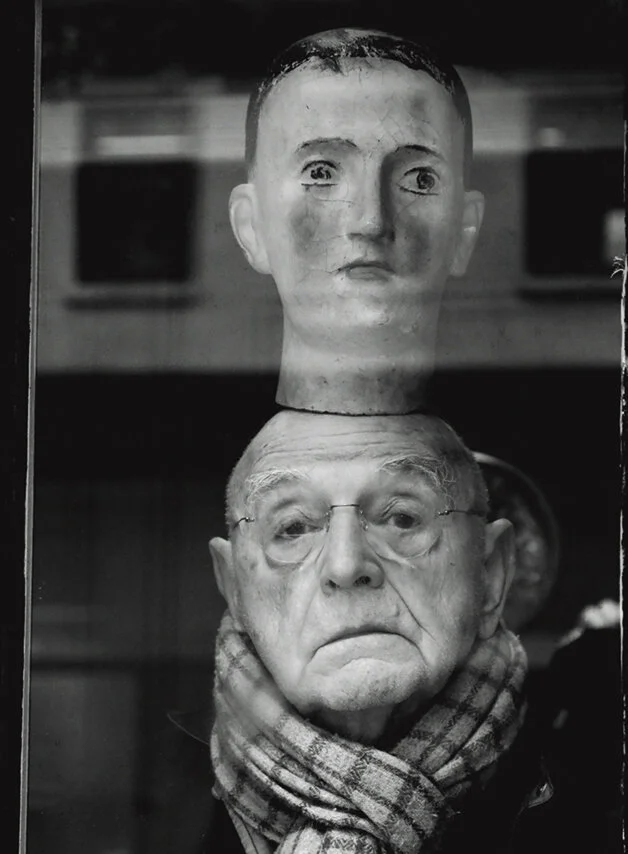

Duane Michals

Interview & Photography & by Mart Engelen

Duane Michals, New York 2018

A conversation in New York about his life and work with influential American photographer Duane Michals, who is noted for his innovative use of narrative photo-sequences, which often incorporate handwritten texts, to examine and express emotion and philosophy.

Mart Engelen: When did you start to take pictures?

Duane Michals: Hmm, it was by accident. I went to Russia when I was 26. That was in 1958 and I borrowed a camera. Actually, what happened was that I was working at Life Magazine doing promotion. Let me back up. I came to New York because I love books and magazines and I wanted to be involved somehow in publishing but I didn’t know what. So I ended up working at Life Magazine doing promotion, advertising. And while I was there, I discovered you could go to Russia. It was the height of the Cold War and we were not talking to the Russians. It cost a thousand dollars to go there. I was making a hundred dollars a week so that was 20% of my income. I borrowed five hundred dollars from my parents and I ate sandwiches for six months. Then I borrowed a camera. I had taken one photo course earlierbutthatwasnothing.Myfriendsaid.“Youtakethiscamera(itwasa13dollar camera) and put this thing in front, the shutter, on 500 and this thing on top, the diaphragm, on 16 when you are outside and on 2.8 when you are inside.” That’s how I got started. And I knew how to say “May I take your picture?” in Russian.

ME: And what were you actually doing in Russia?

DM: I was a ‘flaneur’. I was walking around and taking pictures.

ME: So you were not there working for anybody or anything? So you just saved your money and wanted to see Russia.

DM: Yes, it was a great adventure. I had always loved the idea of adventures. Talking to you is an adventure. A scary adventure. (Laughs)

ME: Well, we don’t know yet. (Laughs)

DM: But, for example, when I was 14, I went to Texas. I read in the papers you could get a job on the wheat crop. And it was an huge adventure. Disastrous and fabulous. So I always have the notion of adventure. I see my life as an adventure and I am the hero of my story.

ME: What actually inspired you to do pictures then and today?

DM: I took pictures then because it seemed to be obligatory. You go on a trip and you take pictures. I was going to Russia. You take pictures when you travel. There was no destination for the photographs. There was no ambition. But the trip changed my life because after I came back, about a year later, I just declared I was a photographer although I had no…

ME: Education?…

DM: No. Education was a disaster.

ME: You were self-taught?

DM: Yes, but I had somebody help me. I gave a graduation talk at the News School and asked the students what it cost them to go to school here? They told me two hundred thousand dollars. Are you crazy! Get out there and take pictures! I learned everything on a job and I’m still learning!

ME: Exactly. Then came a moment when you decided to write and paint on your photographs. Can you tell me more about that?

DM: Luckily, not having gone to photo school, I never learned the photo rules. So in the 1960s I began to take photographs. The paradigm, the definition, of photography, was you walked down the street and you took pictures. A photographer is a good observer and if you are really lucky you get the decisive moment. But it takes you 3,000 photographs to get that moment. That didn’t interest me because my interests—my heroes—were De Chirico, Magritte and Balthus. So that was where my mind was and I am a big reader and so it would never have occurred to me. Well the principle was, I am not Ansel Adams so why should my photographs look like his? I am not Gary Winogrand. Oh, I love Robert Frank, he’s my favourite photographer.

ME: When you started with photography, like you said, all these photographers who worked for Magnum were indeed occupied with trying to get the decisive moment. But you were not interested in that kind of photography.

DM: Exactly. I was interested in storytelling.

ME: Already at an early stage?

DM: Yes. I started by doing portraits. I am very good portrait photographer. My take on portraiture is quiet different than the average take. I have four types of portraits. ME: Four types?

DM: My first type I call stand and stare, the second I call annotated portrait. So I did a portrait of my father, brother and my mother and then I wrote underneath. I got to writing on photographs because I was frustrated with the lies of photographs. It wasn’t enough to express. I abandoned photography as a thing in itself. It was not enough. I annotated, I wrote with photography because photography fails. Now, if I take a picture of you and I know nothing about you, I would see an interesting- looking man.

ME: You make your own truth.

DM: Well, what I do is, if I took a photograph of my mother, father and my brother: let’s say my mother and my father when they were old, standing and smiling in front of my camera. They haven’t made love in forty years, they didn’t even like each other. The photograph would not tell you he was an alcoholic. The photograph would not tell you my mother had an affair with somebody else. That’s bullshit. Real bullshit!

ME: It would be a phony picture.

DM: They are all phony pictures. [Looks at the cover of the new # 59 Magazine.] What do I know about her? If you hadn’t told me that is your wife and that she is French, she could be from California.

ME: Right. One photographer, I don’t remember who, said, “The best photographer is the best liar” and I remember Avedon said, “Every portrait is a subjective interpretation by the maker.” So, indeed it’s probably quite arrogant to think that when a photographer makes a portrait it says something about that person. But then again everything is in the eye of the beholder. (Laughs).

DM: Absolutely. So I began to write with photographs and so the writing came out of frustration. The next kind type 3 is the imaginary portrait. [Duane shows a self-portrait.] I am sitting and looking in a book and in the book I wrote “I think about thinking”. So what’s interesting about me is not my face who cares what I look like it’s my imagination. So this says more about me than any picture of me staring at the camera.

ME: We can also say that death is a theme in your work. It always comes back. DM: Always and now that I am closer to death, it’s bigger than ever.

ME: Do you consider photography nowadays as art? So many people today call themselves artist, curator, whatever. How do you regard this development?

DM: I hate the word art. I think it was Goebbels or Goering who said, “When I hear the word art, I reach for my revolver.” (Laughs). Here, by the way, you see my imaginary portrait of Marlene Dietrich as Demoiselle d’Avignon.

ME: What I like about your work is the reference with history, with the subject, because so many people just click and click. There is no content.

DM: Gary Winogrand left about 5,000 rolls of film that he never developed. He said he liked the act of taking a picture but was not interested in the photograph. He took a picture of everything that moves. I only pick up a camera when I have a reason to. I love to do commercial work too, it’s because it’s all in my imagination. I don’t have to go to Africa to photograph people—somebody I know nothing about. That’s description. This is important to become, I am not going to use the word, an artist, but the photographer must bring insight into what he is photographing. ME: What exactly do you mean by description?

DM: When I take a picture of your face, I show your face. That’s description. I once wrote about my face. I said how the geography of my face was changing and all the lines that had been streams were becoming rivers. And how my whole face is like a glacier moving slowly down home, the earth. Photographers never think, they only look. A writer comes to an empty piece of paper and everything that goes on that paper, he invents. A painter comes to an empty canvas and everything he puts on the canvas, he invents. Only a photographer goes out looking for things that already exist. He never invents anything. He doesn’t create.

ME: Is a photographer an artist? I think it depends on the photographer.

DM: That’s true.

ME: We don’t have to go on with the story of how you regard today’s phenomenon of social media in relationship to art because we’ve actually covered it already. DM: No, I hate it.

ME: You said in an earlier interview, “I love intimacy, everything else is noise”. So how do you think truth, honesty and real intimacy should be expressed in a photograph?

DM: [Takes his own book ABC Duane and quotes from the chapter on Intimacy.] “We seemed to be standing in the wings, waiting for our chance at last to go on. Our conversation had become a rehearsal of familiarity. I don’t remember which particular word in our script opened the door that had been closed. Now silence betrayed an unspoken touch. The vacuum that created a distance between us began to fill with palpable intensity. We stopped acting…”. I would find the concept of intimacy easier to describe in text. For me, the keyword is expression. I am a expressionist. It’s not about being a photographer, it’s not about writing; it’s about whatever you need to express. The camera is just another tool like a typewriter.

Copyright 2018 Mart Engelen

Duane Michals, New York 2018

Duane Michals, New York 2018