The Mysteries of the Shroud of Turin

Editor’s note: This article appeared in full in the Feburary 2022 issue of Materials Evaluation. It was edited for length and some figures were renumbered.

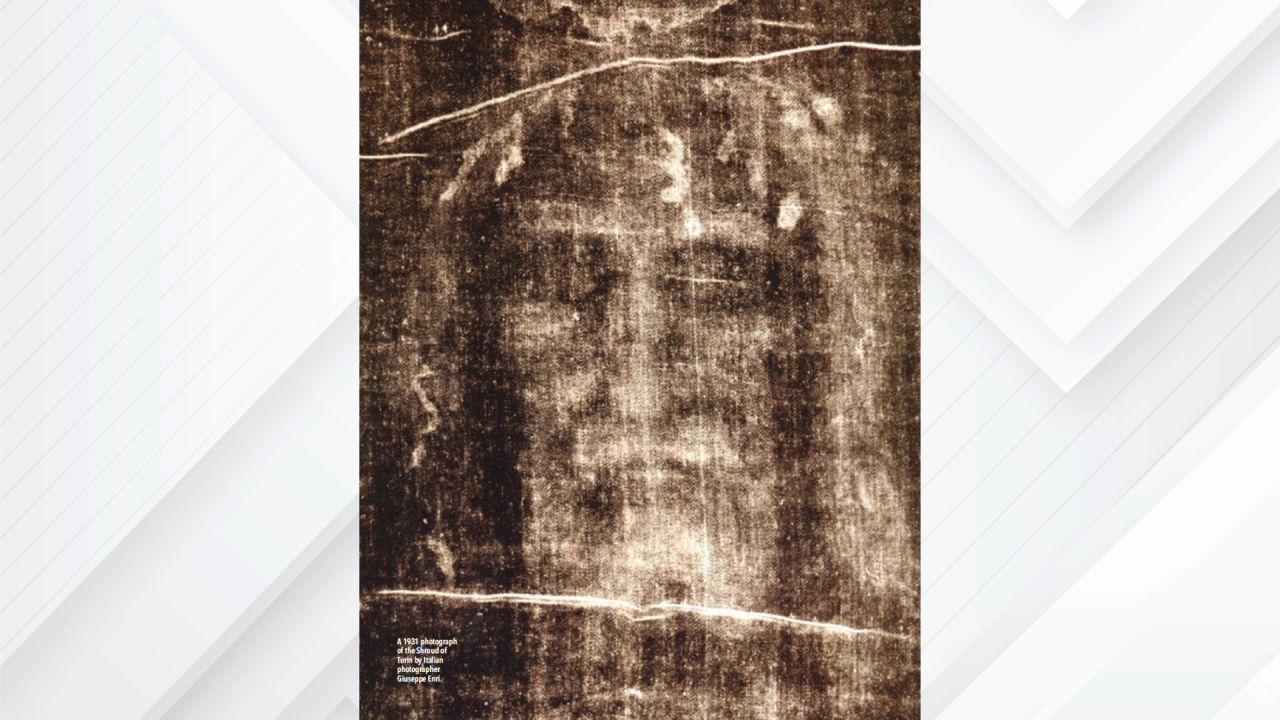

In 1931, a professional photographer named Giuseppe Enri pointed his camera at a piece of cloth called the Shroud of Turin and took the picture shown. How was this image formed? When was it made? Who made it? Is this an image of a real person? Could this be an image of the man known as Jesus Christ? Could this be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus? These are just a few of the questions that arise.

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most mysterious and potentially significant items in human possession. It has been featured on the cover of US News and World Report (1 March 2002) and Time magazine (20 April 1998). The June 1980 edition of National Geographic included a 24-page article with a four-page foldout of the Shroud. In the 1980s, the Shroud was briefly headline news around the world, but for reasons that will be discussed later, the Shroud has received little media attention for the last three decades. That is now starting to change due to four recent papers on statistical analysis published in peer-reviewed journals.

This article provides an overview of the Shroud, including its images, history, materials, and previous testing. It also includes the author’s hypothesis to explain the main mysteries of the Shroud. The purpose of this article is to encourage the development of a program for future testing of the Shroud.

What Is the Shroud of Turin?

A shroud is a piece of cloth in which a person is buried. Turin, also called Torino, is a city in northwestern Italy. Thus, the Shroud of Turin refers to a particular burial cloth that has been in Turin, Italy, since 1578. The Shroud is a linen cloth about 14 ft 4 in. long by 3 ft 8 in. wide (437 × 111 cm). It is about as thick as a T-shirt (about 0.35 mm) and is very pliable. Many people regard this cloth to be a holy relic because ancient tradition has long claimed it to be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus Christ. This claim is supported by the full-size front and dorsal (back) images of a man who was crucified exactly as Jesus was crucified according to the Gospels in the New Testament, yet extensive testing in 1978 indicated these images are not due to pigment, scorch, liquid, or photography.

What Do the Images Show?

In Figure 1, the top image shows the Shroud as it would normally be seen. It shows two long scorch marks caused by a fire in 1532 when it was in Chambery, France. Also shown are water stains resulting from water thrown onto the box containing the Shroud after the fire and 16 patches used to repair one burned corner of the Shroud, as it was folded in the box. The images of the crucified man can be seen between the scorch marks. The front image is on the left with head, arms, torso, and legs visible. The back (or dorsal) image is on the right, with the head toward the left and the feet on the right.

The bottom image in Figure 1 is the photographic negative of the Shroud, but it shows the body as a positive image. This means the images on the Shroud are negative images, with light and dark areas reversed. It is important to note there are no images of the sides of the body or the top of the head, and the front and dorsal images are head-to-head.

Vertical views of the images are shown in Figure 2. The front image shows puncture wounds in the scalp as would occur from a cap (crown) of thorns. It shows a swollen cheek, bent nose, and a 2 in. elliptical wound in the side the size of a Roman thrusting spear, with blood running down from it separated into red and clear components. The clear components contain blood plasma and clear watery fluid from the pleural cavity. This indicates the side wound is a postmortem (after death) wound.

The front image shows a nail wound through the wrist, contrary to paintings in the Middle Ages depicting crucifixion, which had the nails going through the palm. We now know a nail through the palm would not support sufficient weight because it would have no bones above it. The image does not show the thumbs, also contrary to paintings of the Middle Ages. When the nail was forced through the wrist at that location, it would have crushed the nerve that passes through that location. All the nerves from the fingers and the thumb connect into this nerve, so that crushing it would have forced the thumb to collapse into the palm. Thus, in both respects (location of the nail wound and no thumbs visible), the image indicates it was not made in the Middle Ages, contrary to the 1260–1390 AD carbon dating of the Shroud.

The front image also shows blood that ran down the arms from the wrist wounds, with two angles of the blood flow consistent with a man pushing up and down on the cross to breathe. About 120 scourge marks are visible as well as abrasions on the nose and one knee, suggesting the man had one or more falls. There is also a 3.2 in. wide side strip sewn onto the main Shroud using a unique professional stitch most similar to a stitch on a cloth from Masada, which was destroyed in 73–74 AD. This indicates the Shroud is probably from the first century.

The dorsal image in Figure 2 shows puncture wounds in the scalp and abrasions on the shoulders consistent with carrying a rough heavy object. Scourge marks are visible down the body consistent with two Roman flagra (scourge whip) containing dumbbell shaped weights on the ends of three straps, along with a flow of blood and clear blood serum and clear watery fluid from the pleural cavity that drained from the side wound and ran across the small of the man’s back. Also, two nails were evidently placed through one foot with only one of the nails through the other foot. This would permit one foot to be rotated to allow the man to push up and down to breathe while crucified. The shape of the feet, being twisted together, indicates the presence of rigor mortis. This indicates the man was dead on the cross long enough for rigor mortis to set in.

There are several unusual or unique features to the images on the Shroud. The images are negative on the cloth with light and dark areas reversed. They have no outline or brush strokes, and they contain 3D information (Jackson et al. 1984), which allows a 3D statue to be reconstructed from the 2D Shroud. No painting or photograph contains 3D information. Also, the Shroud contains no products of body decay. The front and dorsal images are head-to-head because the cloth was wrapped up the back of the body, over the head, and then down the front of the body.

A closer view of the face is shown on the opening photo in a positive image. This image contains an exact front view with long nose, mustache, beard, and hair parted in the middle coming down on both sides of the head, with the hair a little longer on one side than the other. This image appeared in paintings starting about 550 AD and was on coins starting about 692 AD. Thus, this image long predates the carbon dating of the Shroud (1260–1390 AD) and is the source of our concept of Jesus’s appearance.

History of the Shroud

The Shroud was brought into Turin, Italy, in 1578 and has been kept in the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Turin since 1694. Figure 3 shows a photo of the cathedral taken in 1978 when the Shroud was on exhibition in the cathedral. The Shroud goes on exhibition only a few times a century and when it does, millions of people slowly file past it to see the front and back images of the crucified man.

Materials of the Shroud

The Shroud is woven from linen thread made from the stems of the flax plant. In making linen thread, flax fibers are separated from the rest of the stem by allowing the stems to rot in water. The diameter of these fibers is about 15 to 20 µm, which is about a fifth of the diameter of a human hair. A typical linen thread contains about 100 of these fibers.

Previous Research on the Shroud

It is often said that the Shroud is the most researched artifact in human possession. Research on the Shroud can be divided into four periods. These four periods and their conclusions are summarized below.

1898 to 1977: The images were formed by a crucified man who was wrapped in the Shroud. This is indicated primarily by the nature of the blood on the Shroud.

1978 to 1987: Extensive experiments indicate the image is not due to paint, scorch, liquid, or photography. The methodology for image formation could not be determined.

1988 to 2016: The Shroud was carbon dated in 1988 to a range of 1260–1390 AD (two sigma). This allegedly proved the Shroud could not be authentic.

2017 to 2021: The 1988 measurement data was finally released for review in 2017. Statistical analysis of the data proved the samples were not homogeneous (that is, representative of the rest of the Shroud), indicating the certainty of the 1260–1390 AD date should be rejected because it may or may not be true.

Scientific testing of the Shroud began in 1898 when an Italian amateur photographer named Secondo Pia took the first photograph of the cloth. He would have expected his photographic plate to show a poor-resolution negative image of the face, but instead it contained a good-resolution positive image. This meant the image on the Shroud was a good-resolution negative image, with light and dark areas reversed. Therefore, the image could not be a painting because an artist prior to 1898, or 1578 or 1355, could not have painted a good-resolution image of what he had never seen (a negative image of a face). Research continued over the next eight decades by very qualified people in the United States and other countries.

Researchers in general concluded that the dead body of a crucified man had been wrapped in the Shroud and in some unknown way had encoded front and dorsal images of itself onto the burial cloth in which he was wrapped. This belief was largely based on the pristine, unbroken appearance of the edges of the blood clots, with their indented center and raised edges, and the clear blood serum extending beyond the blood clots due to capillarity.

The only opportunity for a comprehensive scientific examination of the Shroud occurred in 1978. The discovery in 1975 by John Jackson, professor of physics at the Air Force Academy, that the images contained 3D information led to the formation of the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP). In 1978, the Vatican allowed STURP, led by Jackson, to send 26 American scientists to Turin to perform nondestructive experiments on the Shroud for a total of 120 h. STURP’s experiments on the Shroud included:

light (up to 1000×) and electron microscopy

photography, various wavelengths, front and back

UV spectrophotometry of fluorescence

X-ray fluorescence and absorption radiography

thermal photography

mass spectrography

laser-microprobe Raman spectroscopy

attempts to alter color on fibers using acids, bases, oxidants, reductants, and organic chemicals

Testing was also done for the presence of protein in the images, and multiple tests were done to determine whether what appeared to be blood was blood. The conclusion of these tests indicated the presence of blood on the Shroud. But the main objective of STURP was to determine how the images were formed. They concluded the images could not be the product of paint, dye, or stain because there was no pigment on the fibers, no evidence of a binder to hold pigment, no brush strokes, no clumping of fibers or threads, no stiffening of the cloth, and no cracking of the images along fold lines.

STURP also found no capillarity (soaking up of liquid) in the fibers or threads, so the images could not be due to a liquid such as an acid or an organic or inorganic chemical in a liquid form.

A scorch caused by a hot object will fluoresce (emit light in the visible range) when exposed to ultraviolet light. When the Shroud was exposed to an ultraviolet light, the scorches caused by the fire in 1532 did fluoresce, but the images did not. This indicated the images were not formed by contact of a hot object with the cloth. The images on the Shroud could also not be the result of a photographic process because the images contain 3D information. Photographs and paintings do not contain 3D information.

STURP also concluded that only the top one or two layers of fibers were discolored out of about 100 fibers in a thread. This discoloration did not extend across the entire 15 to 20 µm diameter of the fibers but only discolored the fibers to a thickness of less than 0.2 µm, which is about 2% of the radius. In general, this thin discolored layer extends around the entire circumference of a fiber over much of the length of the discoloration.

STURP concluded this discoloration is not due to any substance or material (such as atoms) added to the fibers but rather is the result of a rearrangement of the atoms already in the fibers. The discoloration process can be described as a dehydration-oxidation process that formed the images of the crucified man. Specifically, the discoloration is due to some of the single electron bonds of the carbon atoms in the cellulose being changed to double electron bonds. This causes the molecule to vibrate differently so it reflects light differently, so it appears discolored.

What could cause the fiber to be discolored only on the outer 2% of the fiber’s radius? Various concepts have been proposed to explain this and other individual features of the Shroud, but the hypothesis of an extremely brief, intense burst of radiation is attractive because it is the only concept that is consistent with the evidence and can explain the three main mysteries of the Shroud—namely, image formation, carbon dating, and features of the blood (Rucker 2020a).

Mystery #1: Formation of the Images

The first mystery to be considered is formation of the images on the Shroud (Fanti et al. 2005). Three things are needed to form the images: a mechanism to discolor the fibers, energy to drive the discoloration mechanism, and information to control the discoloration mechanism. This information is needed to control which fibers are discolored and the length of the discoloration on each fiber, because it is the discoloration on the fibers that forms the images of the crucified man.

Why can we see the images?

The key to answering this question is information. For example, why can we recognize a person in a photograph? It is because the information that defines the person’s appearance (colors, shades, positions) has been encoded into the pattern of the pixels in the photo. The same is true for the Shroud. We can see the images of a crucified man on the Shroud because the information that defines the form of a crucified man has been encoded into the pattern of the discolored fibers on the cloth. (Rucker 2016). The information that defines the form of a crucified man was only inherent to the body that was wrapped in the cloth. It was not inherent to the limestone of the tomb. Thus, this information had to be carried, transported, or communicated from the body and be deposited on the cloth.

However, this information is not the information that defines how we would see the body in reflected light. Instead, it is the information that specifies the vertical distance between the body and the cloth at each point. This is the 3D information that is encoded into the images (Jackson 1989; Jackson and Jumper 1976). Because this information is the vertical distance between the body and the cloth at each point, this information was most likely deposited on the cloth by something that traveled vertically from the body to the cloth and was altered as it traveled vertically across the air gap. Radiation is the only option that can satisfy these requirements. It can travel vertically from the body to the cloth because both particles and photons of light travel straight in the direction in which they are emitted. They can communicate the vertical gap distance by their intensity (number of particles or photons), with the intensity being diminished by absorption and scattering in the air, and possibly by decay for particles.

Many, if not most, Shroud researchers believe the images were formed by radiation. Only vertically collimated radiation emitted from the body can communicate to the Shroud the information that is encoded in the images and deliver this information in a focused manner (Rucker 2020b). This would be necessary to produce the good resolution front and dorsal images with the correct width of the face while not producing images of the sides of the body or the top of the head.

Vertically collimated radiation allows each point on the cloth to have received information from only one point on the body: the point vertically above or below it. This one-to-one correspondence is required to prevent the information from becoming confused, which would cause a significant loss of resolution in the images. If the radiation had been emitted uniformly in all directions, then innumerable lenses would have been required between the body and the cloth to focus the radiation on each fiber to form the good-resolution images. Since such lenses would not have been between the body and the cloth, the radiation must have been vertically collimated. The radiation being vertically collimated is also the best option to produce the realistic width of the face that is on the Shroud.

Other characteristics of the radiation can also be determined. Laser experiments indicate that to produce the extreme superficiality of the images (with only the top one or two layers of fibers in a thread discolored and only the very thin outer layer of the fibers discolored), the radiation must have been emitted in an extremely brief and intense burst of radiation (de Figueiredo 2015).

What could have caused the fiber discoloration?

It is the discoloration on the fibers that forms the images. Thus, how the fibers were discolored to a thickness of less than 0.2 µm must also be explained.

[I]t is hypothesized the images were formed by an extremely brief, intense burst of vertically collimated low-energy radiation (primarily charged particles) that transported energy and information from the body to the cloth. This energy and information were required to form the images. Radiation from the body can explain why the images are on the inside of the wrapped configuration, why the images are negative images, why there is 3D information in the images, why bones (teeth, hands, etc.) in the body can apparently be seen in the images, why threads that are discolored produced a shadow in the discoloration on the fibers below them, and so on.

It is hypothesized this radiation caused an electrical discharge from the top fibers facing the body (Rucker 2019), which produced heat and/or ozone that altered the molecular structure in the thin 0.2 µm circumferential region of the fiber. This could have led to the images slowly developing as the fibers were gradually discolored in the thin region, probably over a period of months to years as the atoms settled into their lowest energy states. This gradual process is evidenced by experiments involving proton irradiation of linen (Lind 1989).

Mystery #2: Carbon Dating

The second mystery is the carbon dating of the Shroud.

In 1988, samples were cut from a corner of the Shroud and sent to three laboratories in Oxford, UK; Zurich, Switzerland; and Tucson, Arizona, for carbon dating (Figures 4 and 5). Results were published in 1989 in the journal Nature (Damon et al. 1989).

The mean* of the three laboratory mean values was 1260 AD ± 31 years (one sigma). This is called the uncorrected value. When corrected for the changing C-14 concentration in the atmosphere, a range of 1260 to 1390 AD (two sigma) was obtained. However, there are several reasons why most Shroud researchers believe the certainty of the 1260–1390 AD date should be rejected because it may or may not be true (Rucker 2020c). These include:

The technology to make the images did not exist in 1260–1390. It does not exist even today. Every attempt to make the images today has failed macro and/or microscopically.

There are 13 other date indicators that contradict the 1260–1390 date (Rucker 2020d).

The measured carbon dates depend on the distance from the bottom of the Shroud (Figure 6). This means the samples were not representative (not homogeneous) of the rest of the Shroud. The non-homogeneity of the samples has been confirmed by four recent papers in peer-reviewed journals (Casabianca et al. 2019; di Lazzaro et al. 2020; Walsh and Schwalbe 2020, 2021), and is consistent with previous statistical analysis of the measurement data (Rucker 2018).

The carbon dates from Oxford and Arizona are different by 104 ± 35 years, which is a three sigma difference (104/35 = 2.97). The usual acceptance criterion for no statistically significant difference is two sigma, so this indicates the dates have a high probability of being different. This should not be the case since both samples came from the same piece of cloth. This indicates something strange is going on. Technically, this indicates the samples are evidently not homogeneous due to the presence of a systematic error, which means the certainty of the carbon dates should be rejected.

A chi-squared statistical analysis of the measurement data (values and uncertainties) indicates the distribution of the measured subsample dates has only a 1.4% chance of being explained by the stated uncertainties (significance level p = 0.014 in Table 6 of Rucker [2018] and Table 4 of Walsh and Schwalbe [2020]). This indicates a systematic error was likely present. If a systematic error was present, then the certainty of the uncorrected mean value of 1260 ± 31 should be rejected, so the corrected range of 1260–1390 should also be rejected.

When the three laboratories measured the C-14/C-12 ratios of the Shroud subsamples, they also measured the C-14/C-12 ratios of samples from three cloths of known historical dates (Damon et al. 1989). The carbon dates obtained for these three standards were in reasonable agreement with their historical dates, which indicates the C-14/C-12 ratios were being measured correctly. Thus, it should be assumed the C-14/C-12 ratios of the Shroud subsamples were measured correctly. But if the C-14/C-12 ratios were measured correctly, then the systematic error cannot be in the C-14/C-12 ratio measurements, so it must have been in the samples. This means that something must have altered the C-14/C-12 ratios in the samples to produce the systematic error. Some believe this occurred when newer cloth was invisibly interwoven into the older cloth of the Shroud (Marino and Benford 2000), but this hypothesis cannot explain all the evidence.

When the carbon dates and one sigma uncertainties obtained by the three laboratories are plotted as a function of distance from the bottom of the cloth (Oxford, Zurich, and Tucson, shown left to right in Figure 6), a sloped, red-dashed line through the three points is a better fit to the data than assuming all three samples had the same date of 1260 AD, which is the black-dashed line. The slope in the red line is about 36 years per centimeter, which is 91 years per inch. At this rate, if the sample point is moved by 10 in., then the carbon date would change by 910 years; that is, from the uncorrected carbon date of 1260 AD to a future date of 2170 AD. Thus, this slope in the carbon date could be very significant.

The hypothesis that is consistent with everything we know to be true about carbon dating as it relates to the Shroud is the neutron absorption hypothesis (Rucker 2020c). If the radiation emitted from the body that caused the images also included neutrons, then a small fraction of these neutrons would be absorbed in the trace amount of nitrogen in the cloth to produce new C-14 in the fibers (Lind et al. 2010) by the

This production of new C-14 would cause the carbon dating process to produce a more recent carbon date than the true date. For example, the carbon date would be shifted from 33 AD to the midpoint of the range 1260–1390 AD by an increase in the C-14 atom density in the samples of only 16.9%. Based on a series of nuclear analysis computer calculations (discussed below), this would occur if 2 × 1018 neutrons were emitted from the body, which is only one neutron for every 10 billion neutrons in the body, based on an estimated body weight of 170 lb (77.1 kg). This would occur, for example, if only 0.0004% of the deuterium, or heavy hydrogen, atoms in the body were to fission. Deuterium is of special interest because it requires the least energy input to fission. This would release enough neutrons to shift the carbon date from 33 AD to 1260–1390 AD and approximately enough protons to produce the images, according to experiments of proton irradiation on linen (Lind 1989).

This neutron absorption hypothesis is the best concept to explain the carbon dating of the Shroud to 1260–1390 AD because it is the only hypothesis consistent with the four things we know to be true about carbon dating as it relates to the Shroud:

The uncorrected carbon date at the 1988 sample location is 1260 ± 31.

The slope or gradient to the carbon dates is about 36 years per centimeter of distance from the bottom of the cloth.

The carbon dates for the subsamples are in the range of 1155 to 1410 AD.

The Sudarium of Oviedo is an 84 × 53 cm linen cloth that has been in the cathedral in Oviedo Spain since 1113 AD. It contains no image but does contain blood stains similar to the Shroud of Turin. Ancient tradition claims the Sudarium is Jesus’s face cloth mentioned in John 20:7 and thus is connected to the Shroud of Turin. Historical documents state it left Palestine prior to 614 AD. It was carbon dated to about 670 AD.

Using this hypothesis of neutrons homogeneously emitted from the body as it lay in a limestone tomb, a long series of MCNP nuclear analysis computer calculations were run. MCNP is an acronym for Monte Carlo N-Particle, where “N” stands for neutron. MCNP was developed at the Los Alamos National Laboratory over many decades and is approved by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for nuclear analysis for a variety of purposes.

Figure 7 shows some of the results of these MCNP calculations. The vertical axis on this figure shows the carbon date calculated by MCNP for a location along the midline (backbone) of the body on the cloth under the body (on the dorsal image). The calculated carbon dates are quite variable, with about 90% of the locations dating to the future when the standard equations are used to calculate the date. A carbon date to the future is calculated when there is a higher C-14/C-12 ratio in a sample than is present in our environment.

The second point from the left in Figure 7 is approximately where the samples were cut from the Shroud in 1988 for carbon dating. The MCNP-calculated slope at this point agrees with the experimental slope, about 36 years per centimeter in Figure 6, obtained from carbon dating measurements at the three laboratories. The results of the MCNP calculations appear to have also received independent confirmation from the position dependence of the fluorescence on the Shroud (McAvoy 2021) based on photos taken by STURP in 1978.

Mystery #3: Blood

The third mystery is related to the blood. About a dozen tests have been performed on the blood. The results of these tests proved that what appears to be blood is blood. All results are also consistent with it being human blood, though further testing is needed to exclude other possible options. Blood could have drained from the body onto the cloth where there were wounds in the scalp, wrists, side, and feet. However, the problem is explaining how the blood—which would have dried on the skin—could have transferred to the cloth. Examples are the blood that drained from the wrist wounds and ran down the arms, and the blood from the scourging.

Since dried blood does not absorb into cloth, why is the blood that would have dried on the body now on the cloth? The hypothesis of an extremely brief intense burst of radiation emitted in the body offers a possible explanation. If the radiation burst was sufficiently brief and sufficiently intense, it would thrust wet or dried blood off the body onto the cloth by a natural process called radiation pressure. This is a process by which radiation transfers momentum to an object, which causes it to move. But the radiation would have to be particle radiation.

Discussion

A hypothesis has been discussed as a possible explanation for three of the most significant mysteries of the Shroud. This hypothesis proposes that an extremely brief intense burst of radiation from the body produced heating and/or ozone that discolored the fibers to form the images of a crucified man. This burst of radiation included neutrons that produced new C-14 in the fibers, which shifted the carbon date forward from the time of Jesus, about 33 AD, to 1260–1390 AD. If it was brief enough and intense enough, the radiation burst could have thrust the dried blood off the body onto the cloth by a natural process called radiation pressure.

The most important questions regarding the Shroud of Turin are whether it could be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus Christ and whether the images could have been encoded onto the cloth by a burst of radiation emitted from his dead body. If the evidence indicates these questions should be answered in the affirmative, then the implications for all humanity could be extremely significant. The importance of these questions should compel us to do our very best scientific research on the Shroud, and to take advantage of every opportunity to do this research.

There is no known example of a human body, dead or alive, producing an image of itself on a piece of cloth, except for the Shroud of Turin. In our current understanding of physics, there is no mechanism or process that can do this. Yet, in the Shroud, there is evidence that a dead human body produced front and dorsal images of itself on linen cloth. From the perspective of science, this unique encoding event appears to require a unique process or mechanism that is outside or beyond our current understanding of physics. Thus, to help humanity gain a more complete and accurate understanding of reality, further scientific testing should be performed. There is a possibility for significant scientific research to be performed on the Shroud following the rumored exhibition of the Shroud in 2025. Every effort should be made to prepare a testing program to take advantage of this possibility.

*In statistical analysis, the average value of a series of measurements is called the “mean.” The uncertainty associated with this mean value can be illustrated by a Gaussian distribution, which is also called a bell curve. This curve plots the probability of how close the true value should be to the mean value, which is at the peak of the bell curve. The uncertainty of the mean value, and thus the width of the bell curve, is expressed in a calculated value known as the standard deviation. The symbol used for the standard deviation is the Greek letter sigma (σ), so that an uncertainty of one standard deviation is called a one sigma uncertainty. The mean value plus or minus one sigma (one standard deviation) should have about a 68% probability of having the true value within this range. The mean value plus or minus two sigma (two standard deviations) should have about a 95% probability of having the true value within this range. The mean value plus or minus three sigma (three standard deviations) should have about a 99% probability of having the true value within this range. However, these probability values depend on the number of measurements that were made to determine the values for the mean and standard deviation.

_______

Robert (Bob) A. Rucker: MS, Nuclear Engineering, University of Michigan, robertarucker@yahoo.com.

Acknowledgments

This article, as it appears in Materials Evaluation, was reviewed for accuracy by Arthur C. Lind, PhD (physics) and Mark Antonacci, JD. Figures 1 and 3 are reproduced courtesy of the Barrie M. Schwortz Collection, STERA Inc.

Citation

Materials Evaluation 80 (2): 24–36 https://doi.org/10.32548/2022.me-02022 ©2022 American Society for Nondestructive Testing

References

Casabianca, T., E. Marinelli, G. Pernagallo, and B. Torrisi, 2019, “Radiocarbon Dating of the Turin Shroud: New Evidence from Raw Data,” Archaeometry, Vol. 61, No. 5, pp. 1223–1231, https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12467

Damon, P.E., D.J. Donahue, B.H. Gore, A.L. Hatheway, A.J.T. Jull, T.W. Linick, P.J. Sercel, L.J. Toolin, C.R. Bronk, E.T. Hall, R.E.M. Hedges, R. Housley, I.A. Law, C. Perry, G. Bonani, S. Trumbore, W. Woelfli, J.C. Ambers, S.G.E. Bowman, M.N. Leese, and M.S. Tite, 1989, “Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin,” Nature, Vol. 337, pp. 611–615

de Figueiredo, L.C., 2015, “Dr. Paolo Di Lazzaro Explains His Research on Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin,” available at https://www.academia.edu/11355553/Dr_Paolo_Di_Lazzaro_explains_his_research_on_image_formation_on_the_Shroud_of_Turin

Di Lazzaro, P., A.C. Atkinson, P. Iacomussi, M. Riani, M. Ricci, and P. Wadhams, 2020, “Statistical and Proactive Analysis of an Inter-Laboratory Comparison: The Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin,” Entropy, Vol. 22, No. 9, p. 926, https://doi.org/10.3390/e22090926

Fanti, G., F. Lattarulo, and O. Scheuermann, 2005, “Evidences for Testing Hypotheses About the Body Image Formation of the Turin Shroud,” The Third Dallas International Conference on the Shroud of Turin, 8–11 September, Dallas, TX

Heller, J., 1984, Report of the Shroud of Turin, Houghton Mifflin Co.

Jackson, J., 1989, “The Vertical Alignment of the Frontal Image,” available at https://www.shroud.com/pdfs/ssi3233part3.pdf

Jackson, J.P., and E.J. Jumper, 1976, “The Three Dimensional Image on Jesus’ Burial Cloth as Revealed by Computer Transformation,” personal correspondence dated 30 July 30, to Peter M. Rinaldi, author of many books on the Shroud. Contact robertarucker@yahoo.com to obtain a copy.

Jackson, J.P., E.J. Jumper, and W.R. Ercoline, 1984, “Correlation of Image Intensity on the Turin Shroud with the 3-D Structure of a Human Body Shape,” Applied Optics, Vol. 23, pp. 2244–2270

Jumper, E.J., 1982, “An Overview of the Testing Performed by the Shroud of Turin Research Project with a Summary of Results,” IEEE Proceedings of the International Conference on Cybernetics and Society

Lind, A.C., 1989, “Image Formation by Protons,” available at https://www.testtheshroud.org/articles

Lind, A.C., M. Antonacci, G. Fanti, D. Elmore, and J.M. Guthrie, 2010, “Production of Radiocarbon by Neutron Radiation on Linen,” available at https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Production-of-Radiocarbon-by-Neutron-Radiation-on-Lind-Antonacci/61ec4a8c6ed72fec1cde5cf124368dc0bf089344

Marino, J.G., and M.S. Benford, 2000, “Evidence for the Skewing of the C-14 Dating of the Shroud of Turin Due to Repairs,” available at https://shroud.com/pdfs/marben.pdf

McAvoy, T., 2021, “On Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin,” International Journal of Archeology, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 34–44, https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ija.20210902.11

Rucker, R.A., 2016, “Information Content on the Shroud of Turin,” Paper 5, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2018, “The Carbon Dating Problem for the Shroud of Turin, Part 2: Statistical Analysis,” Paper 12, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2019, “How the Image Was Formed on the Shroud,” Paper 27, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2020a, “Holistic Solution to the Mysteries of the Shroud of Turin,” Paper 24, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2020b, “Role of Radiation in Image Formation on the Shroud of Turin,” Paper 6, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2020c, “Understanding the 1988 Carbon Dating of the Shroud”, paper 25 on www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Rucker, R.A., 2020d, “Date of the Shroud of Turin,” Paper 29, available at www.shroudresearch.net/research.html

Walsh, B., and L. Schwalbe, 2020, “An Instructive Inter-Laboratory Comparison: The 1988 Radiocarbon Dating of the Shroud of Turin,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, Vol. 29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102015

Walsh, B., and L. Schwalbe, 2021, “On Cleaning Methods and the Raw Radiocarbon Data from the Shroud of Turin,” International Journal of Archeology, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 10–16, https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ija.20210901.12

View the original article here. For more articles like this, subscribe to the ASNT Pulse blog today!

Project Coordinator for Applied Inspection Systems

3moPareidolia

Senior Metallurgical Engineer at SGS - Msi

3moI think some people may be upset about McCrones' microscopic examination results shroud is an art piece - a very good one.

NDT Consultant

4moThis image seems realistic to me.

ATI / Ladish Forge

4moPretty cool

Director @ OOGA Technologies | NDT Coaching, Quality Management, Digital Transformation

4moThis was one of my favorites!