A Critical-Biographical Profile

Albert Renger-Patzsch

THE WORLD IS BEAUTIFUL

Spring 1993 Donald KuspitALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH

A CRITICAL-BIOGRAPHICAL PROFILE

DONALD KUSPIT

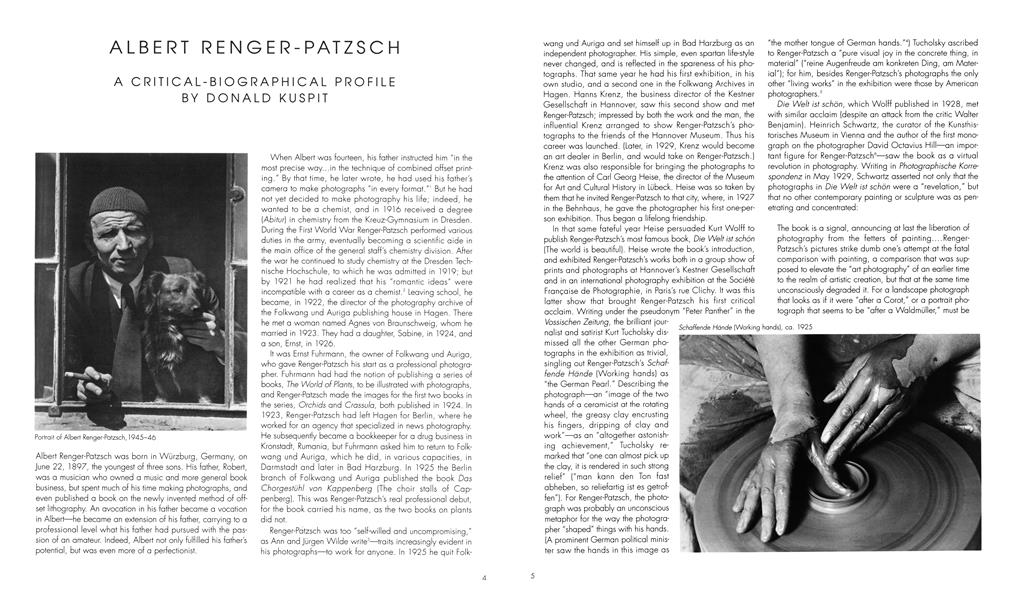

Albert Renger-Patzsch was born in Würzburg, Germany, on June 22, 1897, the youngest of three sons. His father, Robert, was a musician who owned a music and more general book business, but spent much of his time making photographs, and even published a book on the newly invented method of offset lithography. An avocation in his father became a vocation in Albert—he became an extension of his father, carrying to a professional level what his father had pursued with the passion of an amateur. Indeed, Albert not only fulfilled his father's potential, but was even more of a perfectionist.

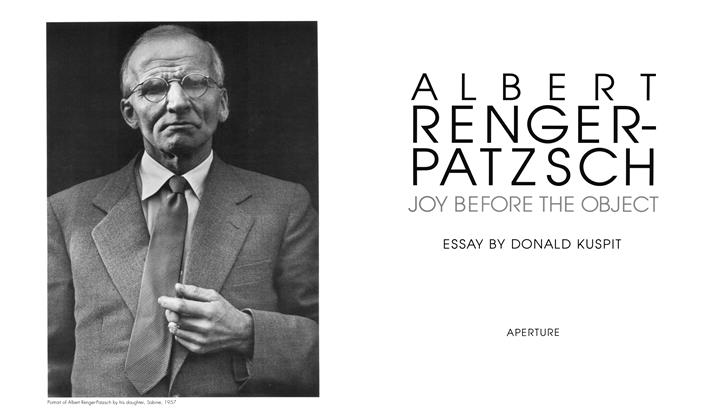

When Albert was fourteen, his father instructed him "in the most precise way...in the technique of combined offset printing." By that time, he later wrote, he had used his father's camera to make photographs "in every format."1 But he had not yet decided to make photography his life; indeed, he wanted to be a chemist, and in 1916 received a degree {Abitur) in chemistry from the Kreuz-Gymnasium in Dresden. During the First World War Renger-Patzsch performed various duties in the army, eventually becoming a scientific aide in the main office of the general staff's chemistry division. After the war he continued to study chemistry at the Dresden Technische Hochschule, to which he was admitted in 1919; but by 1921 he had realized that his "romantic ideas" were incompatible with a career as a chemist.2 Leaving school, he became, in 1922, the director of the photography archive of the Folkwang und Auriga publishing house in Hagen. There he met a woman named Agnes von Braunschweig, whom he married in 1923. They had a daughter, Sabine, in 1924, and a son, Ernst, in 1926.

It was Ernst Fuhrmann, the owner of Folkwang und Auriga, who gave Renger-Patzsch his start as a professional photographer. Fuhrmann had had the notion of publishing a series of books, The World of Plants, to be illustrated with photographs, and Renger-Patzsch made the images for the first two books in the series, Orchids and Crassula, both published in 1924. In 1923, Renger-Patzsch had left Hagen for Berlin, where he worked for an agency that specialized in news photography. He subsequently became a bookkeeper for a drug business in Kronstadt, Rumania, but Fuhrmann asked him to return to Folkwang und Auriga, which he did, in various capacities, in Darmstadt and later in Bad Harzburg. In 1925 the Berlin branch of Folkwang und Auriga published the book Das Chorgestühl von Kappenberg (The choir stalls of Cappenberg). This was Renger-Patzsch 's real professional debut, for the book carried his name, as the two books on plants did not.

Renger-Patzsch was too "self-willed and uncompromising," as Ann and Jürgen Wilde write3—traits increasingly evident in his photographs—to work for anyone. In 1925 he quit Folkwang und Auriga and set himself up in Bad Harzburg as an independent photographer. His simple, even spartan life-style never changed, and is reflected in the spareness of his photographs. That same year he had his first exhibition, in his own studio, and a second one in the Folkwang Archives in Hagen. Hanns Krenz, the business director of the Kestner Gesellschaft in Hannover, saw this second show and met Renger-Patzsch; impressed by both the work and the man, the influential Krenz arranged to show Renger-Patzsch's photographs to the friends of the Hannover Museum. Thus his career was launched. (Later, in 1929, Krenz would become an art dealer in Berlin, and would take on Renger-Patzsch.) Krenz was also responsible for bringing the photographs to the attention of Carl Georg Heise, the director of the Museum for Art and Cultural History in Lübeck. Heise was so taken by them that he invited Renger-Patzsch to that city, where, in 1927 in the Behnhaus, he gave the photographer his first one-person exhibition. Thus began a lifelong friendship.

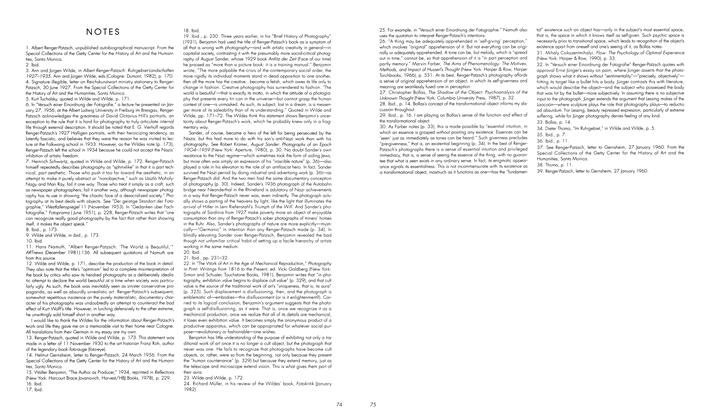

In that same fateful year Heise persuaded Kurt Wolff to publish Renger-Patzsch's most famous book, Die Welt ist schön (The world is beautiful). Heise wrote the book's introduction, and exhibited Renger-Patzsch's works both in a group show of prints and photographs at Hannover's Kestner Gesellschaft and in an international photography exhibition at the Société Française de Photographie, in Paris's rue Clichy. It was this latter show that brought Renger-Patzsch his first critical acclaim. Writing under the pseudonym "Peter Panther" in the Vossischen Zeitung, the brilliant journalist and satirist Kurt Tucholsky dismissed all the other German photographs in the exhibition as trivial, singling out Renger-Patzsch's Schaffende Hände (Working hands) as "the German Pearl." Describing the photograph—an "image of the two hands of a ceramicist at the rotating wheel, the greasy clay encrusting his fingers, dripping of clay and work"—as an "altogether astonishing achievement," Tucholsky remarked that "one can almost pick up the clay, it is rendered in such strong relief" ("man kann den Ton fast abheben, so reliefartig ist es getroffen"). For Renger-Patzsch, the photograph was probably an unconscious metaphor for the way the photographer "shaped" things with his hands. (A prominent German political minister saw the hands in this image as "the mother tongue of German hands."4) Tucholsky ascribed to Renger-Patzsch a "pure visual joy in the concrete thing, in material" ("reine Augenfreude am konkreten Ding, am Material"); for him, besides Renger-Patzsch's photographs the only other "living works" in the exhibition were those by American photographers.5

Die Welt ist schön, which Wolff published in 1928, met with similar acclaim (despite an attack from the critic Walter Benjamin). Heinrich Schwartz, the curator of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the author of the first monograph on the photographer David Octavius Hill—an important figure for Renger-Patzsch6—saw the book as a virtual revolution in photography. Writing in Photographische Korrespondenz in May 1929, Schwartz asserted not only that the photographs in Die Welt ist schön were a "revelation," but that no other contemporary painting or sculpture was as penetrating and concentrated:

The book is a signal, announcing at last the liberation of photography from the fetters of painting....RengerPatzsch's pictures strike dumb one's attempt at the fatal comparison with painting, a comparison that was supposed to elevate the "art photography" of an earlier time to the realm of artistic creation, but that at the same time unconsciously degraded it. For a landscape photograph that looks as if it were "after a Corot," or a portrait photograph that seems to be "after a Waldmüller," must be a hybrid, occupying an unclear position between painting and photography without justifiably being able to claim recognition as an independent artistic creation. Renger-Patzsch's pictures are too personal in form, unique in theme [Ausschnitte], and "unpainterly" in motive for a superficial comparison with painting to be able to explain or clarify them. Who thinks of [Lovis] Corinth in front of Renger-Patzsch's photographs of flowers, who thinks of an animal painter in front of his delineation [Lineament] of an adder's head, who can find any parallel in painting to his shoe lasts, clothing material, insulator chain, guide rail, or the links of the coupling? It would be an idle undertaking. In this lies the meaning of photography: it does not want to simulate [vortauschen] and it does not want to veil. It does not want to be anything more or less than photography. And finally it wants to prove its independence and freedom from painting.7

For Schwartz, Renger-Patzsch's photographs not only accomplish this, by reason of his strong "experience of the things of the visible environment," but they communicate that experience to the spectator through an "intensity" that can be felt through the "medium of the 'dead apparatus.'"8

At the end of the twenties the city of Essen encouraged artists to settle there. Renger-Patzsch accepted, moving with his family to a home on the Margarethenhöhe in 1928. Establishing a studio and laboratory in the Folkwang Archives, he received commissions from industry, architects, and publishers. In the Ruhr region he found a unique "'landscape,' a mix of bourgeois homes, worker settlements, backyards, mines, metal foundries, dumps, streets, garden colonies, and agriculture in narrow plots, and began to photograph it."9 FHe also developed an interest in literature, and began a correspondence with Hermann Hesse. Relationships like this one resulted in a number of portrait photographs, which he almost never exhibited. Though he admired, for example, Hugo Erfurth, in general he thought successful portrait photographers rare.

Renger-Patzsch quickly became part of the artist and craftsman community in the Ruhr, establishing friendships with the goldsmith Elisabeth Treskow, the craftsman and printer Herman Kötelhön, the painter and draftsman Hermann Schardt, and Johannes Molzahn, a founder of the Breslau Academy. In 1933, Max Burchartz, the director of the Folkwangschule, invited him to teach photography there; Renger-Patzsch was pleased, not only because of the recognition that the appointment implied, of photography as well as of himself, but because it would afford him economic security. He taught only two semesters there, however, in 1934. The Nazis had begun to take over the art schools, and to dismiss anyone who didn't accept their conception of art. Renger-Patzsch would not compromise his ideas and sacrifice his academic freedom, and he resigned.

As before, he continued to earn his living from industry, architects, and publishers. He accepted commissions from the Schott glassworks in Jena, the Schloemann apparatus manufacturers, Krupp, and the Fagus works. He was also employed by the architects Fritz Schupp, Alfred Fischer, Rudolf Schwarz, and Otto Haesler, and by the publishers Langewiesche in Wasserburgen, Ferdinand Schöningh in Paderborn,and the Deutscher Kunstverlag in Oberrhein. This work excused him from service in the Second World War. Many of the artists and writers he knew were forbidden to work, or emigrated; some were even imprisoned in concentration camps. All of this seems to have shocked and depressed him.10

In 1944 the major part of Renger-Patzsch's archives in the Museum Folkwang was destroyed by Allied bombing. He and his family moved in with the Kätelhöns, who had left Essen for Wamel many years earlier. After the war, RengerPatzsch decided to stay in Wamel—he felt comfortable in the Möhnesee landscape. For the remaining years of his life, nature was his major theme. This was the period when RengerPatzsch established contact with such writers as Heinrich Boll and Ernst Jünger. Dr. Ernst Boehringer financed both his books and his travels through Europe in search of fresh landscapes; Renger-Patzsch was known to travel sixty to eighty kilometers to photograph a particular tree in early-morning light. Before photographing stones, he would read books on geology and geography. Jünger, impressed by his pictures, wrote the introduction for his last two books, Bäume (Trees) and Gestein (Stones). Shortly after the appearance of Gestein, and after a long illness, the photographer died, in Wamel, on September 27, I960.

THE WORLD IS BEAUTIFUL

For Hans Namuth, an American photographer of German descent a generation younger than Renger-Patzsch, the hundred photographs in Die Welt ist schön brought to mind "the poetry of Renger-Patzsch's two great contemporaries Rainer Maria Rilke and Bertolt Brecht."’1 Noting that Brecht's "masterpiece, hlauspostille, a collection of over fifty poems, was published in 1927," just a year before Renger-Patzsch's masterpiece, Namuth writes, "One of Brecht's verses is addressed to a tree. In it, the author praises and congratulates Green, the lonely tree, for having survived a night of violent storms. Two lines read, 'You live quite alone, Green?/Yes, we are not for the masses.'" For Namuth, Renger-Patzsch's photographs are comparable to poems like this one in quality, theme, and attitude. And the photographer is as great as the poet.

The critical issue of Renger-Patzsch's photography is the camera's "consciousness" of things—that is, the use of the camera to intensify our consciousness of them. Namuth knew that Renger-Patzsch had wanted his book to be called Die Dinge (Things), but that the publisher, Kurt Wolff, thought the title Die Welt ist schön would be more commercial.12 RengerPatzsch was depressed by Wolff's decision; he felt that the new title would lead to misunderstanding of his photographs, compromising and tainting them. This was why he ironically dismissed the book as a "visiting card": the title had reduced it to banal "proof that he was able to photograph."13

What's in a name? It is a familiar, seemingly unanswerable question. At issue is the power of the word over the image— the word's power to focus the image in the eyes of the world, so that it is seen in a particular way. The responses of a number of contemporary viewers of Die Welt ist schön suggest that Wolff's title did no harm. Thomas Mann reviewed the book positively for the Berliner lllustrirte, praising RengerPatzsch's "originality" and the "boldness of his choice of objects and point of view"; for Mann, Renger-Patzsch was one of the two most important photographers in the world. (The other was Emil Otto Hoppé, in London.) And Helmut Gernsheim, a prominent connoisseur and critic of photography, later wrote that he thought that the book was a "turning point" in the history of photography, along with László Moholy-Nagy's "pioneering work" in the Bauhaus.14

On the other hand, the title Die Welt ist schön certainly predisposed Walter Benjamin to see Renger-Patzsch's book as an example of the "New Matter-of-Factness" whose "stock in trade was reportage,"15 and Renger-Patzsch himself as a photographer on the model of "the hack writer" who "possessed no other social function than to wring from the political situation a continuous stream of novel effects for the entertainment of the public."16 This myopic reaction would seem to justify Renger-Patzsch's fears. The photographer's real fault in Benjamin's eyes, however, was more fundamental: neither his technique nor his content was revolutionary.

At issue was a basic debate over the function of art, an issue that remains unresolved to the present day. For Benjamin, Renger-Patzsch's version of reality ignored, or suppressed, its political aspect, exhibiting a neutrality that betrayed the leftwing social cause, however unintentionally. To the Marxist Benjamin there was no such thing as political neutrality—if one was not actively in favor of the revolution, one was passively against it. Thus Renger-Patzsch was automatically a reactionary. This was apparently confirmed by the way his photographs seemed to beautify socially produced things, or else articulated the supposedly inherent beauty of natural things; to Benjamin, this meant that he didn't just have a naive view of reality, he consciously falsified it. His photography conformed to an old aesthetic of transfiguring appearances, rather than to the new artistic ideal of using art to influence social opinion, and even as direct social action. To keep the medium of photography in this retarded state of ideological innocence and indifference was to betray its promise, indeed, for Benjamin, its destiny: its use value as a means of disclosing class character and the reality of social power.

(continued on page 66)

Namuth describes how Renger-Patzsch emphasizes the details of things until they seem to "vibrate with life, some to a disturbing degree." It is a quality that strikingly distinguishes these photographs from what Benjamin called "reportage." But so blind is Benjamin to this quality, so savagely did he attack the work, that one wonders whether he actually looked at it more than passingly. He preferred an artist such as John Heartfield, who made photomontage a dialectical, antiaesthetic "political instrument" with "the revolutionary strength of Dadaism," "testing art for its authenticity," like Dada, by showing that "the tiniest fragment of daily life says more than painting."17 In painting, Benjamin argued, the "picture frame ruptures time"18 to create a feeling of mythical unity and integrity, repressing the picture's social meaning. And Renger-Patzsch's photography similarly eternalized and aestheticized the miserable social environment. Where Heartfield made social contradictions ironically transparent, Renger-Patzsch made them seem falsely inevitable:

There is an urgent need to examine old opinions and look at things from a new viewpoint. There must be an increase in the joy one takes in an object, and the photographer should become fully conscious of the splendid fidelity of reproduction made possible by his technique. Nature, after all, is not so poor that she requires constant improvement.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch "Joy Before the Object," 1928

The fact that a fragment can symbolize the whole, and that enjoyment and empathy are mutually exalting when the imagination is forced to collaborate in the experience—this is an area in which landscape photography offers a multitude of possiblities.

—Carl Georg Heise, from The World is Beautiful, 1929

The absolutely correct rendering of form, the subtlety of tonal gradation from the brightest highlight to the darkest shadow, impart to a technically expert photograph the magic of experience. Let us therefore leave art to the artists, and let us try to use the medium of photography to create photographs that can endure because of their photographic qualities....

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1927

I lean toward Stephen's view that the [Otto] Steinert school of photography is headed toward a dead end. Man Ray and Moholy, and to an extent Florence Henri, did it all much better back in 1925. While people like Cartier-Bresson and Bill Brandt, in my opinion, represent a new era in photography. Using the extraodinary new techniques available today, they are setting a course that was suggested in the work of Atget, occasionally also in Stieglitz, but which far surpasses both of them. Sometimes I have the feeling that this type of picture-taking is the first legitimate assignment for photographers, that is, an assignment that could only be carried out by photography.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1956

If he is a great master of the technique, then in a moment [the photographer] can conjure up things which will call for days of effort from the artist, or may even be totally inaccessible to him, in realms which are the natural home of photography. Whether it be as the sovereign mistress of the fleeting moment, or in the analysis of individual phases of rapid movement; whether to create a permanent record of the transient beauty of flowers, or to reproduce the dynamism of modern technology.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1929

I'd like to briefly state the accomplishment that we expect from a photographer. He must make the person being photographed forget that he has eaten from the tree of knowledge.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1956

We still don't sufficiently appreciate the opportunity to capture the magic of material things. The structure of wood, stone, and metal can be shown with a perfection beyond the means of painting.... To do justice to modern technology's rigid linear structure, to the lofty gridwork of cranes and bridges, to the dynamism of machines operating at one thousand horsepower—only photography is capable of that.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, 1927

For many years a certain higher ambition defined my existence, which had in general only to do with my profession. This later changed fundamentally. I now can only view my profession as part of the larger story of my life. To be fair, though, I must admit that this ambition gave rise to worthy achievements...which in turn had an effect on my overall outlook. I will briefly outline the consequences: an insurmountable aversion to any ideology, which in my experience always degenerates into political or intellectual dictatorship, and a predilection for Knowledge as the force of order and reason that teaches us the relative importance of Things.

—Albert Renger-Patzsch, ca. I960

(continued from page 7)

In Renger-Patzsch, photography could no longer depict a tenement block or a refuse heap without transfiguring it. It goes without saying that photography is unable to say anything about a power station or a cable factory other than this: what a beautiful world! A Beautiful World—that is the title of the well-known picture anthology by Renger-Patzsch, in which we see New Matter-ofFact photography at its peak. For it has succeeded in transforming even abject poverty, by recording it in a fashionably perfected manner, into an object of enjoyment. For if it is an economic function of photography to restore to mass consumption, by fashionable adaptation, subjects that had earlier withdrawn themselves from it— springtime, famous people, foreign countries—it is one of its political functions to renew from within—that is, fashionably—the world as it is.19

For Benjamin, Renger-Patzsch's photography is "a flagrant example of what it means to supply a productive apparatus without changing it. To change it would have meant to overthrow another of the barriers, to transcend another of the antitheses, that fetter the production of intellectuals, in this case the barrier between writing and image. What we require of the photographer is the ability to give his picture the caption that wrenches it from modish commerce and gives it a revolutionary useful value."20 Not only did Renger-Patzsch's photographic "new matter-of-factness," like literature's "new matter-of-factness," make "the struggle against poverty an object of consumption,"21 its emphasis on the sheer givenness of things denied their social text. The photographs didn't seem to interpret things in the act of mediating them, didn't function critically to expose ordinary appearances as an ideological facade and social symptom. For Benjamin, this constituted a social naiveté, which extended into Renger-Patzsch's attitude to the camera. Benjamin implicitly saw photographs as mechanical constructions, reproducing in their smallest details the camera's own mechanicalness; this is why he thought photographs were inevitably, or properly, a means of disillusionment, rather than a new means of illusion.22 Renger-Patzsch, on the other hand, seemed to regard the camera "mystically," that is, as an instrument of revelation, a way of piously worshiping things.

Political tunnel vision made it impossible for Benjamin to contextualize Renger-Patzsch's photographs in a way that would do them justice. Like commissars of every ideological stripe, he consigned to intellectual oblivion whatever did not seem revolutionary fit. Perhaps a more considered, less prejudiced look at this work might have put Benjamin's own revolutionary fervor in question. Perhaps he did not want that closer look, for it might have led him to question whether the social or class identity of a thing supersedes every other identity it has. He might have realized that his "Marxification" of things forced them into as narrow and dogmatic a procrustean bed as he thought Renger-Patzsch's sort of contemplation did, without necessarily affording more insight into their reality (as though there was only one salient reality, one relevant kind of insight).

Benjamin failed Renger-Patzsch's photographs, in a failure of seriousness as well as of attention, of imagination as well as of intellect. It was an astonishing lapse for a thinker of Benjamin's astuteness and powers of observation. Taking the shadow of a book, its readymade title, for its substance, he betrayed his attitude toward anything he could not press-gang into the social cause. Loading the dice against Renger-Patzsch by the comparison with Heartfield, he revealed the limits of his own understanding of photography's formal possibilities. Perhaps Benjamin didn't expect photography to have formal possibilities. Perhaps, because Renger-Patzsch gave things a certain aura—could photography really do that?—Benjamin found him regressive. As the Wildes note, Benjamin may have attacked Renger-Patzsch's photographs because of their commercial success,23 which linked them with fashion and entertainment—as though these distractions were the primary reasons that social revolution had not occurred. If so, Benjamin conveniently forgot that Heartfield's photomontages, which he admired for their revolutionary content, were also successful, no doubt in part because they were fashionably and entertainingly avant-garde. Indeed, their aesthetic liveliness converged with their radical chic to make them "high" fashion and entertainment.

Renger-Patzsch was obsessed with things as such; Benjamin was obsessed with revolution. It is as though Benjamin forgot that photography had something to do with perception. Does Namuth appreciate Renger-Patzsch's photographs as he does simply because he is also a photographer, unexpectedly discovering his connection with a predecessor? Benjamin was a social critic and intellectual, sensitive to photography but wanting it to serve a revolutionary and theoretical cause; Namuth is a practicing photographer, as absorbed with art and creativity as Benjamin was with revolution, and convinced that before photography is anything else it is a creative process, a creative response to reality, and that a photographer can make as important work as any artist. Indeed, RengerPatzsch's photography demonstrated the truth of this. Is the idea that photography is a young medium, whose practitioners are still discovering creative possibilities unique to it, reconcilable with the belief that it is simply one more means of social production that must become an instrument of revolutionary politics, that must be enlisted on the right social side lest it fall into the wrong hands?

Namuth notes that he saw his first Renger-Patzsch photograph, Kauper; von unten gesehen (Smokestack, as seen from below), 1928 (page 35), in a "shop window in an ordinary neighborhood" in Essen. That city, Namuth's hometown, is also the place where Renger-Patzsch "spent much of his early life" and lived from 1928 to 1944, "when he lost his home and nearly all his archives in an air raid." For Namuth, Kauper, von unten gesehen was "a sobering picture, very black and white, with multiple grays all over." The "giant smokestack" rose into the sky "with phallic grandeur." What would Benjamin think of Namuth's sexual association, which shuns sociopolitical meaning? What would he have thought of Namuth's realization, on seeing the image again, years later, "that it had been with me all my life"? Or of Namuth's assertion that a "railing, balcony-like," had been photographed "in such a way that it had "a light and lacy appearance," making the image a creative triumph, for it "was clearly a new way of celebrating the ugly and the banal"?

For Benjamin, the point is not to celebrate, with whatever aesthetic subtlety, the ugly and the banal, but to expose why there is so much ugliness and banality in the world. No doubt he would have regarded Namuth's phallic metaphor as an arbitrary, subjective (if somewhat predictable) association, and, as such, as a distraction from the smokestack's objective social meaning. Another critic might say that Namuth was empathically identifying with a fellow Essener as a way of finding some reason for being in a city that was no longer home—that but for the grace of God, Namuth, like RengerPatzsch, might have remained in Essen during the war, and might have lost his archives; and that Namuth's phallic projection, a delusion of masculine grandeur, might be a compensation for a feeling of impotence and vulnerability. For Benjamin, this, too, would be irrelevant, subjective speculation.

Is it Namuth who tells us the truth about Renger-Patzsch, or is it Benjamin, or does each only know part of the truth? Or is the truth polyvalent: are both correct? Both men implicitly acknowledge Renger-Patzsch's photographs as uncannily— not just conventionally—true. These images seem to carry photography's vaunted "truth-to-things" to a new level, affording a perceptual epiphany. There is a sense of conviction in RengerPatzsch's photographs that we do not have in ordinary perception. In fact, for both Benjamin and Namuth, RengerPatzsch's work is a "peak" of photography—it is Benjamin's word—for the same reason: its remarkable power of transfiguration. For Benjamin, though, this creative power signals complicity in the social status quo, while for Namuth it privileges the works as art. "Renger-Patzsch did not want to be called an artist," Namuth writes; "he felt that photography was not an art, nor a craft, but a category by itself." Yet "his utter simplicity of form and of light versus shadow was perhaps equaled but never surpassed by Edward Weston." (He has been called "the German Weston.") And he achieved a "lyrical Neue Sachlichkeit," a "'new objectivity'... of a different order altogether" from what "the Bauhaus had been teaching for a number of years."

THE HIDDEN ORDER OF DETAILS

Renger-Patzsch's critics invariably categorize his images as part of the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). (The exception is Richard Müller, who perceptively sees in their "sensuous quality" a certain "visionary" attitude.24) The label misses the point: the best of these works are not matter-of-fact descriptions or naive mimetic representations of things, but rather involve an unconscious perceptual identification with them. Renger-Patzsch may have been subliminally aware of this phenomenon, as is suggested by his frequent quotation of Goethe's notion that "the hardest thing to see is what is in front of your eyes."25

It is hard to focus on what is in front of one's eyes because that thing is implicitly part of oneself, if only in passing. The sense of immediacy that derives from the focused gaze gives the thing a psychic significance it would otherwise lack, while at the same time making it hard to grasp the depth of that significance. Immanent in the thing is its inner meaning, which, paradoxically, is obscured by its physical immediacy. However, also paradoxically, an aesthetic intensification of such immediacy can disclose inner meaning.

It is an aesthetic feat to see what is in front of our eyes, and one that we rarely attempt. It seems beside the point of our everyday relationship to things to see them aesthetically, let alone ecstatically—it is easier and more practical to deal with them as matter-of-fact signs of themselves. Thus our perception of things can become so habitual that the things seem to be more sign than substance. Actually, seeing them otherwise can be emotionally dangerous.

To mistake a thing as a sign, however, is to be blind to the complexity of its being, and thus be unable to test the reality of that complexity through perception. This also means that one is unaware of the complexity of perception. RengerPatzsch's images fight this double simplification—of the thing's being, and of the kind of perception that ordinary consciousness carries out to reassure itself. In his best work he enlists the phenomenological pursuit of the self-given ness of the thing26 in the service of an "aesthetic moment...of 'rapt, intransitive attention,'"27 a moment involving "perceptual identification" with the thing to the extent of symbiotic merger with it.28 Both the aesthetic moment, a kind of epiphany of the thing, and the perceptual identification with the thing—an identification that occurs in the aesthetic moment, indeed, that the moment exists to facilitate—have the same refreshing point: the sense that the aestheticized object can in its turn aestheticize or transform the subject, inducing a feeling of being renewed or reborn.29 The object, then, becomes not just a metaphor for self-transformation and re-creation, but their catalyst.

However unwittingly, Renger-Patzsch made photography a method of phenomenological reduction involving an intuition of the thing in its essential givenness.30 His images suspend or bracket the existence of the thing in order to articulate its necessity, insisting on its identity as a constant, however manifold our experience of it. Thus Renger-Patzsch privileges photographic perception as a way of establishing the thing's constancy. But the photograph does more for him: it offers an empathie rapport, fusion, and finally complete identification with the thing. His photographs suggest his deep, extraordinary experience of objects by way of their details, which turn the object into an uncanny process, in turn suggesting the uncanniness of one's perceptual relationship with it. This undermines—indeed, overturns—the ordinary, naive reading of these images as matter-of-factly realistic. The phenomenological transformation of the thing is inseparable from the symbiotic transformation of the self, and has the same result: intuition of the self-sustaining process of immanence that the self is, whether as object or subject.

It is, then, to Renger-Patzsch's sense of detail that we must turn—to his intensification of the details that constitute appearances, his way of making the thing seem more profound and uncanny than it does in ordinary perception. If, as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi argues, attention can be understood as a kind of "psychic energy...under our control, to do with as we please," and if, circularly, "we create ourselves by how we invest this energy,"3' then Renger-Patzsch invests nearly all the energy of his photographic attention in the details of things, creating an almost autonomous "grain"—a subliminal text of cryptic details that is not entirely readable in terms of the overarching representation, and that encodes an unconscious attitude to the reality it represents. The photographer is the person who can perceive and make visible the hidden order of details, implicitly by acknowledging and mobilizing the hidden order in himor herself. The externals under control, one is no longer privately anxious. Hence the absence of pathos, social or personal, in Renger-Patzsch's photographs, which many critics have noticed.32Renger-Patzsch emphasizes the details of things almost to the point where they disrupt the representation. This is a kind of formalism, in that the details seem ecstatically independent of what they signify, and yet seem to signify something more essential than the representation of which they are a part. Renger-Patzsch does not exaggerate details into distortion; rather, he uses them to undermine any sense of the representation's uniformity. He ingeniously estranges them from the picture as a whole, creating a peculiar effect of disorientation, for all the familiarity of what is pictured. His sense of detail unfreezes the scene, only to leave us caught between the awareness of the object depicted and an intense association with its component parts.

Whether in panoramas like Gartenkolonie in Bochum (Garden colony in Bochum), 1929, or in more intimate scenes such as Winkelstrasse in Essen (Street corner in Essen), 1939—two among many equally remarkable examples of his Ruhr photographs—Renger-Patzsch shows not simply his power of observation but his ability to give each detail equal weight without denying its integration with the rest of the photograph. So insistent are the details in these works that they form a kind of aesthetic texture apart from the representation—an "inner" composition that is the representation's real point, convincing us of its reality. In Gartenkolonie in Bochum the center of gravity is the foreground clothesline, with its sheets and towels, in Winkelstrasse in Essen it is the asymmetrically paired street lamp and hydrant, also in the foreground. From these points of departure the details of buildings and terrain spread and accumulate until they threaten to destroy the simple intelligibility of the view as such.

The roof ridges, the garden houses, the factory smokestacks, the church steeple ironically framed by the gas storage tank and barely topping the smokestacks (or is it struggling to reach their height?), all form independent if eccentric strata in Gartenkolonie in Bochum, as do the planes of bright snow that edge the roofs, the black metal bars of the fence, the grimy bricks in the wall, and the snow on the ground in Winkelstrasse in Essen. So much do these strata have their own formal integrity that they almost destabilize the representation, so that it is only barely seen as completely coherent. Renger-Patzsch's radical attention to the matrix of details—that is, his articulation of them as the roots of the scene—sets it in motion, until it seems simultaneously an expressive process and an invented construction.

This simultaneity is especially evident in Renger-Patzsch's photographs of trees—one of his tree photographs must have suggested Brecht's poem to Namuth—and in those of plants and animals, as in his famous Natterkopf (Snake's head), 1927 (page 59). In both its remarkable concreteness and its abstractness, this image is especially telling of the tension between detail and whole that pervades his work. Centered in the image, the snake's head is surrounded by its body. Both are rendered in startling, intimate, relentless detail, undermining any sense of the picture as standard illustration. Indeed, the identity of what we are looking at becomes unclear. If an eye did not mark one side of this flattened ellipse, we would lose the single reference that makes it clear we are looking at a living creature.

The experience of the image as almost an allover abstraction is confirmed by the flattening of the snake's body against the picture plane, making it all the harder to see what we are looking at as a simple matter of fact. Paradoxically, RengerPatzsch's intense scrutiny of the snake's body renders it inscrutable. Seen up close, rather than at a distance, that body becomes emotionally invasive as well as physically threatening. Renger-Patzsch shows us the evocative power a photograph can acquire simply by violating ordinary proxemics. But the basic point of his close-up seems to be to confront us with a creature utterly alien to us, and at the same time to show its uniqueness. We would find it impossible to imagine the reality of this creature if we weren't brought faceto-face with its unique existence. Renger-Patzsch's strategy of "concrete abstraction," in which details are given a definiteness that shatters ordinary, distanced perception, admirably succeeds. Natterkopf is an exemplary case of his generally celebratory approach to nature.

It must be emphasized that the snake's abstractness makes its otherness and difference not only externally real but inwardly real, so that it seems to bespeak the otherness and difference within us. Our eyes consciously moving along the labyrinthine coils that constitute its objective appearance, we unconsciously identify with it. This identification is triggered and reinforced by those coils' hypnotically repetitive scales, which give the snake a peculiar subjective aura. Lured by the strange reality and unreality, concreteness and abstractness, of the snake's body, we immerse ourselves in its mystery. It is as though, in putting this skin before our eyes in all its elementary and elemental detail, Renger-Patzsch were holding up a mirror to our inner selves.

Unexpectedly, Renger-Patzsch's impersonal, meticulously detailed photograph becomes a kind of personal delusion—a hallucinatory projection of an alien, primal part of ourselves, finally recognized and exposed. To the extent that the snake seems "destined" by Renger-Patzsch's "demonstration" of the abstractness of its existence, it bespeaks an aspect of our own destiny.

Wittingly or unwittingly, Renger-Patzsch is determined to "make it new," in Ezra Pound's words, or to afford "the surprise of the new," in those of Baudelaire. He is a modernist artist. The snake becomes new—is reborn in and through perception—in his austere articulation of its details. Pushing this articulation to the point where those details almost become unfathomable, Renger-Patzsch threatens to collapse the intelligibility of the representation. In Christopher Bollas's words, he moves toward "existential as opposed to representational knowing."33 The object acquires a transcendental necessity, and photographic perception becomes a radical act of knowing, in which the reality of the object, at the same time that it is directly acknowledged, is obliquely brought into question. Showing us the inherent abstractness of the snake's visual appearance (this is not the same thing as rendering it abstractly), Renger-Patzsch makes its existence speculative, as it were—and at the same time all the more certain, through its presentation as a kind of ideal datum of consciousness. To see these photographs as naively empirical or matter-of-fact is grossly to misread and simplify them.

THE RUHRGEBIET: AN INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE

When Renger-Patzsch began to photograph the Ruhr, the area had not yet been discovered as a theme, as Dieter Thoma notes.34 But Renger-Patzsch's sensitivity led him to recognize a novel world of stark contrasts, sensuous and social. This is a space of black and white, often without mediating gray. It is an inhuman landscape; people have no real home in it, which is why, as Thoma suggests, they appear so infrequently in Renger-Patzsch's photographs. Nonetheless, "the Ruhr region was the most important if not most beautiful part of Germany."35 Indeed it was the largest industrial complex in Europe.

Renger-Patzsch repeatedly contrasts the natural and the industrial landscapes of the Ruhr, emphasizing the omnipresence of factories and mines. Even his images of rural settlements are disrupted by industrial forms—if only as a narrow band on the horizon. Landschaft bei Essen (Landscape near Essen), ca. 1930 (page 26), and Zeche Carolinenglück in Bochum (Carolinenglück mine in Bochum), 1935, are cogent examples. Nature appears "naive" here in comparison to technology, though Renger-Patzsch surely wants to show that the Ruhr is not all industrial wasteland. Indeed, it was while he was living in Essen that the city created its botanical garden, and that a concern to preserve green space emerged in the Ruhr in general, to the extent that today 50 to 60 percent of the region is protected nature, as Thoma notes.36 Nature in fact becomes a signifier of wellbeing for Renger-Patzsch, for example in Margarethenhöhe in Essen (Margaret heights in Essen), 1933, which shows the street where he lived. The middle-class houses on this sedate and quiet road are covered with vines, suggesting vital, happy life within. (The full import of this imagery comes clear when the photograph is compared with those Renger-Patzsch took of the living quarters of miners.)

Renger-Patzsch's many assertions of the contradiction, indeed the incompatibility, between nature and society tend to be dry and understated, making his observations all the sharper. The point is fundamental to his photography, but those who have written about it rarely see that he implicitly uses nature to criticize society. Benjamin was too much the revolutionary optimist to recognize Renger-Patzsch's social pessimism, his articulation of what Jürgen Habermas calls the pathological desolation of modern society, in contrast to the sensuous plenitude of nature. In Industrielandschaft bei Essen (Industrial landscape near Essen), 1930 (page 30), for example, nature has been reduced to a small stream, tamed between man-made banks. Its sweeping curve is contrasted with the neatly engineered arc of a bridge in the background—an ironic contrast between nature and the perfection of which man is capable. Elevated, the bridge, a machine for traffic, dominates the picture. All the power and energy of the scene are in it. Nature is impotent in comparison.

Landschaft bei Essen, im Hintergrund die Zeche Rosenblumendelle (Landscape near Essen, in the background the Rosenblumendelle mine), 1928, adds to the contrast of nature and factory an equally ominous contrast for human beings: that between traditional culture, represented by the old timberbeamed peasant's house, isolated by the roadside—it was probably once in the middle of a field—and modernity, represented by the industrial complex. A number of photographs of this type must be considered the most directly social of all the artist's works. From 1927 to 1932—and the advent of FHitler— much of Renger-Patzsch's effort was devoted to documenting the desolation of the Ruhr, particularly as reflected in the contrast between the old residential and the new industrial order of architecture. This contrast is the theme of some of his bleakest images.

In photographs of Essen's Victoria Mathias mine made in 1929 and 1931, a modern factory complex dwarfs old buildings, suggesting their inconsequence. They belong to a useless, dead past; the factories signal the brave new world of the present and presumably the future. The difference between—indeed, irreconcilability of—past and present is hammered home in two climactic photographs of the Germania mine in Dortmund-Marten, taken in 1935. These are among the last of the Ruhr images. Here the contrast between old and new is starker and more absolute than ever, and the new's dominance of the old is unmistakable.

In some of his work from the late twenties into the thirties, Renger-Patzsch seems to be idealizing the factories. There may have been a period when he hoped that a rational new industrial and, by implication, social order would replace the tired old irrational order, as is suggested in the comparison of the old and new structures in Wasserturm und alter MalakowTurm in Essen Leithe (Water tower and old Malakow tower in Essen-Leithe), 1929. The plant in Benzölfabrik Scholven in Gelsenkirchen (Scholven gas factory in Gelsenkirchen), 1934, has a crisp, new look—perhaps suggesting the hope Hitler initially gave many Germans. Hitler would rebuild the country, ending the unemployment and inflation that had almost completely overwhelmed it in the decade after the end of the First World War. But for RengerPatzsch, the main issue was not Hitler but the restoration of Germany as an industrial power, a restoration symbolized by the new factories. (Renger-Patzsch in fact deplored Nazi anti-Semitism, and was in despair about it.37) As Thoma writes, times were not good in the Ruhr valley when Renger-Patzsch made his photographs. After an initial postwar boom there came a bust. "Already by 1926 78 mines were closed, because they were not paying, and 45,000 miners lost their jobs. By 1932 there were 1 20,000 unemployed."38

Renger-Patzsch had in fact been more or less consistently interested in the rebuilding of Germany, and especially of its industrial base, as his Kühlturm im Bau (Cooling tower under construction), 1927, suggests. He apotheosizes the idea of an enlightened new order in the mathematically clear, streamlined, generally "scientific" structure of the factory complex in his 1927 and 1929 photographs Zeche Sollverein 12 in Essen (Customs union 12 mine in Essen). Zeche Nordstern in Gelsenkirchen (Northstar mine in Gelsenkirchen), 1928 (page 40), an industrial landscape of 1929, and Gasometer bei Bochum (Gas storage tank near Bochum), 1931, offer similar idealizing, "intellectual" close-ups of parts of an industrial complex.

When Renger-Patzsch focuses on the modern factory as a thing in itself rather than as an aspect of a landscape, he typically does not simply substitute the part of the factory photographed for the whole industrial complex in standard metonymic fashion. Making the part fill the image completely, so that it becomes a pictorial whole, he suggests the incomprehensible grandeur of the complex, despite its rationality and orderliness. These photographs seem to illustrate, in however paradoxical a way, what Kant called the mathematical sublime: if the part is overwhelmingly gigantic, the whole must be all the more so. The knowledge that the entire industrial complex is rationally ordered seems unimportant, even meaningless, in the light of our awe at its seeming endlessness. In Zeche Nordstern in Gelsenkirchen and the two versions of Zeche Zollverein 12 in Essen, perspective is foreshortened almost to the point of spatial collapse, making the structure even more intimidating and exalted. Indeed, the incidental, miniature, miragelike appearance of the thin sliver of nature in the 1929 Zeche Zollverein 12 in Essen, and of the toylike railroad cars of raw material in Zeche Nordstern in Gelsenkirchen, makes transparently clear the awesome character of the factory area photographed, and by implication of the complex as a whole.

This awe, however submerged in the ostensibly documentary character and technical finesse of the photographs, suggests an optimism about modernity. Yet the majority of the photographs Renger-Patzsch made before Hitler came to power document the depression and desolation of the Ruhr, and imply that these were a consequence of industrialization. Here, Renger-Patzsch seems to suggest that modernization has had a devastating effect on human beings—indeed, that it is carried out in indifference to them; and, moreover, that it is inevitable. The photographs of the Ruhr as a human wasteland suggest the difficulty of adapting to industrialization. But the photographs glorifying factory architecture show RengerPatzsch's own adaptation to it.

If, before Hitler's accession, Renger-Patzsch responded to modernity with ambivalence, after Hitler he seemed to celebrate it, apparently uncritically, for example in his numerous photographs of modern buildings, machines, tools, and such mass-produced goods as a bottle of Coca-Cola and a cup of instant coffee—the new, modern drinks, requiring little or no human care. But at second glance these images are more complicated. For one thing, they have to be understood as in part the result of economic necessity. Having resigned his teaching position in 1934, Renger-Patzsch worked for industrial and architectural firms until he left Essen, in 1944, after the bombing raid that destroyed his archives. Thus the photographs he made during this decade are commercial, and reflect the interests of the firms for which he worked.

Renger-Patzsch's own interests showed, however, in his aestheticization of the industrial structures and products he photographed. He did not simply report their modern look; instead, he treated them as he had treated the plants and animals in Die Welt ist schön. But where his approach to living beings was celebratory—his perception of them amounting to an ecstatic fusion with them—in his thirties work, aestheticization was an instrument of depression. Whether natural or manmade, his thirties things are presented in a more depersonalized way than his twenties things. Both are equally isolated, but the glossy, cool modernity of the thirties things, such as Hitze beständige Laborgläser (Heat-resistent laboratory glasses), 1936 (page 54), bespeaks indifference rather than identification. Renger-Patzsch rarely came as close to the thirties things as he did to the twenties things. He seems to have been trying to maintain his distance and detachment in modem anonymity, which must have perfectly suited his feeling of not really existing in his own right, as an independent photographer and person. The recognition that came with his commercial commissions reflected the establishment's sense of his usefulness, not its respect for his art. Thus his sense of distance reflected a certain depression.

In a sense, Renger-Patzsch carried the depression of the Ruhr in the late twenties with him into the Nazi thirties, which initially promised liberation from it. There were no doubt good reasons for him to do so, but Renger-Patzsch came to realize, if at first unconsciously, what Hitler meant for Germany: not just resurrection as an industrial power, but the use (and excuse) of industrialism to create a totalitarian society in which difference and uniqueness were suppressed—just as RengerPatzsch's photographs implied. The Nazis encouraged a totalitarian attitude to things, so to speak, regarding them as indifferent instruments rather than as perceptual ends in themselves. For Renger-Patzsch, this was probably almost as devastating as the fact that under Nazi rule, modern industry and technology were in the service of totalitarian enslavement—a greater betrayal of humanity than the Ruhr depression, which made vulnerable human beings into wage slaves.

Renger-Patzsch's only weapon against this corruption of modernity was photography, which he used to keep alive his sense of the radical differences between things, their existential uniqueness. But he knew his photographs had to become commercial, and, worse yet, had to submit to the totalitarian attitude. His thirties things are no longer subtly and insistently differentiated—no longer really unique, that is, uniquely real. They are still lifes, in all the sinister sense of that term: they are natures mortes. Not only are they depersonalized, they lack the material weight and textural density of his twenties things, which burst with life. For the depressed Renger-Patzsch of the thirties, things died. His commercial imagery can be understood as a kind of mourning for his old attitude to them.

Thus Renger-Patzsch standardized his method of presenting objects into a matter of routine craft, a transparently technical strategy. For all their modernity, his thirties things are listless to the point of inertness, especially in comparison to his industrial landscapes of the late twenties. There is no twenties photograph as mechanical and static as the thirties photographs. Generally speaking, in the thirties Renger-Patzsch photographed not the scene of work (or if he did, it was didactically, as an object lesson) but its products, conceived as commodity fetishes. It was only after the Second World War, when he turned away from the industrial landscape and devoted himself to nature, as though seeking a healing refuge there, that his photographs recovered their power and his things their vital energy.

In these late works, Renger-Patzsch focuses on things and terrain as though to celebrate and participate in the rebirth of life after the death of German society. There is once again a sense of renewal through identification with an organic object. Renger-Patzsch did not quite identify with the commercial products and structures he photographed in the thirties, but now, once again, he let himself become part of his themes, and chose them because they were part of himself. It's true, however, that he no longer came as close to them—established an ecstatic, consummatory relationship with them—as he once did. Wartime weariness and wariness had infected him forever. He no longer expected, as he wrote in I960, anything more from "modern mass society."39

RETURN TO THE FOREST

During the half decade before 1932, Renger-Patzsch had roamed the streets of the industrial landscape at will, as his numerous photographs of them indicate. He appreciated the simple aesthetics of their curves, and acknowledged them as the arteries through which the lifeblood of the industrial revolution coursed. They symbolized its universal reach—its power to enter every life. Essen-Bergeborbeck and Landstrasse bei Essen (Provincial street near Essen) (page 31 ), both 1929, are remarkable examples, as are Alte Chaussee (Old highway) and the photographs of straight provincial highways that he took in 1927. The railroad tracks in his 1929 image of a crossing in Essen-Bergeborbeck, his 1930 images of railroad tracks on the edge of Essen, his 1931 photograph of the tracks near Oberhausen (page 33), and his 1934 photograph of the tracks in the mining area near Dortmund indicate that these too he saw as industrial streets, and, even more than ordinary streets, as paths of progress.

After the Second World War, however, Renger-Patzsch no longer traveled these roads and tracks, nor did he walk the more homely streets of the industrial world. He seemed to have left behind whatever vestige of belief in industrial and social progress he had had, as well as society as such, and made his way—escaped?—into the primal forest. In that traditional German place of refuge and recuperation he found no sign of progress, no trace of a street or of anything unsightly—only the opportunity for self-forgetfulness through communion with the elements and the elemental. Compared to the depressing realism of his Ruhr photographs, with their peculiar sense of conscience, the freshness of Renger-Patzsch s photographs of the forest belongs to the world of fantasy. His photographs of trees and stones may be among his most imaginative and lonely and personal, that is, his least realistic. While he lingers lovingly over their details, they represent his return to the paradise where details signify nothing but themselves, and as such lack answerability.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue