The Mysteries of the Shroud of Turin

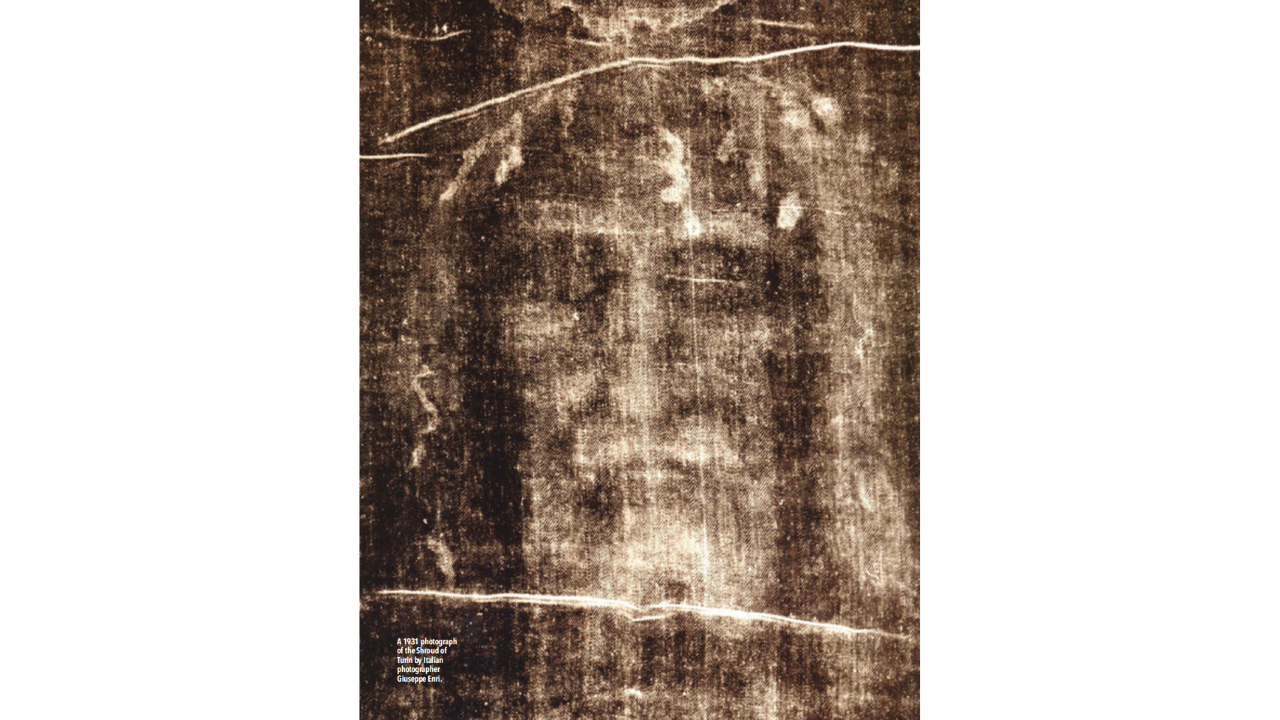

In 1931, a professional photographer named Giuseppe Enri pointed his camera at a piece of cloth called the Shroud of Turin and took the picture shown. How was this image formed? When was it made? Who made it? Is this an image of a real person? Could this be an image of the man known as Jesus Christ? Could this be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus? These are just a few of the questions that arise.

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most mysterious and potentially significant items in human possession. It has been featured on the cover of US News and World Report (1 March 2002) and Time magazine (20 April 1998). The June 1980 edition of National Geographic included a 24-page article with a four-page foldout of the Shroud. In the 1980s, the Shroud was briefly headline news around the world, but for reasons that will be discussed later, the Shroud has received little media attention for the last three decades. That is now starting to change due to four recent papers on statistical analysis published in peer-reviewed journals.

This article provides an overview of the Shroud, including its images, history, materials, and previous testing. It also includes the author’s hypothesis to explain the main mysteries of the Shroud. The purpose of this article is to encourage the development of a program for future testing of the Shroud.

What Is the Shroud of Turin?

A shroud is a piece of cloth in which a person is buried. Turin, also called Torino, is a city in northwestern Italy. Thus, the Shroud of Turin refers to a particular burial cloth that has been in Turin, Italy, since 1578. The Shroud is a linen cloth about 14 ft 4 in. long by 3 ft 8 in. wide (437 × 111 cm). It is about as thick as a T-shirt (about 0.35 mm) and is very pliable. Many people regard this cloth to be a holy relic because ancient tradition has long claimed it to be the authentic burial cloth of Jesus Christ. This claim is supported by the full-size front and dorsal (back) images of a man who was crucified exactly as Jesus was crucified according to the Gospels in the New Testament, yet extensive testing in 1978 indicated these images are not due to pigment, scorch, liquid, or photography.

What Do the Images Show?

In Figure 1, the top image shows the Shroud as it would normally be seen. It shows two long scorch marks caused by a fire in 1532 when it was in Chambery, France. Also shown are water stains resulting from water thrown onto the box containing the Shroud after the fire and 16 patches used to repair one burned corner of the Shroud, as it was folded in the box. The images of the crucified man can be seen between the scorch marks. The front image is on the left with head, arms, torso, and legs visible. The back (or dorsal) image is on the right, with the head toward the left and the feet on the right.

The bottom image in Figure 1 is the photographic negative of the Shroud, but it shows the body as a positive image. This means the images on the Shroud are negative images, with light and dark areas reversed. It is important to note there are no images of the sides of the body or the top of the head, and the front and dorsal images are head-to-head.

Vertical views of the images are shown in Figure 2. The front image shows puncture wounds in the scalp as would occur from a cap (crown) of thorns. It shows a swollen cheek, bent nose, and a 2 in. elliptical wound in the side the size of a Roman thrusting spear, with blood running down from it separated into red and clear components. The clear components contain blood plasma and clear watery fluid from the pleural cavity. This indicates the side wound is a postmortem (after death) wound.

The front image shows a nail wound through the wrist, contrary to paintings in the Middle Ages depicting crucifixion, which had the nails going through the palm. We now know a nail through the palm would not support sufficient weight because it would have no bones above it. The image does not show the thumbs, also contrary to paintings of the Middle Ages. When the nail was forced through the wrist at that location, it would have crushed the nerve that passes through that location. All the nerves from the fingers and the thumb connect into this nerve, so that crushing it would have forced the thumb to collapse into the palm. Thus, in both respects (location of the nail wound and no thumbs visible), the image indicates it was not made in the Middle Ages, contrary to the 1260–1390 AD carbon dating of the Shroud.

The front image also shows blood that ran down the arms from the wrist wounds, with two angles of the blood flow consistent with a man pushing up and down on the cross to breathe. About 120 scourge marks are visible as well as abrasions on the nose and one knee, suggesting the man had one or more falls. There is also a 3.2 in. wide side strip sewn onto the main Shroud using a unique professional stitch most similar to a stitch on a cloth from Masada, which was destroyed in 73–74 AD. This indicates the Shroud is probably from the first century.

The dorsal image in Figure 2 shows puncture wounds in the scalp and abrasions on the shoulders consistent with carrying a rough heavy object. Scourge marks are visible down the body consistent with two Roman flagra (scourge whip) containing dumbbell shaped weights on the ends of three straps, along with a flow of blood and clear blood serum and clear watery fluid from the pleural cavity that drained from the side wound and ran across the small of the man’s back. Also, two nails were evidently placed through one foot with only one of the nails through the other foot. This would permit one foot to be rotated to allow the man to push up and down to breathe while crucified. The shape of the feet, being twisted together, indicates the presence of rigor mortis. This indicates the man was dead on the cross long enough for rigor mortis to set in.

There are several unusual or unique features to the images on the Shroud. The images are negative on the cloth with light and dark areas reversed. They have no outline or brush strokes, and they contain 3D information (Jackson et al. 1984), which allows a 3D statue to be reconstructed from the 2D Shroud. No painting or photograph contains 3D information. Also, the Shroud contains no products of body decay. The front and dorsal images are head-to-head because the cloth was wrapped up the back of the body, over the head, and then down the front of the body.

A closer view of the face is shown on the opening photo in a positive image. This image contains an exact front view with long nose, mustache, beard, and hair parted in the middle coming down on both sides of the head, with the hair a little longer on one side than the other. This image appeared in paintings starting about 550 AD and was on coins starting about 692 AD. Thus, this image long predates the carbon dating of the Shroud (1260–1390 AD) and is the source of our concept of Jesus’s appearance.

Continue reading this article here. For more articles like this, subscribe to the ASNT Pulse blog today!

Quality Mgr. / welding engineer at Brink's Welding & Fabrication

1yReally appreciate this article as it clearly and concisely provide factual information

Director Sales & Marketing at Phoenix National Laboratories

1yWow this is an amazing example of the historical application of NDT-how absolutely fascinating!