- Home

- Executive summary

- Territories

- Kisimbosa – DR Congo

- Yogbouo – Guinea

- Fokonolona of Tsiafajavona – Madagascar

- Kawawana – Senegal

- Lake Natron – Tanzania

- Qikiqtaaluk – Canada

- Sarayaku – Ecuador

- Komon Juyub – Guatemala

- Iña Wampisti Nunke – Peru

- Hkolo Tamutaku K’rer – Burma/Myanmar

- Fengshui forests of Qunan – China

- Adawal ki Devbani – India

- Tana’ ulen – Indonesia

- Chahdegal – Iran

- Tsum Valley – Nepal

- Pangasananan – Philippines

- Homórdkarácsonyfalva Közbirtokosság – Romania

- National and regional analyses

- Global analysis

It is estimated that at least 40% of Ecuadorian territory (approximately 104,059.1 km2) are territories of Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubio peoples and nations. In a plurinational and intercultural state, the recognition and guarantee of territorial and collective rights and the rights of nature is an essential path to ensuring biodiversity conservation. Five territories of life have been registered in the World Database of Territories of Life (ICCA Registry), as of April 2021. In total, they cover about 17,906.37 km2 of natural ecosystems (tropical rainforest, dry forest and shrub vegetation), in key areas for biodiversity conservation, under their own forms of governance. Yet, 80.2% of these territories of life are threatened by extractivism.

Context

Ecuador is one of the planet’s megadiverse countries. Located at the crossroads of the Andes Mountains and the equator in South America, it is one of the smallest and most densely populated countries in the region. 45.5% of its surface area is part of the Amazon basin, which is home to the country’s largest areas of tropical forest in good state of conservation. The highland region (Sierra) accounts for 23.6%, the coastal region for 27.5%, and the Galapagos Islands for 3.2%. See Map 1.

In response to the demands of the Indigenous movement and social organizations to recognize the cultural diversity of the country, Ecuador’s Constitution recognizes it as a state of rights, intercultural and plurinational (Art. 1). Peoples, nations, and collectives are rights holders, including Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, and Montubian communities, peoples, and nations (Art. 10, Art. 57 et seq.), and nature is also a rights holder (Arts. 70-74). According to the 2010 census, Ecuador’s total population is 14.4 million, of whom 7.4% self-identify as Montubian, 7.2% as Afro-Ecuadorian, and 7% as Indigenous.[1]

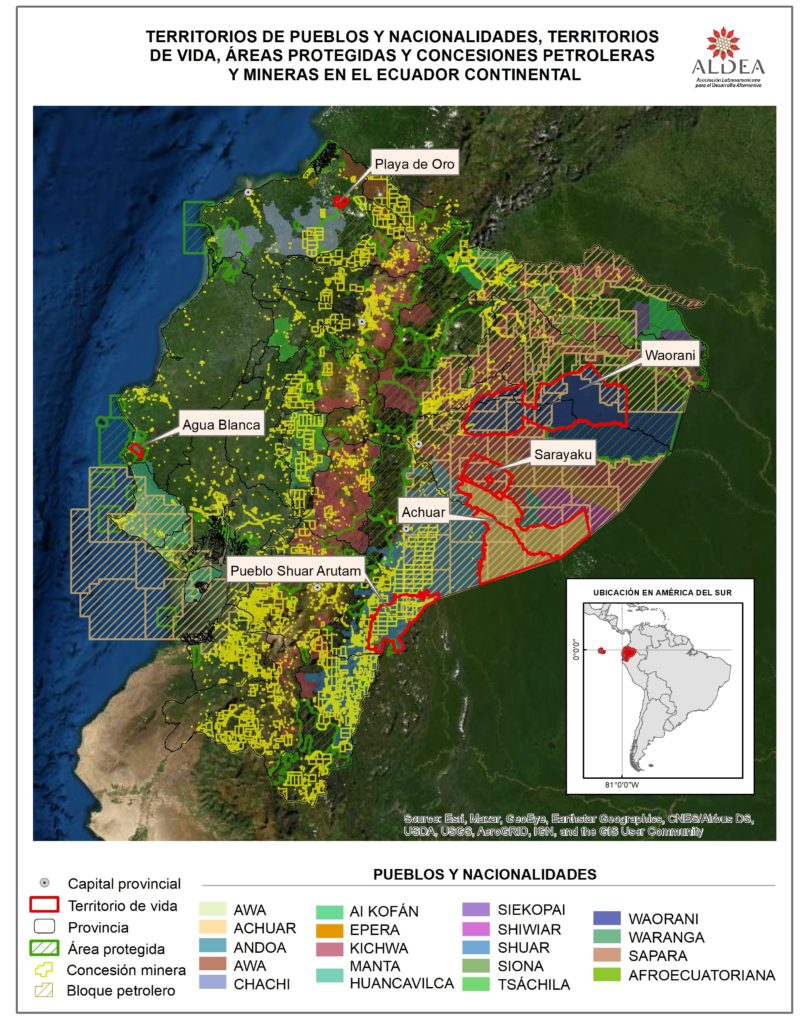

There are Indigenous Peoples living throughout Ecuadorian territory. However, there are regions where they have a prominent presence, for example in the Amazon and the Sierra. In the Amazon, there are the following nations: Achuar, Ai’Kofán, Waorani, Siekopai (also known as Secoya), Quijos, Andwa, Shuar, Siona, Shiwiar, Sapara, and Amazonian Kichwa (comprised of multiple autonomous peoples, including the Kichwa People of Sarayaku). The Amazon region is also home to the Tagaeri and Taromenane Indigenous peoples in isolation,[2] or “peoples in voluntary isolation,” as defined by the Constitution. In the Sierra live the Natabuela, Otavalo, Karanki, Kayambi, Kitu Kara, Panzaleo, Chibuleo, Salasaka, Kispincha, Tomabela, Waranka, Puruhá, Kañari, Saraguro, Paltas, and higland Kichwa. On the coast, there are the Épera, Awá, Chachi, Tsáchila, Manta, Huancavilca, and coastal Kichwa. See Map 2.

Although there is no official national-level mapping, several studies estimate that at least 40% of Ecuadorian territory (104.06 km2) corresponds to the territories of Indigenous Peoples and local communities. The Amazon is the region with the largest area of Indigenous territories, representing 73% of the country’s territories belonging to peoples and nations.

Some Indigenous Peoples were separated by state borders, which affected and continues to affect dynamics of mobility and territorial use. This occurs along the borders with Colombia and Peru. These transboundary peoples include the Awá, Chachi, A’i Kofán, Siona, Siekopai (Secoya), Shuar (in Ecuador, Wampís nation in Peru) and the Achuar in Ecuador and Peru.

The majority of Indigenous communities are affiliated with second-level organizations, that is, provincial and sub-provincial organizations, and these in turn are affiliated with regional organizations such as CONFENIAE[3] in the Amazon, ECUARUNARI[4] in the Sierra, and CONAICE[5] on the Coast. These are in turn affiliated with a national organization, CONAIE,[6] the largest Indigenous organization in Ecuador. Other national Indigenous organizations are FENOCIN[7] and FEINE.[8] At the supranational level there are two relevant organizations: COICA,[9] which brings together the Indigenous organizations of the nine Amazonian countries, and CAOI,[10] which is comprised of the organizations of the Andean countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia).

Territories of life, protected areas and extractivism

Biodiversity is important to Ecuador and is protected in the Constitution, which recognizes the rights of nature. Ecuador has ratified and been a “party” to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) since 1993, which commits it to meeting the Aichi Targets and the National Biodiversity Targets. In terms of protected areas, approximately 20%[11] of the country’s land area (continental and insular) is part of the National System of Protected Areas (SNAP), which seeks to guarantee biodiversity conservation and the maintenance of ecological functions.[12] Although the SNAP is made up of four subsystems—state, decentralized autonomous, private and community—the latter “is still being structured”.[13] The experiences of co-management and co-administration of protected areas have not yet been able to effectively integrate the territorial dimension and the importance it represents for the peoples and nations, most of whom have a close relationship with their territory that is expressed in their profound knowledge of the forests, paramos and mangroves, as well as in their own knowledge, practices and forms of organization that allow them to recognize and collectively manage their common goods. About 16.4% of the SNAP overlaps with the territories of peoples and nations. Several peoples and nations are demanding recognition of their own governance and conservation systems, such as the Achuar System of Conservation and Ecological Reserves (SACRE), proposed by the Achuar nation, which maintains 95%[14] of their forest in a good state of conservation; the Kawsak Sacha, of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku; or the Kayambi people in the northern Sierra of the country, who have maintained collective agreements for several years for the management and care of the paramos and water resources.

While there are efforts to advance conservation, at the same time, extractivism is advancing. In 2008, Ecuador implemented the Socio Bosque program, a mechanism of economic incentives to individuals, peasant communities, peoples and nations to conserve forests, paramos, and other fragile ecosystems. According to the Ministry of Environment and Water, by 2018, the total area of the Socio Bosque program reached 1.616 million hectares.[15] Some of these areas compensated for conservation are at the same time concessioned for oil and mining activities. One of the most extreme examples of this contradiction is the case of the territory of the Shuar Arutam People (PSHA), where 41% of its surface area is in the Socio Bosque program and, at the same time, 76% has been concessioned for mining and oil activities.[16] This shows the dispute over and pressure on Indigenous territories: on the one hand, a developmentalist model based on extractive activities and, on the other, a proposal for self-determination, territorial defense, and conservation of nature through community governments.

In addition to this, there is an explicit vision of protected areas as “reserve zones for future extractivism.” Since their creation, National Parks (a category within the SNAP) are not susceptible to exploitation. Despite this, Yasuní National Park (YNP), which was one of the country’s first parks, has had its boundaries modified several times to adjust to the demands of oil exploitation, despite being part of traditional Waorani territory (a recently-contacted nation) and of the Tagaeri and Taromenane peoples in isolation.

In 2008, the Constitution extended intangibility to all protected areas and intangible zones, except for in the exceptional case of “national interest,” alleged by the Executive and authorized by the National Assembly. In 2013, the Assembly authorized exploitation in blocks 31 and 43 within Yasuní National Park. In this way, the state in practice treats protected areas and the territories of life of Indigenous Peoples and nations as zones reserved for future extractivism. Protected areas are state creations subject to objectives and regulations that do not always coincide with those of the communities and sometimes even contradict them, that is, they are spaces without democratic and localized governance systems. Therefore, strengthening local communities through an interpretation that guarantees rights to participation could be an appropriate way to enact a different vision of the SNAP and its subsystems.

Recognition of collective rights guarantees, among other rights, peoples’ exercise of autonomy and self-determination, in addition to the right to territory and the right to maintain their own forms of organization, conflict resolution, and Indigenous justice. Yet, all of these forms of recognition have not yet permeated the structure of a state that maintains its hegemonic, racist, patriarchal, and colonial vision. The Ecuadorian economy depends on the extraction of raw materials, which in many cases implies dispossession, displacement and invisibilization of the socio-ecological and cultural diversity of the country. High-impact activities in the territories, such as mining, oil, agribusiness, real estate expansion, among others, have not followed the processes of free, prior and informed consultation (FPIC) provided for in the Constitution. As a result, the affected peoples have not had the opportunity to express, condition, or deny their consent for these activities, which is why, in some cases, they have resorted to the judicial system to sue for non-compliance, as will be explained later in this text.

Ironically, parallel to the recognition of the Ecuadorian state as plurinational and intercultural, over the course of the last 15 years the extractivist model has been consolidated. As can be seen in Map 3, approximately 37.5% of the national continental territory and more than 60% of the territories of peoples and nations are concessioned for mining and oil activities. Extractivism is concentrated in areas of high biodiversity, in the headwaters of watersheds and in areas where impacts transcend national borders. For example, mining concessions increased from 0.04% of the territory in 2004 to 9.5% in 2019.

The Playa de Oro commune is a Territory of Life. Video, 1:55 min, Fundación ALDEA, 2019.

As of April 2021, the territories of life registered in the World Database (ICCA Registry) are located on the Coast and in the Amazon. On the coast are the Playa de Oro community (106.09 km2) and the Agua Blanca community (92.02 km2); in the Amazon region are the Shuar Arutam People (2,325.34 km2), the Waorani Nation of Ecuador (7,744.88 km2), the Kichwa People of Sarayaku (1,350 km2) and, in the process of registration, the Achuar Nation of Ecuador (6,779.30 km2). Together, all of these territories of life possess approximately 17,906.4 km2 of tropical forests, dry forests, shrub vegetation, and other fragile ecosystems in Ecuador. With the exception of the Agua Blanca community (which is located within Machalilla National Park), the territories of life are not part of the SNAP.

Recognition and registration as territories of life arises from a process of self-empowerment, informing, and internal discussions, to recognize the strong link between the population and its territory, and the existence of a self-organizing governance structure that makes decisions to implement their life plans. As a result, nature is maintained in a good state of conservation. Territories of life are the expression of the self-determined effort of peoples and nations to manage their territories, culture, and life, even as 80% of the surface area of these territories of life are affected by mining and oil concessions.

The Agua Blanca Commune is a Territory of Life. Video, 2 min., Fundación ALDEA, 2019.

National legal and policy context

Undoubtedly, the declaration of a plurinational and intercultural state is positive for the peoples and nations, and also for territories of life in Ecuador. With plurinationality, the recognition of the collective territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and nations, Afro-Ecuadorian people, and Montubio peoples has important political potential. The collective rights of peoples are not simply a derivative application of individual rights in the liberal understanding, but spaces to build from perspectives that are parallel to, and even adversarial to, the status quo.

Article 57 of the Constitution recognizes (Indigenous and by extension since 2008, Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubian) collective property as something distinct and differentiated from classic individual property. It recognizes a particular relationship between peoples and territories that manifests itself in a profound interdependence and a deep sense of responsibility of the peoples towards those territories. The constitutional recognition of this relationship is revealed in the fact that the territorial rights of peoples comprise much more than the right to be owners, like any other private owner. Territorial rights give rise to greater safeguards for use, and enjoyment of full ownership. They guarantee imprescriptibility, inalienability, and indivisibility, as well as governance systems, thus guaranteeing recognition of the special relationship between peoples and their territories.

In fact, territorial rights are broad in scope. They include ancestral possession as equivalent to full ownership (Art. 57.5). This is fundamental for at least four reasons: first, because the titling of ancestral territories does not convert those predating the Ecuadorian state into “property” but simply recognizes them; second, because in practice such titling becomes impossible when the state demands the fulfilment of the ordinary legal requirements for any other civil possessor; third, because the collective property of the communities, peoples, and nations is imprescriptible, unseizable, inalienable, and indivisible (Art. 57.4); and fourth, because the possession or ownership of ancestral territories grants communities status as an “ancestral form of territorial organization” (Art. 60).

Furthermore, territorial rights provide peoples with the physical and spiritual space necessary for the maintenance of their identity, ancestral traditions, and social organization (Art. 57.1), the generation and exercise of their own authority (Art. 57.9), and the maintenance, development, and application of their own laws (Art. 57.10). They even allow for the possibility of establishing territorial subdivisions (circunscripciones), within the framework of the political-administrative order of Ecuador, expressly for the preservation of culture (Art. 60).

It is in the peoples’ territories that their biodiversity and environmental management practices (Art. 57.8); their knowledge, science, and technologies, including medicines and traditional medical practices; and their knowledge of the resources and properties of the flora and fauna (Art. 57.12), are developed and expanded. For all of this, it is necessary to conserve the genetic resources of biological diversity and agrobiodiversity: plants, animals, minerals and ecosystems (Art. 57.12).

It is because of this special protected relationship that it is expressly prohibited to displace peoples from their ancestral territories (Art. 57.11) and that they have the right to recover and protect their ritual and sacred sites (Art. 57.12). In addition, in recognition of the history of violence, military activities are expressly limited in the territories (Art. 57.20). In the case of peoples in isolation, their territories (which are their lives) are expressly forbidden for extractivism due to the possibilities of forced or voluntary contact (Art. 57, penultimate paragraph unnumbered).

From a more instrumental point of view, but no less substantial, territorial rights require, in particular, the exercise of participation rights in the specific and strategic state decisions that might affect them. Expressly, they apply to the management of renewable natural resources within their territories (Arts. 57.6 and 57.8) via prior, free and informed consultation. These range from strategic decisions on plans and programmes, to decisions on the possible carrying out of activities in phases. (Art. 57.7). Expressly, and also by prior consultation, the peoples must participate in legislative measures that might affect them (Art. 57.17) and they also have the right to participate in specific government bodies, in defining public policies that concern them and in designing and deciding their priorities in state plans and projects (Art. 57.16).

The effectiveness of land rights and participation would shape new territorialities (many of these denied and hidden up until now) and a new democracy; that is the emancipatory potential of plurinationality. However, the practice is far from this potential. The territories remain subject to the fiction that divides the soil from the subsoil, in which the state reserves subsoil resources under the Constitution (Arts. 1 and 408). This subsoil “property” has been used to support a developmentalist ideology, according to which extractivism is imposed. Nothing in the constitutional texts suggests that, of this property, the state has to extract the resources; they only ratify their inalienable ownership over them. In a plurinational state, these resources belong to the whole population, this includes all Indigenous peoples and nationalities, and to those who do not necessarily share the hegemonic vision of economic growth based on extraction from nature. However, the governmental-entrepreneurial vision is that to deny extractive activities in Indigenous peoples’ territories requires a constitutional reform, under the argument that the only areas where it is expressly prohibited to operate are the protected and intangible areas (Art. 407). Given that this prohibition is not expressly extended to Indigenous territories, the official ‘logic’ is that the state cannot refuse resource extraction. Therefore, territoriality in Ecuador remains fundamentally state-run, hegemonic and extractivist in practice.

At the same time, the possibilities of a new intercultural democracy are limited, given the (non) implementation of recognised participatory mechanisms for Indigenous peoples and nationalities. Strategic decisions about the territories are exclusive to the central government, despite mandates for consultation and participation in making these decisions. Indigenous peoples and nationalities do not participate in macro plans and programmes, with their non-hegemonic visions on the use of land and economic development. These decisions are then crystallised as specific projects, in which the real possibility of influencing the decision is also lessened by the developmentalist ideology referred to above. The potential enrichment of managing public affairs with alternative visions through intercultural democratic mechanisms still remains to be seen.

In general, the rights of Indigenous Peoples are far from being defined. In particular, the territories as spaces for the peoples’ relational autonomy still face official mistrust. The objection to “states within the state” is put forward against claims based on the territory, including the right to consent in prior consultations. In this adverse environment, Indigenous peoples are exercising, de facto, their self-determination, their own rights, their own justice systems and their governance. In some cases they face serious obstacles, like the criminalisation of Indigenous judges (recently granted amnesty)[17] and defenders of nature.

In the legal sphere, results have been achieved with differing impacts. Sarayaku is without doubt an emblematic case, because it includes international condemnation of Ecuador by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, for the violation of rights of an Indigenous community. The sentence has not been fully implemented, given that the pentolite has not been removed from the Sarayaku territory. Nor has the secondary legislation been updated with the international standards for prior consultation. Instead, the government even issued a substandard regulation without consultation for hydrocarbon operations. In spite of the above, the sentence has been useful in advancing other cases with lack of proper consultation in the local courts. The A’I Kofán community of Sinangoe obtained a favourable ruling for lack of prior consultation to grant mining concessions in an ancestral territory with no legal title.[18] The Waorani communities of Pastaza won a case for lack of appropriate prior consultation and consent for Indigenous peoples in recent contact in the establishment of an oil block.[19] This sentence enabled other Amazonian communities to argue the invalidity of the whole of the Eleventh Oil Bidding Round, a state oil expansion plan towards the central-southern Amazon, which was not consulted. In the Piatúa River case, violations of the rights of nature by a hydroelectric project without consultation were acknowledged.[20] In Río Blanco, in the mountains of southern Ecuador, another judicial victory for lack of consultation has not restored the social fabric that was damaged by mining projects without consultation: an anti-mining leader was recently killed in an incident with a pro-mining co-proprietor.

Because of the above, we believe that, compared with other available mechanisms including resorting to types of protection already known in the SNAP (national system of protected areas), the best potential for recognising territories of life in Ecuador is in the recognition and guarantee of Indigenous Peoples’ land rights. As explained in this section, in the framework of plurinationality, these rights provide a greater protective scheme, particularly regarding the possibility of self-government; however, it is potential, since, as also indicated, the developmentalist bias still takes precedence. The Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubio communities have the constitutional basis to claim an equivalent treatment to Indigenous rights, as applicable, but the other Mestizo and rural communities do not have an explicit protection framework like the Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian and Montubio communities. However, they do hold constitutional rights related to a healthy and ecologically balanced environment, to life, health, water, food, food sovereignty, prior environmental consultation and to claiming the rights of nature. They can argue these rights in their collective dimension and in the exercise of their autonomy, establish themselves as territories of life. In this case, recognition could be argued as the creative use of freedom of association (Art. 66.13) and collective organisation to “develop economic, political, environmental, social and cultural proposals and demands; and any other initiatives that contribute to good living.” (Art. 97 in the chapter on participation in democracy in the title on involvement and organisation of power). We are not aware of antecedents of this use of the law, but undoubtedly it could be pursued.

Defending territories of life

The peoples and communities affected by state extractivism without consent have taken up a historic fight to defend and conserve their territory, as much inside the borders of Ecuador as in the areas bordering Colombia and Peru. The Shuar nationality (Ecuador) and the Wampis Nation (Peru) acknowledge each other, state “we are the same blood”, and join efforts to strengthen collaborative action.[21] Based on shared life stories, including common threats, they defend their territory, a healthy environment free from contamination, and the integrity of nature.

This fight is based on each people’s and nationality’s own systems of governance, which are based on communities, assemblies, parliaments and governing boards. They are the spaces from which alliances are formed and relationships are built to progress with their life plans. They are the spaces in which decisions are made to protect and defend their territories against extractive activities driven by the state and carried out by private companies, where they are held accountable before the collective and where strategies and the way forward are rethought.

“We must fight, men and women, to defend our territories. We have to continue even more strongly to conserve our heritage, our forests, and care for nature, because this is our legacy for our daughters and sons, for our grandchildren and our contribution to caring for life all over the world”.

The strengthening of own forms of government and the defence of Indigenous peoples’ and nationalities’ territories coincide with the vision, objectives and actions promoted by the ICCA Consortium through the promotion of adequate recognition processes for territories of life, ICCAs, hence why some of the country’s Indigenous peoples and nationalities and local communities continue to join this initiative. The territories of Indigenous Peoples and local communities have driven self-strengthening, documentation and registration processes, with the support of the GEF/UNDP/SGP initiative and the member organisations of the ICCA Consortium in Ecuador.

The territories of life that are registered and in the process of registering in Ecuador possess significant biodiversity, culture and knowledge, and their own organisational structures enabled them to take measures to address COVID-19. Collective responses like the production of plants and traditional medicine, or collective food cultivation allowed them to respond to the crisis caused by the health emergency and containment measures.

Meanwhile, they had to deal with the onslaught of balsa wood exploitation in their forests, which experienced an unusual rush due to economic stimuli in countries like China and Germany regarding renewable energy. Balsa wood is required as a raw material for the production of wind turbine blades.[22] In the middle of the lockdown, the worst oil spill in recent years took place, affecting approximately 25 thousand Kichwa families in the north of the Ecuadorian Amazon, with no adequate response from the state to date.

Since the start of the pandemic, the state has not managed to act diligently or responsibly to provide a culturally differentiated treatment for the country’s Indigenous peoples and nationalities, who had to make their own arrangements to address their needs. The only available information about the impact of COVID-19 on Indigenous peoples and nationalities arose from efforts driven by CONFENIAE[23] which record that, up until December 2020, 3257 people were affected by COVID-19.

Lessons learnt and challenges in the process of recognising territories of life in Ecuador

In Ecuador, several lessons can be drawn from the promotion of the recognition of territories of life, the processes of self-strengthening, mutual support, peer recognition and registration in the global ICCA Registry since 2017.[24] Territories of life contribute to:

1) the exercise of collective rights, within the framework of territorial self-determination, and they are a contribution to the construction of the plurinational state; 2) the strengthening of their own governments, based on the participation of women, men and young people, and on the application of mechanisms such as community consultation, permanent dialogue and the popularisation of actions taken; 3) the strengthening of their identity, which manifests itself in the recovery and revaluation of their identity as an Indigenous people or nationality, or as a local community; 4) the defence and conservation of their territories, with territory being understood in an integral way, as a system in equilibrium, in intimate relationship with nature; 5) the mitigation of impacts of the climate crisis, which means that territories of life are becoming a benchmark for proposals for the conservation of territories; 6) women’s protagonism in the process of defending and sustaining territories of life; and 7) peer-to-peer recognition to share knowledge, know-how and experiences for the construction of knowledge and the promotion of collective strategies.

The following are some of the proposals identified for the process of territories of life in the future:

- Build a public policy proposal on the basis of the processes driven by Indigenous peoples and local communities, to be presented to the legislative and executive levels, in order to sustain, expand and support the exercise of their rights, the protection of their territories and the conservation of nature in the framework of a plurinational and intercultural state.

- Strengthen territorial defence strategies through the recognition of self-government, Indigenous justice and legal security over territories.

- Continue with the ICCA process and promote alliances to strengthen the territorial defence actions of Indigenous peoples and local communities. These alliances could include cross-border, bi-national, Amazonian and Latin American processes.

- Generate spaces of articulation with different actors that support the appropriate recognition and strengthening of ICCAs-territories of life: local governments, academia, NGOs, international cooperation.

- Support current and new processes carried out by Indigenous peoples and local communities through training programmes, exchange of knowledge and experiences.

Conclusion

Ecuador, a plurinational and intercultural state, recognises the collective territorial rights of Indigenous peoples and nationalities, the Afro-Ecuadorian people and the Montubio peoples. Territorial rights guarantee imprescriptibility, inalienability and indivisibility and their own systems of governance; they also consider their ancestral ownership and consolidate a physical and spiritual space necessary to maintain their identity, traditions and social organisation, to generate and exercise their authority, and to maintain, develop and apply their rights. Collective rights include participation, through free, prior and informed consultation, in state decisions on non-renewable resources existing in their territories.

In this context, state policy, through the national government, promotes a developmentalist model based on extractive industries: oil and mining, hydroelectric dams, logging and intensive agriculture that directly affect the peoples, their territoriality and their collective rights. These state actions have historically meant the reduction of their territories, the displacement of peoples and the destruction of their vital spaces.

Faced with this reality, the peoples and local communities maintain their historical and permanent struggle for the full exercise of their rights, their self-determination, their territorial rights, their systems of governance and their ways of life. For this, they are pursuing alternatives for the construction of their own proposals of self-government and conservation, such as the Achuar System of Conservation and Ecological Reserves, Kawsak Sacha-Living Forest of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku (see this report), Kayambi People, among others. Further, they are taking legal action at the national level (a’i kofán of Sinangoe, Waorani communities of Pastaza, Río Piatua and Río Blanco) and at the international level (e.g., the ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in favour of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku), advocacy to amend Ecuadorian legislation, as well as conservation and integral protection systems and programmes (SNAP, Bosque Protectores, Socio Bosque, among others).

The objectives and actions promoted by the ICCA Consortium are aligned with the processes of self-government and territorial defence of the peoples and nationalities. The recognition as territories of life, or ICCAs, contributes significantly to their struggle. Through their registration as territories of life, the communes of Playa de Oro and Agua Blanca in the coastal region, the Shuar Arutam People, the Waorani Nationality and the Waorani Women’s Association, the Kichwa People of Sarayaku and the Achuar Nationality of Ecuador, as well as other nationalities and peoples, gained access to an international mechanism that contributes to the defence of their territories, making them part of a global network to sustain and defend biodiversity and life, as well as their defenders.

[1] Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda, INEC, 2010. According to the census methodology, self-identification according to culture considers the following options: Indigenous, Afro-Ecuadorian, Montubio/a, Mestizo/a, White, Other.

[2] The Tagaeri Taromenane are isolated family groups, linguistically and culturally related to the recently-contacted Waorani nationality. Narváez, et al. 2020. Pueblos indígenas aislados y de reciente contacto (Waorani) en la Región del Yasuní: estado, vulneración de derechos y amenaza a la vida en el contexto de la pandemia de COVID-19, Quito, Ecuador: Fundación ALDEA, Fundación Pachamama.

It is likely that there are other peoples in isolation in the Ecuadorian Amazon, a subject on which further research is urgently needed.

[3] Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Amazonía Ecuatoriana

[4] Confederación de Pueblos de la Nacionalidad Kichwa del Ecuador

[5] Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas de la Costa Ecuatoriana

[6] Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador

[7] Confederación Nacional de Organizaciones Campesinas, Indígenas y Negras

[8] Consejo de Pueblos y Organizaciones Indígenas Evangélicas del Ecuador

[9] Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica

[10] Coordinadora Andina de Organizaciones Indígenas

[11] According to information from the MAAE, by 2020 it was 20.35% of the land area (including the Galapagos National Park) and 12.07% of the marine area (including the Galapagos Marine Reserve). “Estadísticas del Sistema Nacional de Áreas Protegidas SNAP – 2020.”

[12] http://areasprotegidas.ambiente.gob.ec/es/info-snap

[13] http://areasprotegidas.ambiente.gob.ec/info-snap

[14] https://www.wwf.org.ec/noticiasec/?uNewsID=365496

[15] http://sociobosque.ambiente.gob.ec/node/44

[16] https://www.landrightsnow.org/the-shuar-arutam-people-defend-their-territories-and-biodiversity/

[17] http://www.pueblosynacionalidades.gob.ec/la-asamblea-nacional-concedio-amnistia-a-las-20-autoridades-indigenas-de-la-comunidad-de-san-pedro-del-canar/

[18] https://www.dpe.gob.ec/fallo-historico-a-favor-de-la-nacionalidad-ai-cofan-de-sinangoe-contra-la-mineria/

[19] https://www.amazonfrontlines.org/chronicles/victoria-waorani/

[20] https://www.derechosdelanaturaleza.org.ec/rio-piatua/

[21] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEOC6PgaX-I

[22] https://www.opendemocracy.net/es/fiebre-madera-balsa-pandemia-territorio-achuar/ y https://www.infobae.com/america/agencias/2020/07/18/la-balsa-de-la-esperanza-y-de-la-deforestacion-en-ecuador/

[23] https://confeniae.net/covid19

[24] ALDEA 2020. Memorias: Reunión del Consorcio TICCA – Ecuador. Quito: Fundación ALDEA