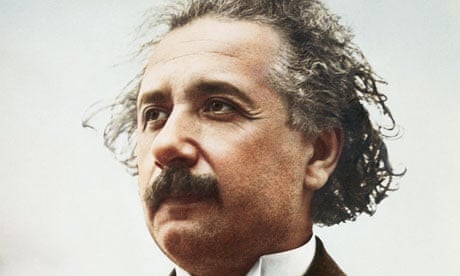

When Albert Einstein died in April 1955, he had rather immodestly left his brain for medical science. Seven hours after his death, Dr Thomas Harvey, the Princeton pathologist, was dissecting it. After pickling it in formalin, Harvey cut this unprepossessing object into 240 blocks the size of sugar cubes.

Soon there were sighs of disappointment from neurologists throughout the US, eagerly awaiting the results of these researches. Microscopy had revealed nothing extraordinary about this amazing man's intellectual powers. The bottle containing bits of brain was placed on a shelf where it gathered dust.

More than 20 years later, the bits were found in Wichita, Kansas in two bottles marked "Costa Cider". How they got there, how they were decanted into a jar marked "mayonnaise", and how investigations disappointed subsequent researchers throughout the 1980s is beyond my scope here. But the eagerness with which thousands of scientists wanted to know about Einstein's brain tells us about his unique contribution to knowledge.

Einstein was not an obviously gifted child. He didn't speak until nearly three, was ponderous physically and slow in answering questions, poor at languages and a failure at school. Only at 16 did he show some aptitude for mathematics and science. There was nothing to indicate that this loner was to become the leading scientist of the age, possibly the greatest genius since Isaac Newton, born more than two centuries earlier. Now he is considered one of the greatest physicists of all time.

Newton had invented calculus, and identified laws of motion and mechanics and a universal theory of gravitation. But in establishing the complex foundations of modern physics – special relativity, quantum mechanics and a new theory of gravity – Einstein saw the limits of Newton's thinking. Yet he wrote generously in 1927: "The 200th anniversary of the death of Newton falls at this time. One's thoughts cannot but turn to this shining spirit, who pointed out, as none before or after him did, the path of western thought and research… he deserves our deepest veneration."

Among many other ideas, Einstein's considered the properties of light. He recognised that stars shed mass by emitting light, calculating that the mass of a body is a measure of its energy content, "E = mc2". His breakthroughs changed physics, leading to nuclear energy and the bomb. His crowning idea was general relativity, which predicts surprising effects of gravity on light, and led, among other things, to our understanding of black holes. Einstein understood that light was emitted not merely in rays but as particles called photons. Thus, many years later, the optical laser was developed. Used in microscopes, eye and abdominal surgery, nuclear fusion, CDs and DVDs, supermarket bar-code readers, gene-sequencing machines, telecommunications and measurement of distances, it is just one example of his influence on modern technology and how one of his original concepts has so many applications now.

One thing intrigues me about this violin-playing genius. Was he autistic? He seemed poor at expressing emotions. He communicated poorly as a child, and his use of language was late. His family relationships were bad and he treated his first wife appallingly. Long before their final separation, he wrote: "You will stop talking to me if I request it." Things were little better with his second wife, Elsa. Yet Einstein's good sense of humour argues against autism; perhaps the fact that extensive scientific studies of his brain posthumously provide no insight into his psychology might provoke him to chuckle.