Margaret and Mary Gainsborough are holding hands in their father’s most famous portrait of his children. Margaret, aged five, darts forward to catch a cabbage white as Mary, a year older, gently tries to restrain her. Their treasured faces are as radiant as the shaft of sunlight through the glade that turns their dresses silver and gold. But the butterfly is almost disappearing from the scene and time’s shadow is beginning to fall. The day is brief and childhood will soon be over.

The truth of Thomas Gainsborough’s great double portrait grows more apparent with every room of this small but powerfully affecting show. The artist (1727-88) painted his daughters together at least half a dozen times, and with each image they lose a little more innocent joy. Inseparable girls, arms draped around each other, teasing a cat, their thin young bodies twisting exuberantly inside stiff 18th-century dresses, they turn into uncertain young women immobilised by the latest fashions.

Gainsborough portrayed his daughters drawing, hoping they might take over the family business when he nearly died of some nameless illness around 1763. And he painted them as society beauties in copious satin, like the rich clients whose commissions paid for his house in Pall Mall. These two portraits are effectively advertisements, and it shows. You recognise Margaret and Mary from one painting to the next, and his unqualified love for these daughters who would be so unlucky in later life – one divorced within weeks of her wedding, the other suffering premature dementia. But in these full-scale portraits, Gainsborough’s brush is no longer so intimate, nor so quick with vitality.

Everyone knows that Gainsborough liberated portraiture from the old “licked” style of emollient smoothness, giving it an improvisational flourish that could put a spring in any idiot’s step and lend allure to the beefiest duchess. “Phizmongering” was his derisive term for a profession that subsidised his landscape art. But the 50 portraits in Gainsborough’s Family Album were made for love not money. No other 18th-century artist left so many images of his relatives – parents, uncles, cousins, children, nieces, nephews and assorted pets – and this is not simply because Gainsborough had an unusually large family.

Here is his beloved father, dead three years but sketched as if in a vision; and his niece Susan, aged eight, pale and touchingly nervous before for her uncle. Here is Gainsborough’s sister got up in a towering wig and glad rags, next to a portrait of her carpenter husband, bare-headed and humble (the contrast a gentle joke). And Mrs Gainsborough appears as a teenage bride, the ruddy-faced mother of two girls and especially strong in her 50s, almost resigned to married life but still ready to voice a criticism.

She was pregnant when they married, but the child died at two. This spectral daughter makes a posthumous appearance in the earliest image here (and the only portrait of husband and wife together), a fledgling family out in the landscape. Mr and Mrs Gainsborough – prefiguring Mr and Mrs Andrews two years later – are curious dolls in an opposingly fluid landscape. This is a hymn to nature by other means: dog drinking from brook, emblematic leaves against his coat, wild flowers in his wife’s hands – except that she has no hands. Even so young, at 20, Gainsborough is ignoring what he cannot be bothered to paint.

The artist worked at speed. He could finish a face in an hour and sometimes went very little further. This show is full of half-finished shoulders, limbs and bodies barely sketched in. You see this rapidity even in the mature portraits of actors and playwrights currently on show in the Holburne Museum in Bath, where the central fact of a sitter’s temperament – pensive, intellectual, broken, as in the wistful portrait of the actress Mary Robinson – is what matters.

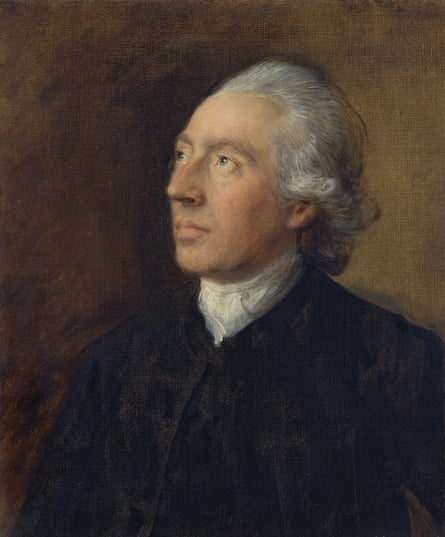

Turned upon himself, in eight self-portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, this quickfire brushwork ranges all the way from comedy to tragedy, sometimes fusing nuances of both. The mouth smiles, but the eyes don’t comply in a self-portrait from 1754, where a white-faced Gainsborough in an absurd tricorn hat looks like a sad clown out of Watteau.

A friend of his once praised Gainsborough’s letters as being exactly like his conversation: “gay, lively and fluttering round subjects which he just touched, and away to another”. The comparison with his art is generally held to be just as obvious. But what is so compelling about these family portraits, seen en masse, is the paradoxical combination of light touch and deep emotion.

So swift and impressionistic, so technically hasty, they nonetheless hold a presence strong and firm before you: the artist’s brother, a vicar, eyes to heaven against a glowering dark ground; his nephew and assistant, the painter Gainsborough Dupont, looking like a romantic Van Dyck. Above all the marvellous painting of Margaret trying to fix Mary’s hair – a scene of exceptional emotional intimacy.

The double portraits of his daughters exceed all others in their tender understanding. Even if you didn’t know it, you might deduce from this family album that Gainsborough had a complicated marriage – his restlessness chafing against her complacency – but the artist’s love for their children is pure, protective, infinitely observant. He appreciates the flawless glow of their young skins, the unruliness of their short fine hair, the slight defiance of the younger towards the older – so familiar to any parent.

This show condenses the evolution of Gainsborough’s art in five concise galleries, from the small paintings made in Suffolk to the larger, looser society portraits produced in Bath; from the rapid studies to the landscape portraits, where figures sit together in glades or walk through semi-tamed woods. It seems a very long way from the family as cellophane dolls in a pastoral flummery to the profound late portraits, but the circularity of the show allows one to witness Gainsborough finding his freedom. He believed it would come from painting “landskips”, but it was right there all along in the portraits he so much resented.

In his last self-portrait, Gainsborough looks shrewdly undeceived. To those who knew him well, the sly swivel of the eye conjured all his sharp intelligence in an instant, and that was the point of the picture. It wasn’t a public performance but an intimate communication, dashed off like a letter to a friend. Gainsborough depicts himself in paint so thin and fine he is there but almost not there, fading into a ghost.

And that way of painting carries a mortal significance, just as in the butterfly portrait made 30 years earlier. Margaret and Mary appear in their sunlit moment against a landscape that is barely there at all; and even they are not quite complete. Gainsborough’s masterpiece is exemplary both as a portrait of two children who are not yet fully themselves and as an image of ephemeral youth made permanent even as it slips away.

Gainsborough’s Family Album is at the National Portrait Gallery, London, until 3 February

Three stars of the show

Mary and Margaret Gainsborough, the Artist’s Daughters, c1760-1

Gainsborough’s oil sketch of his daughters is amazingly observant and empathetic. Mary is adjusting her little sister’s hair as no adult would be allowed, and Margaret tolerates it with the slightly cross tolerance of the younger sibling. Gainsborough’s oil is as fluid as pastel and the image, so fragmentary and quick, seems as modern as a Degas. The picture was cut in two and wrongly reassembled by a Victorian collector. The girls would not have been eye to eye: Mary would have been taller.

Gainsborough Dupont, the Artist’s Nephew, 1773

The revelation of this portrait, when a century of filth was removed for this show, was not just the brilliant sky-blue of the boy’s satin jacket, but the fact that Gainsborough used tiny flecks of the same colour in the hair and eyebrows, and to bring forward the nose and forehead. He makes his nephew sparkle with life. Dupont was also Gainsborough’s assistant, and helped finish some of his works. They are buried together in Kew.

Self-Portrait, c1787

Gainsborough painted this unfinished three-quarter portrait for his friend the composer Carl Friedrich Abel, who died before he saw it. When the painter discovered that he himself was dying of cancer, at 61, he left written instructions that this most subtle and diaphanous self-portrait was to be the only sanctioned likeness after his death. This is how he wished to be seen and remembered, in an image of profound intelligence that seems present in the canvas like smoke in air.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion