized by a repressive dictatorship that used every means available to fight what is now known as “The Dirty War,” a war in which a lot of people disappeared. I went to the University of Chicago, where I completed my training in surgery, and then to the University of California, San Francisco, where I was for nearly 15 years. Then the opportunity came up at the University of Washington to become chair of the Department of Surgery.

What changes have you seen in surgical education since coming to the UW?

One of the most significant changes, particularly for surgery and the surgical specialties, was the regulation of work hours for residents. Prior to this, there was no limit to the number of hours residents worked — in surgery it was common to work between 110 to 120 hours per week. Then the American Council for Graduate Medical Education decided that residents could work only 80 hours per week. It was a movement to humanize the residents, to put value into the development of the whole person, and to attract into surgery the best and the brightest. We realized this would do away with the traditional way our residents cared for patients, providing continuity of care by being involved in the patient’s care 24 hours a day, seven days a week. So we put the emphasis on developing the best transfer of care system possible to allow the residents to safely and efficiently transfer care without feeling like they were abandoning patients.

And other major changes that have taken place?

As we became less tolerant of errors and the potential for threats to patient safety, we shifted away from the traditional apprenticeship model of teaching to a model that focused on the use of simulation to develop technical skills. This requires the creation of environments that are as close as possible to reality. It also requires the time necessary for residents to practice in those environments and for faculty, technicians and others to ensure the practice occurs and the skills are developed in the right fashion.

The introduction of simulation was a major advancement of these last few years, and one in which this department has been centrally involved. That’s how ISIS was born. Dr. Paul Ramsey charged me with developing a learning platform based on simulation and modeling to be used by students, residents and others at UW. A system that would be truly “learner-focused” and would advance the concept of “patient-centered” care since the system would prepare doctors to treat patients in a safer and more efficient way. This led to the development of ISIS — and I have led this movement across the U.S.

Describe your work as a pioneer in the development of videoendoscopy.

In the late 1980s, the discovery and development of a small camera that could be attached to the end of a telescope and project an image onto a monitor led to the development of minimally invasive surgery. The concept was used by general surgeons first on the gallbladder. I had been involved primarily in esophageal surgery, and I thought it presented a perfect field for the application of minimally invasive techniques because many of the operations done on the esophagus were relatively small. The biggest challenge was reaching the esophagus, and for that we had to make a very big incision, in the chest or abdomen, to put our hands in there to get to the site. With this new technique, we could simply cut a small hole in the chest or belly. We started seeing an immediate impact. Many more patients sought surgical treatment for esophageal diseases than before because they were no longer afraid of the pain and potential complications that could result from a big incision.

What is the Swallowing Center?

It’s where we study the function of the esophagus and the stomach and the relationship between the two. For example, reaction to acid that may be refluxing from the stomach to the esophagus, or a scar that doesn’t allow food to pass, or a disease in which the muscle becomes very tight and causes a blockage to the passage of food. We look at the musculature of the esophagus and the stomach, which allows us to plan the operation in a much more scientific way because we have precise measurements of the muscle’s function. This is particularly important when minimally invasive techniques are used because we have to know exactly where to cut — and how much — to accomplish what we need to do. On the research side, we accumulate data about the physiology of the esophagus and the function of the esophagus and the stomach to help us answer questions about a given disease. And we provide a community service for other surgeons seeking consultations for their patients at the Center.

What lessons have you learned during the 15 years you have been chair?

First, that the most important resource that the Department of Surgery has is its people. Indeed, the staff and faculty of our department are a wonderful group of dedicated men and women from very diverse backgrounds who dedicate their professional lives to the mission of the department. Second, that in order to recruit everyone to our cause, the leadership must be able to generate and maintain their trust. The best way to gain their trust is to create an environment of mutual respect and transparency, where integrity and professionalism are core values. I am convinced that if fairness guides the decision-making process, and if that is clearly apparent, everyone embraces happily the vision we have set, and enriches that vision with his/her own touch.

Who has most inspired you in your career or life?

My greatest inspiration came from my mother and father, and from my observation of the profound impact these two people had in their community. My mother was very involved with the school in our community, and after she died the school had a celebration of her life.

That was when I made a commitment to build them another school — and I did in 2001, on land that belonged to my parents. My mother’s main impact on that community, aside from her regular care of the people, was in education, touching every aspect of a person’s life.

As for what inspires me now, it is a combination of providing service to my patients and seeing my residents and younger faculty develop and succeed.

What languages do you speak?

Italian, French, Spanish, and English. I was born in Argentina from parents with European ancestry. My mother immigrated to Argentina from France, and my father was born in Argentina shortly after my grandfather emigrated from Italy.

What brings you laughter and enjoyment?

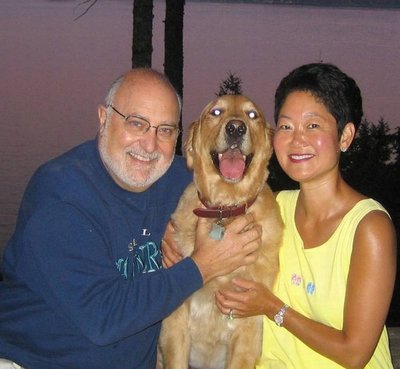

Most of the enjoyment in my life comes from my family. My wife is my greatest supporter and my greatest source of joy.

As for laughter, I love to laugh at myself and at the situations that life puts me in. I like to make fun of myself — and, occasionally, my friends. I enjoy my dog Dublin tremendously, and I laugh at the silly things he does. I like eating and telling stories about my adventures in life. What I really enjoy most is having a good meal at my house with my wife and a couple of friends, where you can cook together and chat, drink a little wine and have fun.