Du mußt dein Leben ändern. You must change your life, says Rainer Maria Rilke’s Archaic Torso of Apollo (translation by Stephen Mitchell). Not modify your life. Not change your lifestyle. Not take more exercise. Your life. Change it. All good books change your life in some respect, if only by extending your knowledge and possibly changing your perceptions. Some lead you to a comprehensive change in direction. I know one man who lost his Catholic faith by reading Samuel Beckett. Another decided to go to university after reading Jude the Obscure. There are formative books of course, which is not the same. A good many books “formed” me, but the book that undid something in me and undoes it each time I look at it is the old Penguin, Rimbaud Selected Verse, with an introduction and prose translations by Oliver Bernard. It is, effectively, the archaic torso by other means.

I had already made the decision to be a poet, so that was not the change it wrought: it was more a revolutionary understanding of what being a poet meant, not in the sense that one might adopt a mannerism or two and strive to look as much like a boy genius as possible, but at the deepest, most visceral level. It was, and remains, the call at the bottom of the sea.

“You are not really serious when you are 17,” says Romance, Rimbaud’s poem about adolescent love. It is a relief to know that when you actually are 17, because then everything seems impossibly serious, especially love. The poem tells you that the girl is cute, that “the sap is champagne and goes straight to your head”, and that, at that age, is all it takes. And how old was Rimbaud when he wrote that? He can’t have been much older than 17 himself, since he started publishing poems at 16 and had finished with poetry by the time he was 21. Romance is, in some ways, a cavalier gesture, a shrug of the shoulders by someone who is heading into the fires of A Season in Hell and The Illuminations.

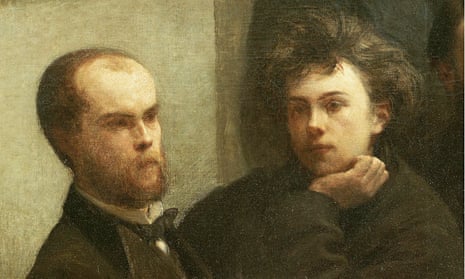

We must imagine a brilliantly gifted, unhappy boy, the pride of his school, who reels off alexandrines in an exam and wins prizes but who leaves behind his dull home and religiously oppressive mother in Charleville to go to Paris and become a Parnassian, a poet of pure polished forms, a role for which he was supremely gifted. He becomes a supporter of the commune. He has already written those extraordinary letters in which he declares that a poet must be a seer, and that poets must disorder their senses. There is the affair with Paul Verlaine. There is the shooting – Verlaine shot and wounded Rimbaud while drunk – and the trial. But far more importantly there are the magnificent defiant poems. Then the end – or as Martin Bell put it in a poem: “Rimbaud striding off to Africa” – to die in his 30s as a trader, never writing another poem.

Isn’t this simply the story of adolescence? And isn’t the reason people fall in love with both the poems and the figure because they are in love not with adolescence itself, which is painful and boring, but with the idea of adolescence? Isn’t it just the Prometheus myth, again and again? Life as conceptual art? But you can’t have the myth without the poems. They are not the poems of growing up – they are both process and product, the growing and the having grown in a unique temporary greenhouse.

I was nothing like that as a boy. I was middling, mendacious, shy and timid. Imagining being like Rimbaud was, as I well knew, simply imagining. I imagined a good deal then, at 16 and 17. Most of all I imagined failure and respite from failure. There was a point I wanted to be no more than a newsagent, reading behind the counter, dreaming and, yes, imagining, surviving on a desert island of failure where one could fail in peace.

Maybe Rimbaud was wish fulfilment then? I don’t think so. I knew exactly what he was talking about in being another, about having to be a seer, about disordering those desperately lost senses, about wanting to get away from Charleville (in my case from a north-west London suburb) and a mother (from, forgive me, my mother).

The Penguin Rimbaud came with prose translations but, with my schoolboy French and Oliver Bernard’s precision of tone, the poems rose before me like small explosive miracles. I loved those Penguins anyway, the Baudelaire, the Rilke, the Goethe, the anthologies of modern verse from various languages. They were a world in themselves. But in Rimbaud’s case (Baudelaire was all dream) it was more than that: it was, and remains, a conscience, not just an artistic conscience but, however paradoxical this seems, a moral conscience.

True, I wouldn’t have been able to put it quite like that. That is how I am putting it now. There ought to be something at the core of art that is restless, dissatisfied, demanding, with just that adolescent puritanical zeal. There is no I in that place: it is elsewhere. The senses are rightly disordered, and maybe there is something seer-like there too, something with a deadly irony about its own perceptions which are, nevertheless, perceptions. That irony burns in Rimbaud and he gave up the art. We don’t. The Rimbaud figure is what he was when writing. Admonitory. Stern. Ridiculous. Wild. Perfect. True.