Of the many advantages Maria Clara’s house offers, accessibility is not among them. First, you have to take a moto-taxi – aka, risk seemingly certain death on the back of someone’s motorcycle – which will race through the winding and chaotic streets of Rocinha, Brazil’s biggest favela. Then you walk up a perilous cobble path that at times appears to be almost entirely vertical. About halfway up the path, you might spot a house on your right that, from the outside, looks like nothing much. At this point, you have to shout out to Maria Clara and, if she hears you, after several shouts, she’ll peer over the roof and throw over the key to the door. At this point, you – and maybe your luggage, maybe not – have arrived at your hotel.

Well, hotel is not quite the right word. “Not a bed and breakfast either – we are a republic here,” says the grinning Maria Clara, a smart and wiry grandmother who plies visitors with sweet coffee and biscuits, and she has many visitors these days. Since January, she has opened up her deceptively spacious house to guests, who live there with her and her family. She is completely booked up during the World Cup, mainly with American and Mexican fans who sleep on bunk beds in her back rooms and eat supper with her and her family on the roof terrace.

Rio de Janeiro is notably lacking in World Cup bunting and decorations, making a sad contrast to 2010 when it was covered in yellow and green, and this is a notable and a pointed expression of the city’s, shall we say, ambivalence about the World Cup. Maria Clara’s roof terrace, by contrast, is decked with World Cup decorations because, while she certainly has her qualms about the event, she has also found a way to make it work for her:

“If Fifa could, they’d take the stadiums with them when they leave, along with all the money. But when I saw big companies in Rio starting to make money from the World Cup I thought: ‘Why can’t I do that, too?’” she says. And she has certainly found a way to make it work for her: her rates have more than doubled for the World Cup to R$90 (about £23) a night. “Many of my friends,” she says, not surprisingly, “are now taking in guests in the favela …”

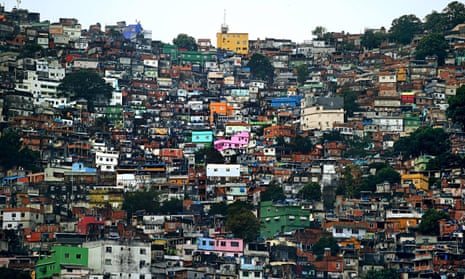

“Favela” is generally translated as “slum”, but that isn’t quite right. It’s more like a community. Each one has its own character and Rocinha’s is bright, bustling and almost overwhelmingly friendly. In the past decade Rocinha, while still comparatively rough, has changed to an almost recognisable extent: a 2008 project has installed a library, an emergency health clinic and a swimming pool for the residents.

The somewhat unfortunately named favela pacification programme also brought some improvements, but Rocinha residents complain, too, of the downsides: yes, they like that they now have street cleaners and some sort of rubbish disposal system, but they’re less keen on the constant presence of police who they say don’t understand their ways. Others speak more darkly of police abuses.

“I still eat breakfast, lunch and dinner to gunshots outside. Do I feel safer? I’m too scared to answer that question,” Maria Clara says. “It’s good the government have made improvements, but how about dealing with all the people who have sewage running through their backyard?”

Nonetheless, the cleanup and, in some cases, full-on gentrification, have made the favelas in the south zone of Rio an increasingly popular place to stay, and never more so than during the World Cup when hotels have jacked up their prices beyond belief. Matthew Wilmington, 25 and from London, is staying in the Babilonia favela in Rio after seeing a recommendation on Facebook: “I decided to come to the World Cup back in December and wanted to combine it with time in Rio between England games. My mate and I are so much happier we’re in a favela: our friends are all in some Ibis or something and it’s rubbish and expensive, whereas the woman who runs our house makes us dinner every night. We feel safer in the favela than we do on Copacabana beach.”

About 10 minutes from Maria Clara’s house, down a rubbish-strewn path and up a staircase so narrow your shoulders touch the sides, three Chile fans – one wearing a Beckham LA Galaxy shirt – are blearily recovering from the triumph over Spain the night before. Their landlord moved out of the house so as to be able to fit in more guests and they are certainly crammed in: three bunk beds are packed so tightly together in the bedroom you could roll between them without hitting the floor. But the Chileans love it:

“It’s not like we’re poor, but the hotel prices were out of control,” says Francisco Fredes from Santiago. “People had warned us beforehand not to wear a watch in the favela but I do and it’s been totally fine. We’re very happy here.

“It’s not entirely easy,” says Elliot Rosenberg, the founder of Favela Experience. “Some guests expect things to work the way they do in the developed world. It is definitely a problem for them if they lose their internet connection,” he adds with a palpable eye roll.

Rosenberg set up his company, which arranges home stays for tourists in Rocinha and nearby Vidigal, as a way to help the favela residents. Many, particularly in the increasingly chic Vidigal, are being priced out of their homes by developers, so Rosenberg saw this as a way to increase their income.

Tourists have been visiting the favelas for a while, particularly on the popular tours, where they stare down at the residents from jeeps as if they were looking at animals in a zoo. The favela home stays, Rosenberg says, are precisely the opposite of that: “That kind of tourism has no positive impact on the community and it is often run by outsiders who can’t give a real sense of the favelas. We want to improve the esteem of the favela dwellers and break down stereotypes about favelas to outsiders.”

Even though the favela prices have doubled during the World Cup, those Rosenberg looks after are completely booked out, with more than 150 guests staying in them in total. Because the people who opt to stay in favelas are a fairly self-selecting group, Rosenberg says there haven’t been any problems with them. “I’ll be honest, I was worried about the England fans beforehand, but they’ve been fine. The sort of people who want to stay in a favela are generally culturally sensitive.”

It would be hard to find someone who sums up the sheer variety and fluctuating fortunes of the favelas more than Maria Clara. As well as now being a hotel landlady, she is a funk singer – under the name Mulher Maracuja – and a herbalist, under the name of Mão Santa or “Sacred Hands”.

She was also, until relatively recently, homeless and lived on the streets of Rocinha for eight months with her five children after being accused by authorities of flouting planning laws. But thanks to friends and money earned through singing, she bought her house and is proud of the alterations she has made for her “gringo guests”. She recently rewired it and covered up all the exposed brick and woodwork with plaster.

“When I grew up in Rocinha, my house used to flood every time it rained,” she recalls. “Now, I have guests booked to stay in my house up until December. I love it. I want to do this for ever.”