“Turn off your mind; relax and float downstream; it is not dying. Lay down all thought; surrender to the voice: it is shining. That you may see the meaning of within: it is being.”

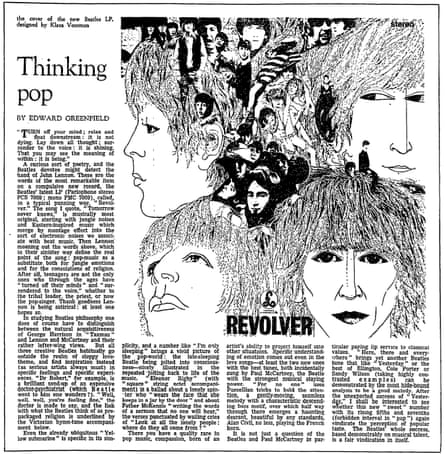

A curious sort of poetry, and the Beatles devotee might detect the hand of John Lennon. These are the words of the most remarkable item on a compulsive new record, the Beatles’ latest LP (Parlophone stereo PCS 7009; mono PMC 7009), called in typical punning way “Revolver.” The song quote, “Tomorrow never knows,” is musically most original, starting with jungle noises and Eastern-inspired music which merge by montage effect into the sort of electronic noises we associate with beat music. Then Lennon moaning out the words above, which in their sinister way define the real point of the song: pop-music as a substitute both for jungle emotions and for the consolations of religion. After all, teenagers are not the only ones who through the ages have “turned off their minds” and “surrendered to the voice,” whether to the tribal leader, the priest, or now the pop-singer. Thank goodness Lennon is being satirical: at least one hopes so.

In studying Beatles philosophy one does of course have to distinguish between the natural acquisitiveness of George Harrison in “Taxman” and Lennon and McCartney and their rather lefter-wing views. But all three creative Beatles habitually (as serious artists always must) in specific feelings and specific experiences. “Dr Robert,” for example, is a brilliant send-up of an expensive doctor-psychiatrist (which Beatle went to him one wonders?). “Well, well, well, you’re feeling fine,” the doctor is made to say, and the link with what the Beatles think of as prepackaged religion is underlined by the Victorian hymn-tune accompaniment below.

Even the already ubiquitous “Yellow submarine” is specific in its simplicity, and a number like “I’m only sleeping” brings a vivid picture of the pop-world: the late-sleeping Beatle being jolted into consciousness – nicely illustrated in the repeated jolting back to life of the music. “Eleanor Rigby” (with “square” string octet accompaniment) is a ballad about a lonely spinster who “wears the face that she keeps in a jar by the door” and about Father McKenzie “writing the words of sermon that no one will hear,” the verses punctuated by wailing cries of “Look at all the lonely people: where do they all come from?”

There you have a quality rare in pop music, compassion, born of an artist’s ability to project himself into other situations. Specific understanding of emotion comes out even in the love songs – at least the two new ones with the best tunes, both incidentally sung by Paul McCartney, the Beatle with the strongest musical staying power. “For no one” uses Purcellian tricks to hold the attention, gently-moving, seamless melody with characteristic descending bass motif, over which half way through there emerges a haunting descant, beautiful by any standards, Alan Civil, no less, playing the French horn.

It is not just a question of the Beatles and Paul McCartney in particular paying lip service to classical values. “Here, there and everywhere” brings yet another Beatles tune that like “Yesterday” or the best of Ellington, Cole Porter or Sandy Wilson (taking highly contrasted examples) can be demonstrated by the most hide-bound analysis to be a good melody. After the unexpected success of “Yesterday,” I shall be interested to see whether this new “sweet” number with its rising fifths and sevenths (forbidden interval in “pop”) again vindicate the perception of popular taste. The Beatles’ whole success, based demonstrably on musical talent, is fair vindication in itself.

The Beatles: A Band Reviewed - a selection of the Guardian and Observer’s reporting on the Beatles from the last 50 years - is now available as an ebook.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion