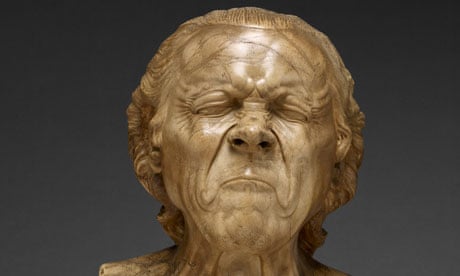

There is an infinite sadness to the art of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. Perhaps it is the lead and tin alloy from which he created his grey-glinting heads that weighs on the soul. Perhaps it is the resemblance to death masks that haunts his microscopically detailed reproductions of human physiognomy. But more likely it is the prison of his mental illness whose door slams on you as you are drawn into his extravagant monomaniac vision.

Messerschmidt was a brilliant Bavarian craftsman, born in 1736, who was headed for a career at the Habsburg court in Vienna until he exhibited psychological problems that denied him advancement and sent him deep inside himself to explore his own, personal invention, the "character head", a study of extreme emotional states that he typically either carved in alabaster or, in his most compelling works, cast in lead alloy. The Louvre has brought together a large proportion of his surviving works in an exhibition that brings you uncomfortably close to this lost soul of the European Enlightenment.

The unease of Messerschmidt's sculpture begins in aesthetics. He worked at a time when the loftiest model for a sculptor was thought to be the classical art of ancient Greece and Rome, and when the cult of antiquity was becoming more exact and passionate than ever before. Messerschmidt believes in this lofty classical idea of art: his heads have a dignified separation from their bodies (they sometimes look like they have been guillotined) and arise from slender tapered columns instead of necks. They are squared and measured and proportionate. Yet even in commissioned portraits of aristocratic faces he concentrates on fleshy wrinkles and stretched sinews in such a way that an abstract ideal mutates into ugly reality.

It is as if photographs have been inserted under the cool skins of sculptures. This realism is pursued with the greatest intensity and abandon in the contorted heads that are his most famous works. They are faces he pulled in front of a mirror. Laughter, despair, rage - he tries out emotions on his face and records the result with hyperreal classicism. It is utterly strange. No other artist of the age worked in a similar way, and you sense a long sickness of compulsive, isolated behaviour in what are nevertheless great works of art.

Later beholders – his works began to be talked about soon after his death in 1783 – gave descriptive titles to his contorted heads, attributing specific emotions to each one. Yet in reality it is often difficult to say what this square-headed, shaven-haired man is feeling. It is the same man, again and again, and as he lowers his eyes and squashes his chin against his chest, or screams silently with his mouth open like a black cave, what you sense is not so much the depiction of physiognomy as of the unfathomable self, alone and confounded, puzzled, grimly amused and fantastically assured of his own fascinating monstrosity: proud to be a severed head in a jar. Messerschmidt's metal muscles shine hard and polished against the light: he repels curiosity even as he commands it. He exhibits himself as a freak, and laughs at medical or philosophical attempts to understand him. In this compelling exhibition you see the age of reason melt in his alchemical furnace and give birth to a phoenix of madness.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion