“Though this be madness, yet there is method in ‘t,” Polonius says in Act 2 of Shakespeare’s Hamlet after an exchange with the title character. After encountering the unique sculpture of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, first at the Belvedere Palace in Vienna and recently at Slovak National Gallery Bratislava, I can’t help but feel the same way.

So what do we know about the man behind this extraordinary body of work and are these an early example of the now ubiquitous “selfies”? Messerschmidt was born in 1736 in the village of Wiesenteig, which is now in present day southern Germany. He learned his trade from two uncles, a court sculptor in Munich, and an artist based in Graz, Austria. He studied at the Viennese Academy of Fine Arts and his talent for working in stone and metal soon brought him commissions from the aristocracy and imperial clients. His work at this time reflects the prevailing late Baroque-Rococo style, emphasizing the decorative. Later after travelling to Rome, Paris, and London and observing the work of other sculptors he made the shift toward Neoclassicism, a much more spare and refined style of sculpture. From here on he began to emphasize the features and character of his commissions. By 1769, Messerschmidt was teaching at the Viennese Academy and had established his own workshop. But it seems that all was not well despite these outward signs of success, colleagues and friends observed changes in his behavior. Somewhere between 1770 and 1772 he began work on his character heads.

“In 1771 there must have been a strange rupture in Messerschmidt’s life,” Maria Pötzl-Malikova writes, “to which those around him reacted with rejection: there were no commissions and the artist became isolated.” Where once Maria Theresa of Austria, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, and even Franz Anton Mesmer stood for sculpted portraits, such opportunities disappeared along with, apparently, Messerschmidt’s sanity.

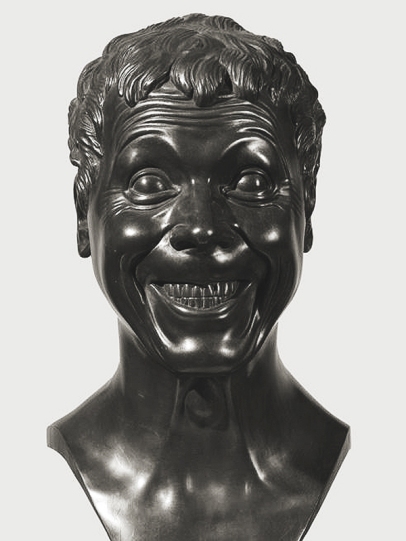

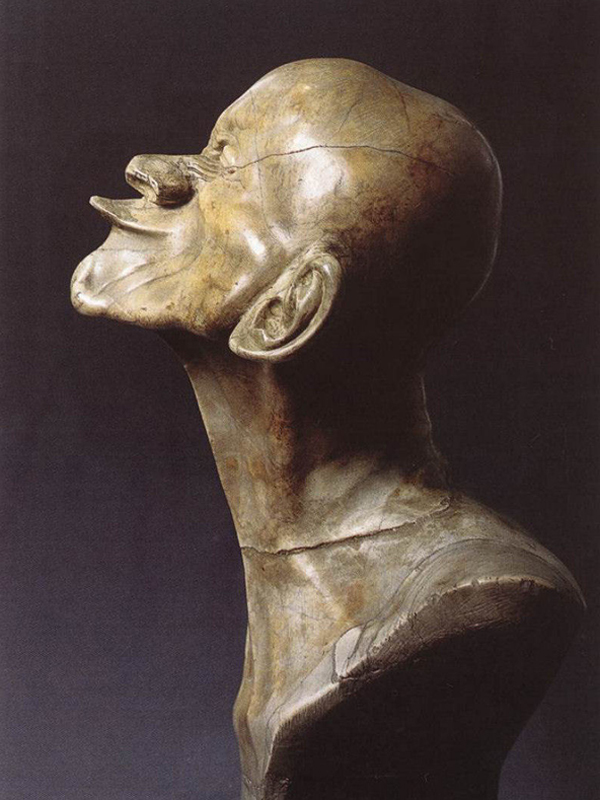

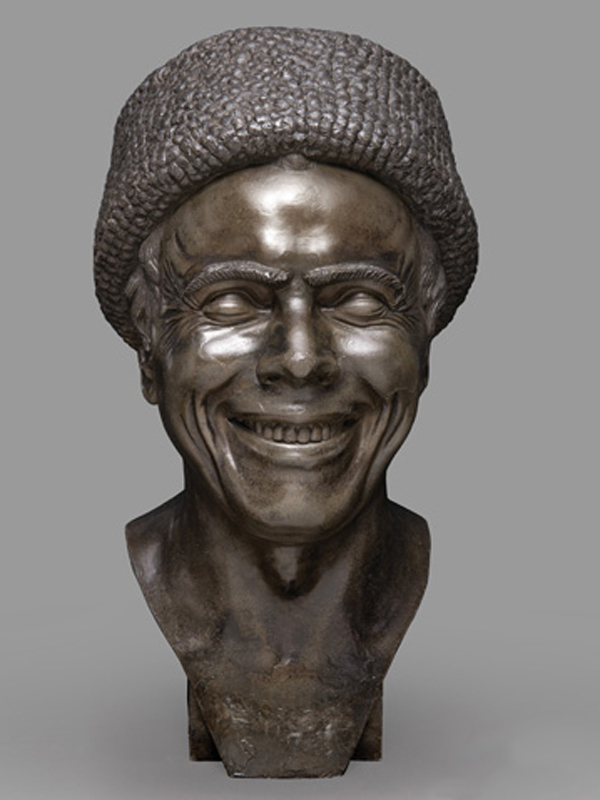

In his isolation, Messerschmidt began sculpting a series of works known after his death as “character heads.” “In Messerschmidt’s view,” Pötzl-Malikova explains, “proportions controlled the entire world and also influenced one another.” By distorting the proportions of his own face, which he studied in a mirror as he sculpted each work, “he believed that he could thus alter the proportions of his face in a way that would enable him to master the spirits torturing him.” Each sculpture thus “preserved the magical effect of his grimaces and protected their creator from overpowering dangers.” Messerschmidt’s magic realism born of his amazing technique fulfilled a real (for him) life or death purpose”.

It has been argued (notably by Ernst Kris) that this series of sculptures were connected with certain paranoid ideas and hallucinations from which, at the beginning of the seventies, he began to suffer. Messerschmidt found himself increasingly at odds with his milieu.

His situation worsened to such an extent, that in 1774, when he applied for the newly-vacant office of a leading professor at the Academy, where he had been teaching since 1769, instead of getting it he was expelled from teaching. In a letter to the Empress, Count Kaunitz praised Messerschmidt’s abilities, but suggested that the nature of his illness (referred to as a “confusion in the head”) would make such an appointment detrimental to the institution.

Embittered after failing to gain the professorship position at the academy, Messerschmidt left Vienna and returned to his native Wiesensteig and in the same year, following an invitation, he moved to Munich.

Here he waited two years for a promised commission and for a permanent employment at the Court. In 1777 he went to Pressburg , now modern day Bratislava, where his brother, Johann Adam worked as a sculptor. Here he spent the last six years of his life almost in retirement, on the outskirts of the town. He dedicated himself primarily to his character heads.

He produced the life-sized busts rapidly, 69 within a 13-year period.

He may have intended them as physiognomic studies, perhaps inspired by experiments enacted by his friend, the controversial physician Franz Anton Mesmer. Messerschmidt probably also knew of Johann Caspar Lavater, who popularized “physiognomy”–the notion that human character is discernable by a person’s physical appearance.

In 1781, German author Friedrich Nicolai visited Messerschmidt at his studio in Pressburg and later published a transcript of their conversation.  Nicolai’s account of the meeting is a valuable resource, as it is the only contemporary document that details Messerschmidt’s reasoning behind the execution of his character heads. It appears that for many years Messerschmidt had been suffering from an undiagnosed digestive complaint, now believed to be Crohn’s disease, which caused him considerable discomfort. In order to focus his thoughts away from his condition, Messerschmidt devised a series of pinches he administered to his right lower rib. Observing the resulting facial expressions in a mirror, Messerschmidt then set about recording them in marble and bronze. His intention, he told Nicolai, was to represent the 64 “canonical grimaces” of the human face using himself as a template.

Nicolai’s account of the meeting is a valuable resource, as it is the only contemporary document that details Messerschmidt’s reasoning behind the execution of his character heads. It appears that for many years Messerschmidt had been suffering from an undiagnosed digestive complaint, now believed to be Crohn’s disease, which caused him considerable discomfort. In order to focus his thoughts away from his condition, Messerschmidt devised a series of pinches he administered to his right lower rib. Observing the resulting facial expressions in a mirror, Messerschmidt then set about recording them in marble and bronze. His intention, he told Nicolai, was to represent the 64 “canonical grimaces” of the human face using himself as a template.

During the course of the discussion, Messerschmidt went on to explain his interest in necromancy and the arcane, and how this also inspired his character heads.

Messerschmidt was a keen disciple of Hermes Trismegistus (Nicolai noted that among the few possessions that littered Messerschmidt’s workshop was a copy of an illustration featuring Trismegistus) and abided by his teachings regarding the pursuit of “universal balance”: a forerunner to the principles of the Golden Ratio.

As a result, Messerschmidt claimed that his character heads had aroused the anger of “the Spirit of Proportion”, an ancient being who safe-guarded this knowledge. The spirit visited him at night, and forced him to endure humiliating tortures. One of Messerschmidt’s most famous heads , the Beaked, was apparently inspired by one of these encounters.

Reminiscent of the tale of the encounter

between William Blake and The Ghost of a Flea.

So what are we to make of this body of work by the once successful portraitist of the nobility and the rich? Did he suffer some kind of breakdown in 1771 that left him reeling.

Did this series of “character heads” modeled after his own appearance serve as talismans against the demons he felt chasing him?

That haunted feeling makes Messerschmidt’s eighteenth-century art seem remarkably modern—a study of demonology that set a precedent for the demons to come in the twentieth century. For me Messerschmidt can be seen in relation to artists such as William Blake, Richard Dadd and Francisco Goya for his explorations of the dark side of the human soul. This work may well be madness but the world is a richer place for its existence.

You know where I can find more about Messerschmidt?

I particulary want to read Friedrich Nicolai talking about him but I just can’t seem to find the source anywhere.

http://www.delarte.com/xFXM2/samplepages.htm

try the link above.

or http://ir.brandeis.edu/bitstream/handle/10192/25350/OlvidoThesis2013.pdf?sequence=4

You can try this one

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2010/09/30/the-heads-of-franz-xaver-messerschmidt/