Part 1 of 2

“I just want to make it the most cabbagy cabbage a man ever looked at and then chopped up into coleslaw.”[1]

—Edward Weston, as quoted in The New Yorker, May-June 1946

Note: Unless stated otherwise, all photographs are by Edward Weston and both photographs and archival materials illustrated in this post are currently owned, or were owned in the past, by Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc. All photographs by Edward Weston © Center for Creative Photography [CCP], University of Arizona.

Food plays a significant role in all our lives, but for Edward Weston it was also a wellspring of creative nourishment. From the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s he found inspiration in fruits and vegetables, raising them from the ordinary to the extraordinary in a series of still lifes that rank among his most progressive and iconic works. The revelatory nature of these spare yet powerful images introduced a new mode of seeing that shocked and enthralled his contemporaries, exerting an attraction that remains undiminished to this day.

Weston sought to reduce his photographic subjects to their essence, a quest similarly reflected in his affinity for a streamlined lifestyle and restrained gastronomic preferences. Perhaps it was this predilection for simplicity in all things that, as Merle Armitage wrote, freed him to reveal the world in “its true content, its natural decorativeness or design, its most significant form.”[2]

FOOD & SUSTENANCE

An occasional vegetarian with a partiality for avocados, Weston strove for dietary balance and, like many of us, engaged in a lifelong struggle to curb his yearnings for coffee and cigarettes. As reflected in his Daybook on September 1st and October 29th 1927,[3] Weston considered such regimes beneficial for both his physical health and mental acuity:

[1 September:] The last day of August was full: nine enlarged negatives, no tests made, all satisfactory. It was a hot day too,—but I do not feel the heat these days of my simplified diet. / Not that it has ever been complicated, but lately I have eliminated all excess, and am eating two meals a day of fruits, vegetables, nuts. Meat I rarely touch,—only when dining out. Cigarettes, which I long ago thought to stop, I still use, though some reduced in number. Is it lack of will? I find myself automatically reaching for the ever-ready package, especially when nervous or excited. But one or two puffs and I’m through, half disgustedly! The day will come when the last one will be finished! / And why all this intestinal purity? To clear my mind for work! I know, absolutely, it has helped me to a more sensitive reaction and unobstructed thinking.

[29 October]: I am having coffee this morning!—the first time in weeks. It is no breaking down of my morale, rather the morning is so cold that I automatically lit the gas stove and put on the coffee pot. / I have no intention of starting coffee again, but I do miss a hot drink.”

Weston’s adherence to a simplified diet endured to the end of his life. Apparently his affection for cigarettes and coffee did as well. In June 1956, the Carmel Pacific Spectator-Journal divulged: “Even today the photographer, who recently broke himself of the tobacco and coffee habits, credits his unusually hardy resistance to irresistible Parkinson’s Disease to his preference for simple, nutritious foods. He buys raw, unshelled nuts wholesale by the 25-pound can, likes to make a meal of nuts, bananas, dates and avocados.”[4]

Alas, no amount of abstinence proved effective. Weston died of Parkinson’s on New Year’s Day, 1958.

Rarely one for elaborate feasts and complex concoctions, on 12 November 1927 (while living in Glendale), Weston wrote glowingly of a modest repast enjoyed with Bertha Wardell, a dancer friend in Los Angeles who posed for some of his finest post-Mexico nudes: “Bertha returned with me for supper: aguacates [avocados], almonds, persimmons, dates, and crisp fresh greens. A steak is sordid beside such food for the Gods.”[5]

In San Francisco a year later, Weston not only expounded on the simple meals he and his friends considered a “banquet,” he extolled the merits of his bootlegger! Confiding to his Daybook on September 10th and October [19th] (entry undated) 1928,[7] Weston wrote:

[10 September:] Supper here: that was the unanimous decision. The best restaurant pales before our banquets. Avocados,—Brett found at 5 cents each!—an enormous Persian melon, crisp lettuce and peppers, swiss cheese, rye-crisp, comb honey, kippered cod: all for less than $2. Who would eat out? Not since Mexico have I had aught alcohol on tap for my friends,—I never drink alone. My bootlegger calls every Monday to inquire for my health and suggest that I may have run out of gin over the week end. The order is delivered promptly to the front door, as casually as the grocer might bring a bottle of vinegar. This town is wet! / My bootlegger, who also supplies thirsty U.S. Senators, who vote dry, is a tall venerable Dutchman: always immaculately groomed, with high stiff collar, grey spats, gloves and stick. Before the important question, am I dry?—we chat for awhile,—current events, even art. His call is a social event, though he is a bit too sociable.

[19? October:] … We served one of our typical meals: a dish of avocados,—five of them, which may have appeared extravagant for a poor artist but cost only 10 cents each, a big bowl of cottage cheese, rye-crisp, gorgonzola, plenty of greens, muscats turned almost to raisins, and coffee with honey.

Even his own birthday celebrations failed to diminish Weston’s disinclination for rich food. In Carmel on 25 March 1930,[8] he bewailed:

A chicken dinner for me last night with all the trimmings of a usual American dinner, mashed potatoes, gravy, etc., in honor of my 44th birthday. Chicken to honor a vegetarian! It looked good I must say, this festive table, but the eating of it was disillusionment,—I would have prefered [sic], and many times over, a fine avocado a crisp salad, and for desert, Ramiel’s [McGehee] ambrosia,—oranges, fresh coconut, and honey—instead of pudding.

Such restraint seems not to have held sway during his time in Mexico, however. As his Mexican Daybook entries make clear, it was not unusual for Weston to appreciate ample—often ethnic and meat-laced—dishes washed down with an alcoholic beverage. On 8 December 1924,[9] he described a meal enjoyed in Mt. Ajusco:

Early breakfast in Las Tres Marías,—then a morning tramping the hills around Mt. Ajusco. Lunch was delicious: Chicharrones [fried pork belly or rinds], cheese, mescal, and solid food it was for hungry people. Four generous drinks of fiery mescal did not phase me, yet at times a glass of wine will turn my head. I worked some with my Graflex, interesting cloud forms, surprising at this time of year. The landscape fine too. As to results I am in doubt,—the festivity of our party prevented concentration.

He clearly favored vivid, flavorful cuisines over the traditional New England fare of his forebears. On 2 April 1924[10] he praised a dinner enjoyed at the Mexico City home of friends Rafael and Monna Sala:

A good supper tonight, the Salas have a most excellent cook, spaghetti rivaling Tina’s [Modotti] and codfish Spanish style which I could not but compare to the simple creamed codfish or codfish “balls” (what a name) of my New England ancestors: the codfish a la española, a racy, piquant dish, and colourful to the eye: that of New England a staunch, wholesome, unimaginative food, cooked to be consumed.

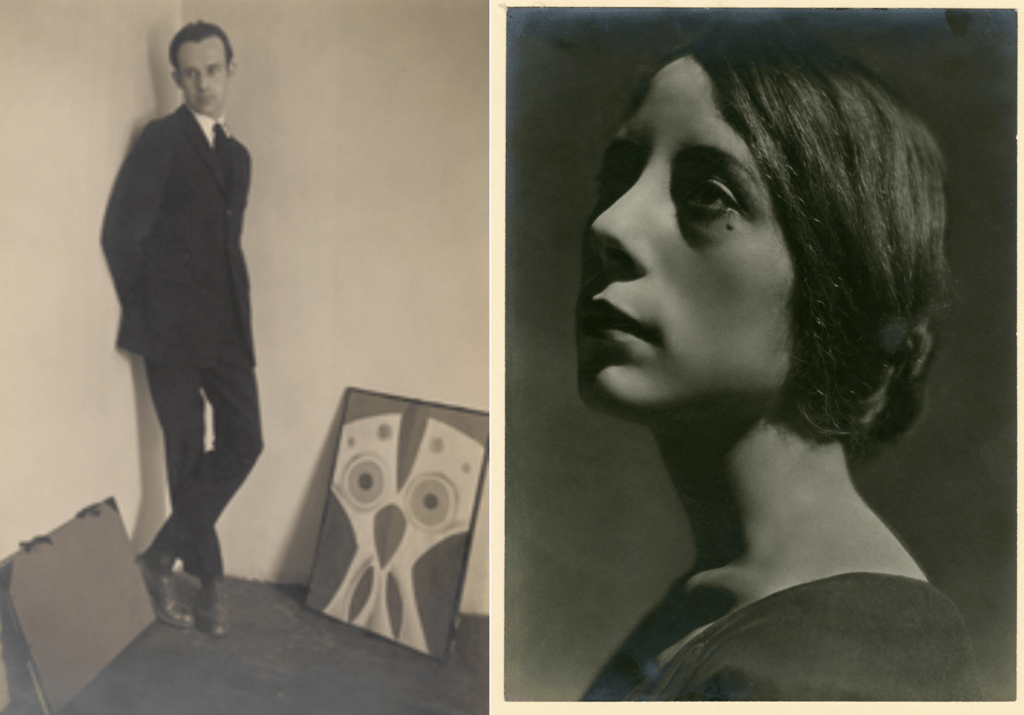

Right: Monna Alfau Sala [Texidor], 1924, Vintage matte surface silver print.

Finally, there are these accolades, recorded in Guadalajara on 4 July 1926[11]:

Victoria [Marín] cooked us wonderful meals,—real banquets. Caldo [broth] with aquacate [avocado] sliced in, chiles rellenos, pipiano de pollo,—a sauce of pumpkin seeds over chicken, fruit salad of guayava [guava],—delicate and refreshing. And then another well remembered meal,—supper at Valentina’s in the outskirts of town. Valentina was a famous cook, a magnet for all classes. Food was the thing. Formalities she would not be bothered with. We asked for knives and forks,—she had none—only food!— and we had hands.

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.120.13)

Although avocados reigned supreme in Weston’s culinary pantheon, ironically, he seems not to have photographed them (at least that I have found). Indeed, his enthusiasm for this favored fruit was so great that, whether at home or on the road, they were never far from hand. In its review of Weston’s 1946 Museum of Modern Art retrospective, The New Yorker magazine observed: “Edward Weston, two hundred and sixty-one of whose photographs of such things as sand, cats, eroded rocks, parts of cypress trees, and vegetables constitute a current one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art, is here on a visit from his California home, and a few days ago we buttonholed him. He had a paper bag full of avocados on his lap during our talk…”[12]

FOOD & FROLIC

Weston valued essence over excess, but did not lead an ascetic existence. He was warm, unassuming and a congenial host who appreciated intellectually stimulating friendships and vibrant experiences. In spite of a penchant for healthy foods, he enjoyed the occasional tipple and relished a spirited party.

At one such event, a costume extravaganza thrown at Weston’s Carmel studio on 21 September 1929, Weston and Myrto Childe, as King and Queen of the Revels, held court attired head to toe in vegetables! Weston wrote that his crown “… was a hollowed-out cabbage with jewels of onions and radishes” and he “wore a vermin-trimmed [sic] robe and a necklace of green peppers, onions and a cucumber pendant.”[13] Childe’s equally delectable ensemble was described by The Carmel Pine Cone on 27 September[14]:

Myrto Childe, the entertaining chef at the Mona Mona, appeared at the Edward Weston masquerade party Saturday night in a most elaborate costume decorated with vegetables. A string of green peas hung from her neck, with nice pink carrots and red beets trailing from her velvet skirt. ‘There’s method in my madness,’ she said. ‘I don’t believe in wasting anything. Come on down tomorrow—we’re going to have vegetable soup.’

An earlier account in the 25 September issue of The Carmelite[15] revealed:

Edward Weston’s fancy dress party Saturday evening was what The Carmelite’s society reporter (if it had one) would describe as a most enjoyable and successful affair. It started out to be a farewell gathering for Ramiel McGehee; before it was over it had become the social event of the season. / The Weston studio was transformed for the evening into an audience chamber, with the King of the Revels (Edward Weston) and his Queen (Myrto Childe) holding court. Impressively garbed emissaries represented European, Asiatic and the vegetable kingdoms. It was a motley and colorful grouping: jesters and gestures; a court poet and peasants galore; lavender-scented prints and futuristic projections… / Myrto Childe, Frederick O’Brien and John O’Shea judged the costumes…

In attendance was an impressive list of the area’s artistic doyens, among them Sybil Anikeeff, who wore a “green pepper” outfit that may well have been an homage to her friend Weston’s much discussed photographs. The Carmelite article also disclosed “… a list of guests, gathered from sources known to be reliable” along with the caveat: “Omissions, if any, are due to lapses of memory on the part of trusted informants.” Among the cavalcade of revelers were David and Iris Alberto, Vasia and Sybil Anikeeff, Mary Bulkley, Dene Denny and Hazel Watrous, Helmuth Dietjen [Deetjen], Jeanne d’Orge, Martin and Sarah Flavin, Herbert Heron, James Hopper, Edward and Ruth Kuster, Francis McComas, Sonia Noskowiak (dressed as a “juvenile”), John and Molly O’Shea, Tilly Polak, Fredrik Rummelle, Pauline Schindler, and Roger Sturtevant (costumed as an “Ultra-modernist”!). Ramiel McGehee served as Master of Ceremonies and Fritz Wurzman as the “assistant Master of Ceremonies.”

Equally revealing are Weston’s Daybook entries from September 20th, 26th and October 2nd [16]:

[20 September:] … A big mask party planned for tomorrow night, which Ramiel is engineering. Over fifty invited from all walks of life: Pebble Beach and Highlands Society to Carmel Bohemians! I am in the excitement only as a spectator: until the night!

[26 September:] … every one seemed to be having a good time,—and without alcohol! The morning after, viewing the room carpeted with confetti and serpentines, fragments of costumes, discarded masks, floors stained with spilled punch, a great log gone to embers in the fire place, I felt like writing of the grand march which Myrto and I led, as King & Queen, down Ocean Avenue, astonishing the natives, of the many amusing, bizarre or exquisite costumes, of the overflow of amorous couples found in our nearby house, of Ramiel’s directing, and of Sonya as a modiste,—but most of the details will live as memory only, for I have no time! / …

[2 October:] … Myrto, my queen of five feet eleven, made an adorable consort for me of five feet five or so. Enthroned in state as rulers of the vegetable kingdom, all who entered were made to kneel and kiss our hands. If they refused, or hesitated, ‘Off with their heads.’ There were innumerable executions by way of the saw! / …

Weston’s indomitable party spirit prevailed for most of his life, curtailed only—beginning in the late 1940s—by the progression of his Parkinsons Disease. In 1948, Weston’s friend, the photographer and filmmaker Louis Clyde Stoumen, recalled one such Carmel gathering in his Photo Notes article, “Week-end with Weston”[17]:

… The week-end at Carmel featured a birthday party for Weston, attended by two or three dozen friends, sons, daughters-in-law, grandchildren and gate-crashers. There was a huge bowl of spiked punch, dancing to the music of an old phonograph, and much easy spirited conversation. Weston’s vigorous friendly presence did at least as much to warm his guests as his punch and his fireplace. The party broke up about 1:30 in the morning, long past his usual farmer’s bed-time. …

FOOD & INSPIRATION

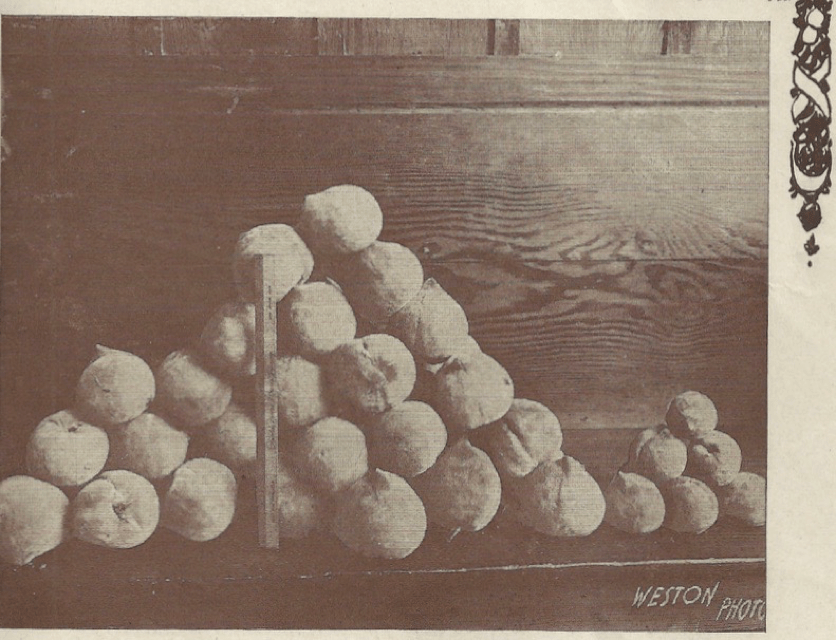

Of course, photographic still lifes, not parties and meals, are what spring to mind when we think of Weston and food. Perhaps his earliest foray into fruit and vegetable compositions was a commercial shot of peaches made for the 1915 promotional booklet Tropico, The City Beautiful.[18] Horticultural abundance may have been the impetus behind this assignment, but already apparent is Weston’s eye for line, form and essence—hallmarks of his mature still lifes a decade or so later. Here, the characteristic downy skins and irregular contours of the peaches are accented by light raking from the right, enhancing both the fruit, the shadows between them, and the similarly patterned grain of the wood paneled background. The imbalance of the two groupings of peaches, apparently meant to emphasize the superiority of the larger, Tropico produce on the left, together with the illumination and sense of tactility, lend interest to what might otherwise have been a purely didactic presentation.

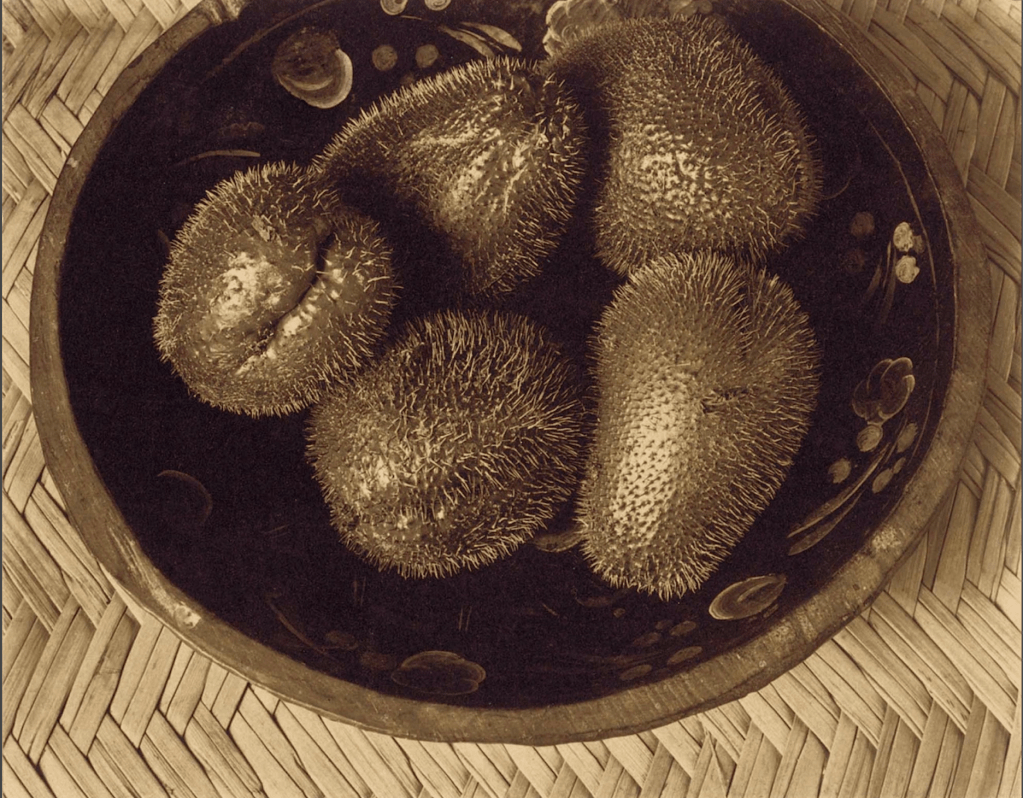

By his own estimation, Weston’s first bonafide still lifes were created in Mexico in 1924. Among them was a photograph of chayotes (a type of squash) he described in his Daybook on 30 September 1924[19]:

Several negatives printed are new, made during this last cloudy week when I turned to my camera for diversion and consolation. Still-lifes they are, and pleasing ones: two fishes and a bird on a silver screen; head of a horse against my petate; chayotes in a painted wooden bowl. The animals of course are from the puestos [market stalls]. … These still-lifes, strange to say, are the first I have ever done; and feeling quite sure they number among my best things, I would comment on how little subject matter counts.

A bowl of fruit was hardly new to the still life genre, but Weston’s close, sharp focus introduced a fresh, intrinsically photographic approach to this time honored subject. With startling clarity, he presents light drenched chayotes shimmering amongst a complex array of contrasting textures, shapes and patterns. An overall flattened perspective emphasizes the full dimensionality of the fruit and an engaging asymmetrical tension is achieved by cropping the top of the bowl. This is a far more sophisticated photograph than the commercially rendered peaches of 1915.

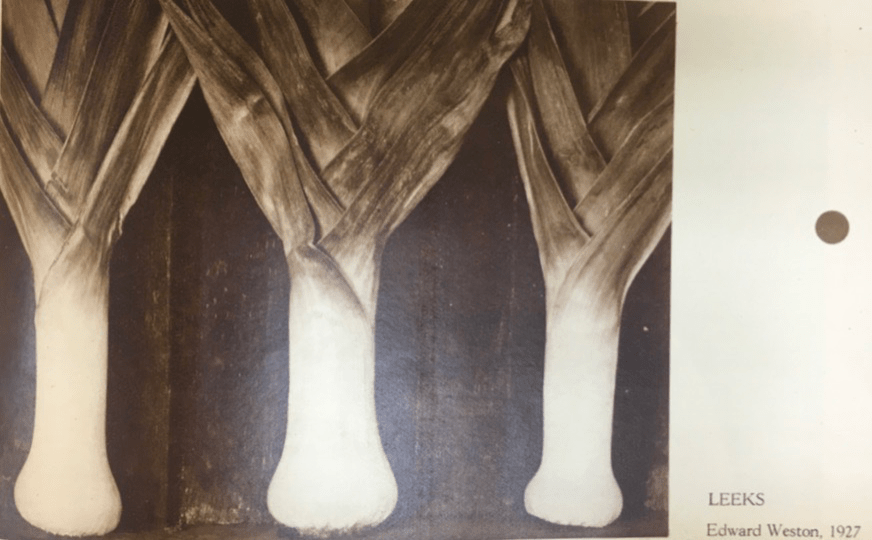

Still, it wasn’t until Weston returned home from Mexico to Glendale (formerly Tropico) in late 1926 that he made an appreciable shift to still lifes. The joint constraints of studio photography and renewed family life were surely practical factors, but even more influential were the effects of the vibrant artistic milieu he’d experienced in Mexico. Equally relevant was his introduction to the work of such fellow California artists as Henrietta Shore, whose strong, abstract paintings and collection of nautilus shells would inspire some of Weston’s most enduring images.

(Sotheby’s Photographs From the Collection of Joseph and Laverne Schiezler, New York, 10 October 2005, Lot #5)

(Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Boeckman Mayer Family Fund of the Foundation for the Arts; Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art; 2015.24.FA)

Weston grew increasingly enthusiastic about his new studies, writing on 4 April 1927[20]:

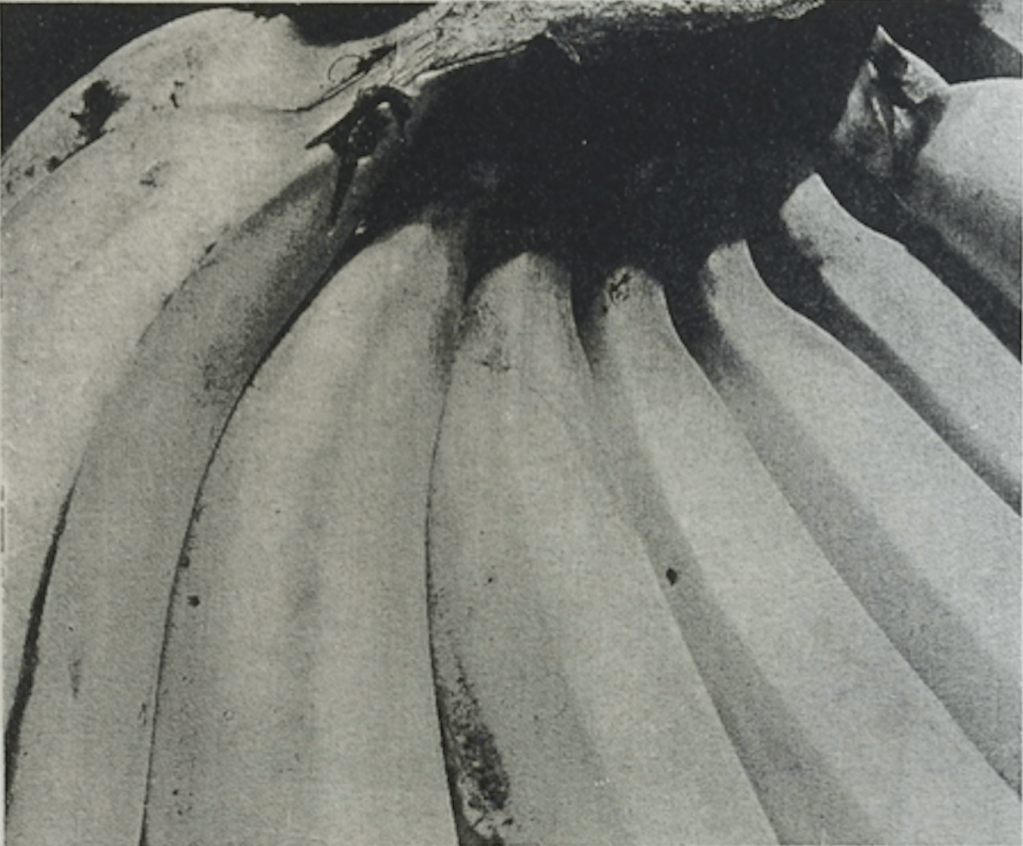

5:00 a.m, though I was awake at 4:00, with my mind full of banana forms! How exciting they are to work with! I am torn between two new loves—bananas and shells. I shall repeat the same arrangement of bananas, an orange and my black Oaxaca olla [a ceramic cooking or storage jar], and do many more besides.

The result is an elegant interplay of tones, textures and complementary geometric shapes. A circular orange, with its segmented end, textured peel and reflective surface, sits at the base of an upswinging arc of smooth skinned bananas, their bright surfaces punctuated by dark, irregular patches. Behind them rises the deep black oval of the olla. Weston achieves an absorbing, harmonious balance by setting this assemblage against two bisected rectangles—a subtly reflective table top and a lighter, gradient lit background.

(The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XM.860.4)

Not surprisingly, Weston’s creative fervor resulted in increased productivity. On 10 September 1927, he wrote: “I have been printing: have ten new prints,—three shells, a gourd, the rest vegetables. I like especially the radishes and pepper, the swiss chard, and one of the shells.”[21]

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.252.103)

Photographing perishable subjects naturally gave rise to all manner of tribulations. On 6 April 1927,[22] Weston recorded one such mishap with bananas:

I can foresee that bananas, even as a bouquet of posies, are to be elusive material if I wish to repeat a negative: they too wilt and change, and there is yet another danger, which concerns the afternoon appetites of small boys: the last bunch was consumed before I had thought of hiding or warning. Brett bought another bunch, but the grouping was so different I could not carry out my original idea. / Nevertheless I attacked the problem from another angle and have a new negative worth finishing. I am not through with bananas: and I shall watch the markets for other fruits and vegetables. …

The inherent edible/perishable conundrum remained a constant. On 1 August 1930,[24] Weston meditated on the dilemma of peppers:

But the pepper is well worth all time, money, effort. If peppers would not wither, I certainly would not have attempted this one when so preoccupied. I must get this one today: it is beginning to show the strain and tonight should grace a salad. It has been suggested that I am a cannibal to eat my models after a masterpiece. But I rather like the idea that they become a part of me, enrich my blood as well as my vision. Last night we finished my now famous squash, and had several of my bananas in a salad.

[For detailed information on Weston’s study of peppers, see my initial post of 4 September 2019 titled Pepper No. 30.]

Weston’s focus on still life intensified after his move to Carmel in January 1929. That he held food in equal esteem with the rocks, trees and landscapes he was also photographing is clear from this Daybook entry of 14 November 1930[25]:

… I have only discovered unusually important forms in nature and presented them to an unseeing public. I have had time and again persons tell me, “I never go to a market now, without looking at the peppers, or cabbage, or bananas!” And even they bring me vegetables to work with, as the Mexicans used to bring me toys. So I have actually made others see more than they did. Is not that important? When I work in the field with rocks, trees, what not, I think that this is my important way: then comes a period of “still-life” which excites me equally. So the best way is not to theorize, but do whatever I am impelled to do at the moment. I have always had the faculty of seeing two sides, positive and negative, to a question. No sooner do I say “no,” than out pops “yes.” Of this I am sure: the intimate “close-up” study of single objects has helped my work outside. As to Jean’s remark re implications of growth—If I get into my work that very feeling of growth—livingness—I am deeply satisfied.

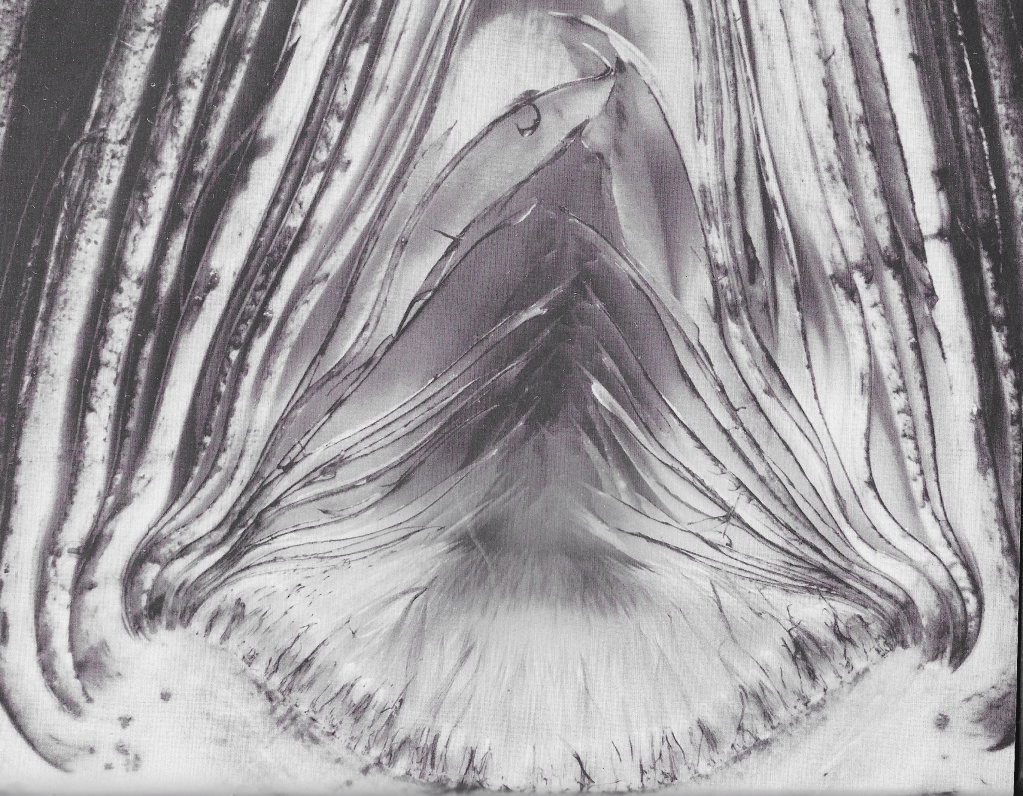

To Weston, these were not simply artful compositions of static objects, they were the essence of organic forms made manifest. On 23 April 1931,[26] he wrote in his Daybook:

For the first time in months, I am excited to work, and by “still-life,”—though I do not like the designation still-life, a misnomer for my most living artichokes, peppers, onions, cabbage! Cabbage has renewed my interest, marvellous [sic] hearts, like carved ivory, leaves with veins like flame, with forms curved like the most exquisite shell. These forms—which Sonya [Noskowiak] discovered—came to me, coincident with a letter from Alma Reed in which my next N.Y. Exhibit is discussed! [Weston’s second solo Delphic show, in February–March 1932]…

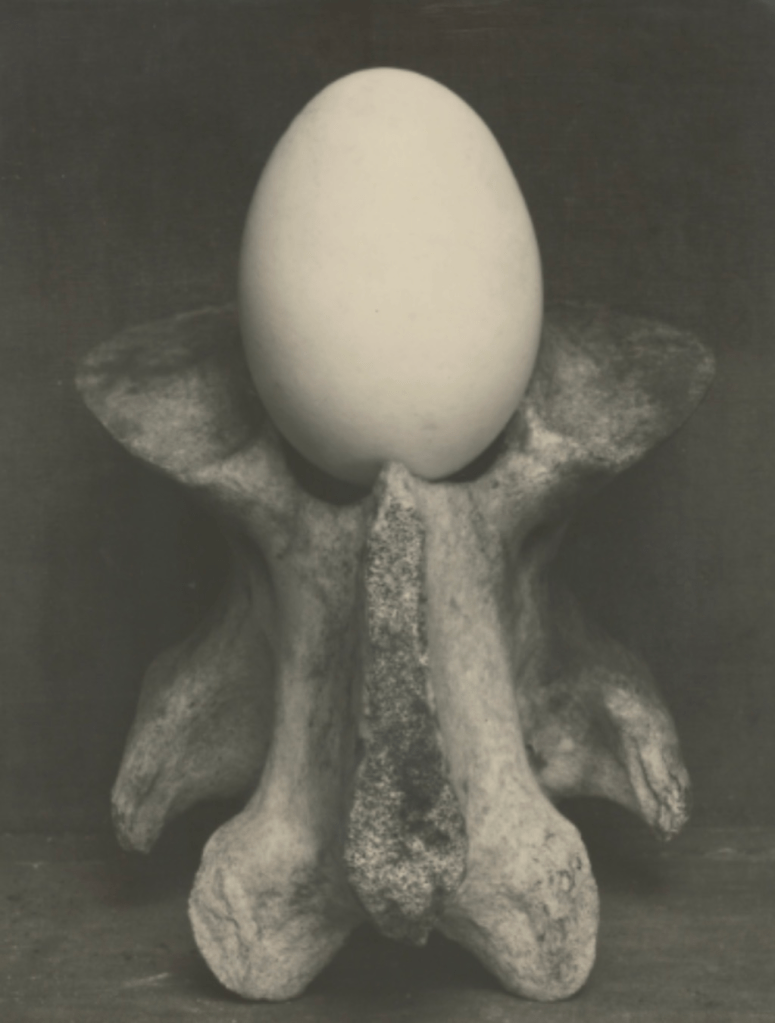

Weston also combined food with disparate yet complementary elements to create luminous studies in contrasting forms and textures. For example, in 1930 and 1931 he paired the smooth, lustrous ovoid of an egg with the rough irregularity of bone.

(Sotheby’s, Photographs, 7 October 2016, Lot 25)

He preferred the later photograph, writing on 23 February 1931: “… a new and much finer version of the egg and bone. I placed an egg upon my sea-bleached seal bone, in the course of experimenting one rainy afternoon: but this was not at all what I started out to do,—I have quite forgotten my primal impulse.”[27]

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.120.2)

Another masterful composition—an impressive essay in shapes, surface and light—is a 1930 arrangement of eggs, an egg slicer and aluminum baking dishes, about which Weston wrote on 18 June 1930[28]:

…Irving and Ruby [unidentified] had a fascinating cutter for slicing hard-boiled eggs which they gave me to work with. The taut wire strings for slicing give it the appearance of a musical instrument, a miniature harp. I put the hard-boiled egg, stripped for cutting into it, a couple more eggs were commandeered to balance, and two aluminum baking dishes, the halved kind, made to fit together in a round steamer were used in back. Result,—excellent…

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.151.8)

Jerome Klein, an art critic and proponent of Modern art, praised this photograph and other Weston still lifes in an article published on 28 October 1930 in the Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World.[29] Weston valued Klein’s appraisal, quoting a brief excerpt in his promotional brochure of 1931.[30] Klein’s review reads:

Hard-boiled eggs and a wire slicing device—not very inspiring material, one might say—yet out of it Edward Weston has created a masterpiece in the art of photography. All of which is a reminder that one of the fundamentals of artistry consists in a selection of those textures related to the medium in which one works, a qualification which Mr. Weston possesses to a high degree. Under his masterful handling the egg loses its culinary homeliness and becomes a form whose purity of contour is impeccably translated into light. And the deadly slicer becomes a symbol of that machine function which artists try so frequently to embody in their conceptions these days. / In a series of other plates the motives are green peppers, whose voluminous forms with their restless muscularized contours suggest nothing so much as a pair of titanic wrestlers come to grips. A bunch of bananas lying robotlike forms a striking rhythm. And finally there are the extraordinary compositions of Kelp, by far the most intricate and certainly among the most articulate of all, tho the writer’s preference runs to the disembodied spirits of the hard-boiled eggs. / Mention should also be made of the splendid portraits of Orozco, Robinson Jeffers and the assassinated Mexican senator, Manuel Hernandez Galvan, included in the Weston exhibition at the Delphic studios.

FOOD & ACCLAIM

1930 ushered in increased exposure and acclaim for Weston’s still lifes. In October–November he enjoyed his first solo show in New York City—at Alma Reed’s influential Delphic Studios gallery. Of the fifty photographs on the exhibition checklist, twenty-four were of shells, vegetables, fruit, bones, and eggs with egg slicers.[31] Frances D. McMullen gave voice to the public’s surprise at Weston’s choice of still life subjects in her perceptive review for The New York Times Magazine on 16 November 1930.[32] Titled “Lowly Things That Yield Strange, Stark Beauty,” it reads, in part:

The spectacle of the market stall dumped into the art gallery now gives New York pause.. … / On the market stall green peppers writhe and shine, cabbages sit sullen and stolid, celery shakes out ruffles. And there are people who stop to admire, as long as the artificial dew of refrigerated freshness holds the forms crisp and firm. Who would think of peppers, cabbage and celery for their looks alone? Who would dream of posing them before the camera’s eye in quest of new revelations of beauty? Who would essay to draw from them, by photograph, messages of such import that even artists would acclaim the experiment? / Edward Weston has thought of it and has done it, not only with vegetables but also with other usually prosaic subjects, as his fifty photographs on view at the Delphic Studios attest. It is through him and his camera as a medium that one is treated to the extraordinary sight of lowly things just as they are, untranslated by the magic of crayon or brush, elevated to the sphere of art. / With all the ardor of the modernist, Mr. Weston has joined in the search that animates all modern art, the quest for ‘significant form’; but he has gone about it in a way utterly different from the painter, the sculptor, the sketcher. … / He discovers them on the pantry shelf, in the scallops of a Summer squash; in the yard, in a bit of soil or a handful of pebbles; by the sea, in a tortuous knot of stubborn kelp or the stately spiral of a shell. They are foundation shapes and structures of nature’s creating, scattered everywhere for man to perceive and reveal, if he can. / Seven green peppers hung on a gallery wall are … ‘more than peppers,’ in the Weston phrase. They are seven varied expositions of composition and line, of mass and proportion, of texture and form. … / A bunch of bananas becomes a study in simplicity of line; a halved cabbage is a revelation of intricacy of design. The slender upright trough of a celery heart, bending slightly from firm, massive base to flame-like tip, might be a latter-day memorial shaft. An egg slicer, opened and set at an angle, suggests some gaunt structural pattern. … / … / It is the other things, though, the vegetables, the refuse, the roots, that hold his heart. It is they that signify what he wishes to stand for in his art. And it is they, in his hands, that led a recognized authority, Dr. Arnold Genthé, viewing his New York exhibition to exclaim: ‘These open up entirely new paths to photographers.’ But, as the blazer of this new trail himself acknowledges, Edward Weston is not for those who do not find beauty in cabbages, plumbing fixtures and smokestacks, as well as in clouds, faces and flowers.’

(Christie’s, Photographs, 6 October 1998, Lot 197)

Margaret Breuning’s review of the Delphic show in the New York Evening Post on 25 October noted appreciatively: “… Mr. Weston has photographs in this collection of artichokes and eggs, bananas, and many other familiar objects in which he seems to have the uncanny insight to discover beautiful structure, striking linear design, rich nuances of color and varieties of texture. …”[33]

Subsequent iterations of the Delphic show toured throughout 1931, appearing at the Grace Horne’s Galleries in Boston (April–May), the Brooklyn Botanic Garden (May, revised and titled Forty Photographs of Plants and Plant Parts), the Walden Gallery in Chicago (June), and the Gallery of Fine Arts in Columbus, Ohio (October).

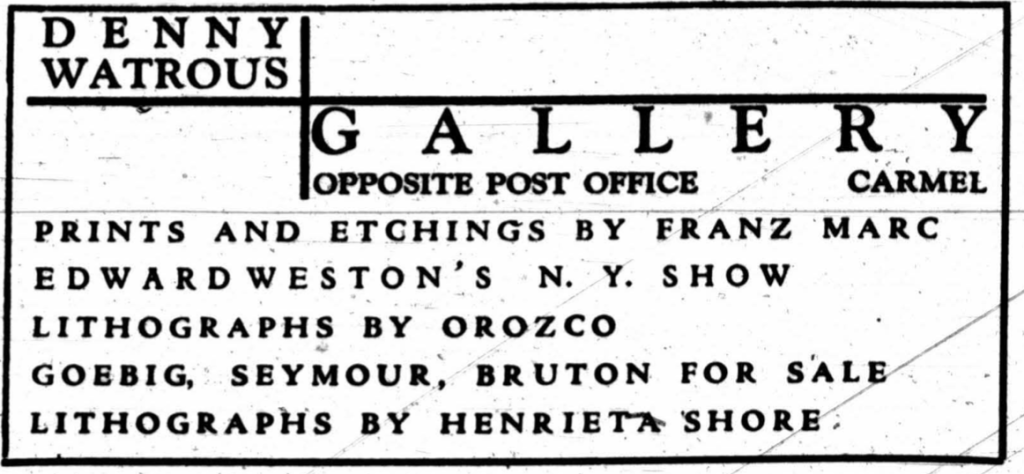

On the West Coast, the Delphic show was duplicated for concurrent exhibition at the Denny-Watrous Gallery in Carmel from 25 October–6 November 1930, thence to the Vickery, Atkins and Torrey Gallery in San Francisco (December) and the Fine Arts Gallery in San Diego (May–June 1931).

This insightful review of the Denny-Watrous show, written by Harriet Brown Seymour, appeared in The Carmelite on 30 October 1930[35]:

To be able to accept the gift—yours for the taking—offered you in the Weston exhibit at the Denny-Watrous Gallery, this week, you must take with you, when you go, not only your eyes but what Walter Lippman in his definition of ideals, calls “an imaginative understanding.” / For Weston’s goal is, I infer, not only to image in sharp clearness what is at first glance apparent, but to reveal through a penetrating lens in the hand of an eager prophet, a visionary scientist, a much-seeing artist, more than the obvious. / Not necessarily more only in conceptive content, but more as I understand it, of elemental physical detail. / What at first impression seemed in Walt Whitman a careless, casual, catalogue of commonplaces, considered thoughtfully revealed a beauty of relationship that bound these thoughts and things into a perfect pattern, a restful harmony. And here’s another list: shells and stones, and vegetables! We see a common eggplant on a plain white plate, but neither common nor plain apply to, or describe, the circle design; (made with these materials by the hand of the artist) tone circles so full of contrast in line and color as to make a perfect rhythm, therefore a deep quiet. Perhaps this achievement in balance between motion and rest, through rhythmical movement in design or pattern, is the reason artists call these studies “Still Life.” Cut a cabbage in two, catch its beauty by the light through the lens and we remember the fantastic fairy pattern in a marble column in the Mormon Temple. And in the heart of an artichoke there’s a design for the rhythm of growing, we hear it pulsing and throbbing, as we hear the beating of wings in Brancusi’s “Bird in Flight.” / To write something descriptive about a work of art, is to interfere with your power to think something on you own, at the behest of the suggestive power contained in the artist’s achievement in formulating his vision, his poetic content, his philosophic interference. / Passing along the line of these pictures, some alchemy will surely change the onlooker into an observer, the observer to the man of vision, the visionary to the man of inner understanding—The Rich Man.

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.268.224)

Alma Reed continued to share and generate publicity for Weston’s work, maintaining a selection of his photographs for ongoing exhibition.[36] A pictorial piece in the 15 May 1932 issue of The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Magazine for Women[37] was comprised entirely of vegetable studies provided by Reed. The brief accompanying text reads:

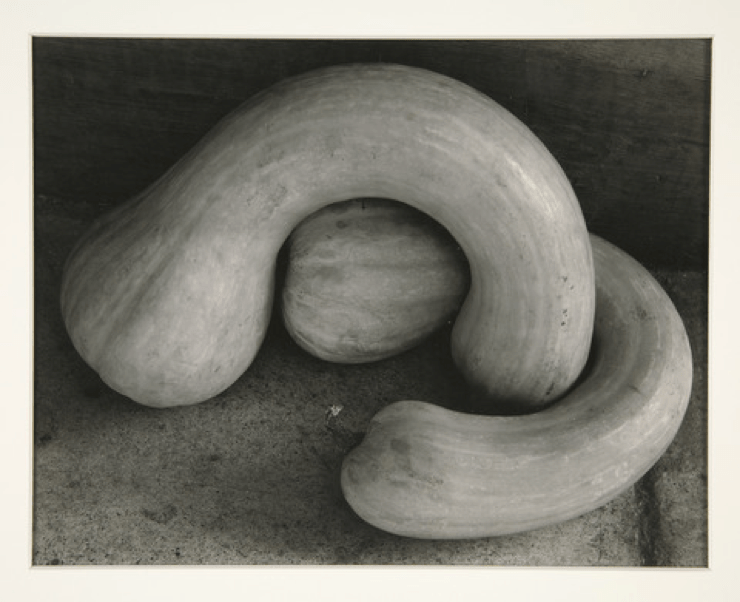

To the housewife the lowly cabbage, the saucy pepper and the more aristocratic squash have utility—so many vitamins, so much nourishment. / But to Edward Weston, photographer at Carmel-by-the-Sea, Cal., whose photographs are reproduced on this page, they express the simple, exquisite beauty of Nature. / No delicate fashioning in alabaster by a sculptor’s deft hands could be more beautiful than the symmetry of the green peppers at the right, and top left of the page. Note, too, the lines and movement of the cabbage when halved, at top right of the page, and of the cabbage leaf, lower left. The table squash, at left and lower right is beautiful in its simplicity.

Weston’s fruit and vegetables appeared in numerous shows and publications from 1930 on. The seminal exhibition Photography 1930, organized by Lincoln Kirstein and first shown at the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art in November 1930, included ten Weston photographs, four of which were peppers, a halved artichoke, and bananas.[38] Once again, Alma Reed was involved. A letter dated 12 November 1930 to Weston from Sophia R. Ames, Secretary of The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art,[39] notes:

… I enclose a catalogue of our exhibition of Photography. We were very glad to have some of your photographs, and they have been very particularly admired. Thank you so much for sending them, and for sending them air mail so that we got them in time. The whole exhibition is going on to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn. when it leaves here at the end on [sic] November, and Miss Reed at the Delphic Studios tell [sic] me that I may send your things on there and have them return them to her at the end of their show. I also entered them as lent by the Delphic Studios at her request. / …

Also in 1930, Merle Armitage published a portfolio of thirteen Weston photographs, four of them vegetables, in the June issue of Touring Topics.[40]

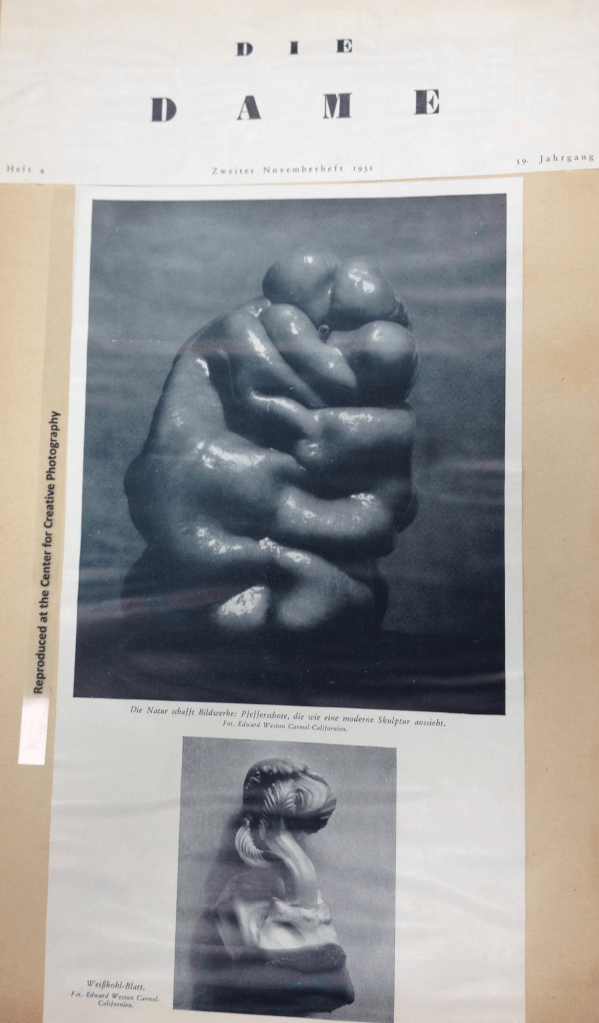

Appreciation for Weston’s food studies extended to an international audience as well, as exemplified by this two-photograph pictorial in the November 1931 issue of the progressive German women’s magazine, Die Dame. The piece was published, without related text, under the heading, “Die Natur schafft Bildwerek” [Nature creates sculpture].[41]

(Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona)

Less than a year later, on 5 June 1932, these same two images appeared along with five additional Weston photographs (possibly provided by Alma Reed) in an article titled “Naturen Som Billedhugger” [“Nature As Sculptor”] by Louise Bjørner in the Danish publication Politiken Magasinet.[42] As the article makes clear, Bjørner met with Weston at his home in Carmel and she quotes him extensively. Her article reads, in part [translation provided by Thor Mednick, an art historian specializing in Scandinavian art]:

… There [California], Weston found his ideal workplace and took the pictures that are featured this month in his second New York exhibition [Delphic Studios, 29 February–13 March 1932]: these peculiar photographs that cause people to stop in their tracks and wonder aloud, ‘Is it Futurism, Symbolism, a tonal fantasy, fairy tale illustration, or what?’ / ‘None of these,’ answers the artist. ‘They are photographs of reality, without retouching, without staging, without artificial light or any other such humbug. … All forms and lines can be found in existence. No artist has ever introduced anything new. And it would be impossible to do so, anyway, because we cannot go beyond life’s limitations or parameters. All is given, we have only to receive.’ / … ‘We should not attempt to perfect Nature, but rather strive to reveal it.’ … In another period, he took pictures of bananas, toying with and manipulating them in a quest for the right view. That continued, until the day his sons freed him from such problematic experiments by eating the bananas! / Edward Weston searches for the most stringent objectivity in all of his motifs. He doesn’t just present the form and the light; one gets a palpable sense of the material … A bell-pepper of Weston’s looks exactly like a grumpy, grey-bearded troll; pebbles, lying in the mid-day sun on a little stretch of beach, seem like little tots out for a walk. An egg-slicer [for 25 øre (one-quarter Danish Crown, i.e., cheap)] becomes an apotheosis of machine engineering. Edward Weston smiles at our surprise. Nothing is further from his mind than to present things as anything other than what they are. / A Visit with Edward Weston / We walk together through his atelier in Carmel. It’s as plain and peaceful as a priory cell. He shows me his treasures, thick portfolios full of the fruits of many years’ work. … / Outside the window, the peaceful ocean rolls in long, smooth drafts toward the rocky shore. On the cliff, stripped and weather-beaten cypress trees stand at a tilt and stretch their white branches in toward the land. Edward Weston is the only one of the colony’s artists, however, who never worshipped those cypresses – like H.C. Andersen [Hans Christian Andersen, whose tales she compares with Weston’s photographs elsewhere in the article, hence the comment about trolls and tots], he showed the world greatness and wonder in little, mundane things.

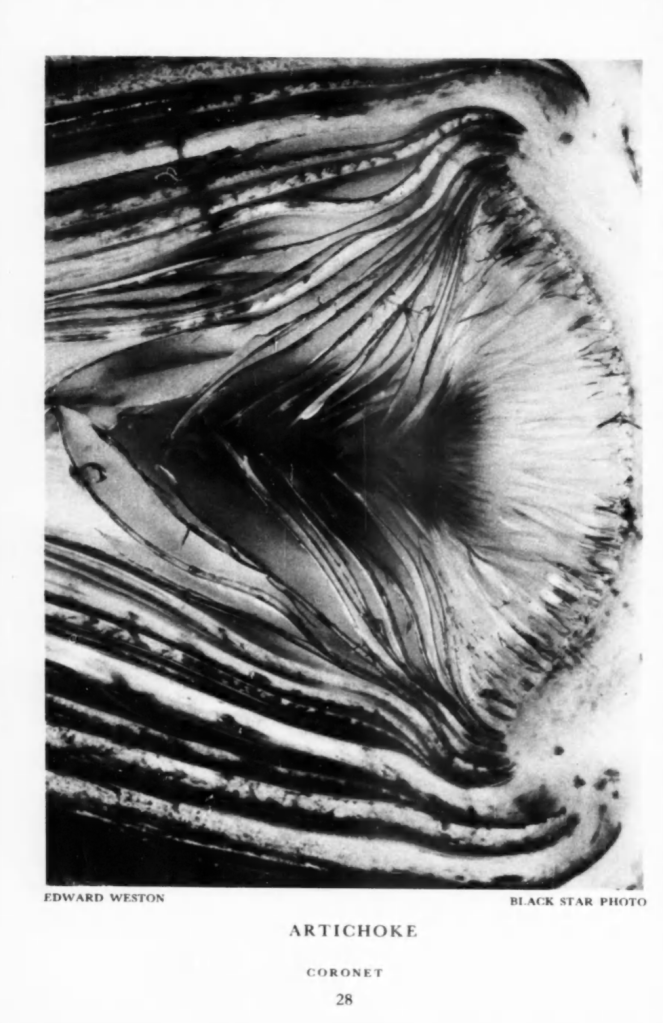

Among Weston’s most startling abstractions are his intimate close-ups of halved or segmented vegetables. In its premier issue of November 1936, Coronet magazine published the following three photographs, without comment, in its “Pictorial Features” section: Cabbage Fragment, 1930, Onion Halved, 1930, and Artichoke Halved, 1931 (flipped vertically).[43]

Despite the accolades and attention, Weston bemoaned how misunderstood were many of these compositions. Critics and the public often read into them symbolism that Weston adamantly insisted was unintended—these included sexual references, parallels to modern sculpture, and anthropomorphic interpretations. Even Weston’s friend Ansel Adams, although less than enthusiastic about the vegetables, voiced dismay over the symbolic readings made by others. In an article published in the December 1931 San Francisco periodical, The Fortnightly,[44] Adams wrote, in part:

Since the beginning of photography scarcely a dozen workers have fully realized the possibilities of the camera. Atget, Stieglitz, Strand, Steichen, and Weston, and a few others, have sustained photography in the realm of pure art. The work of Edward Weston represents a distinguished and specific phase of photgraphic [sic] expression; his prints testify to his knowledge, taste and perception as an indisputably fine artist. / … / Weston is a genius in his perception of simple, essential form. … one may occasionally question the highly decorative aspect of some of his work on the grounds of austere aesthetics. Probably the thought of purely decorative effect seldom enters his mind, but he often makes his objects more than they really are in the severe photographic sense. While succeeding therein in the production of magnificent patterns of definitely emotional quality, he occasionally fails to convey the prime message of photography—absolute realism. In the main, his rocks are supremely successful, his vegetables less so, and the cross-sections of the latter I find least interesting of all. … / The simplification of form which is apparent in Weston’s work opens the way for interesting comment, some of which, however well meant, can react unfavorably on his entire work. He is often accused of direct symbolism—pathologic, phallic, and erotic—and this accusation is serious for the artist who is unable to argue on the basis of stylization. … In discussion with Weston on this very point I became convinced that there is no conscious attempt to imply symbolism of any sort in his work. In deference to him as an artist I must accept his word that he is not conscious of any effort in this direction—that his photographs are entirely devoid of intentional symbolic connotations. … / … / The very complexity of the natural world obviously implies coincidence of form and function through our imagination. In certain aspects a pepper may easily suggest the curved lines of a human torso, even though the presentation of a pepper in this aspect was not intended by the artist. / … / I am satisfied that an answer to the charge of symbolism will be found in some combination of the above integration. … / It is a pleasure to observe in Weston’s work the lack of affectation in his use of simple, almost frugal, materials. His attachment to objects of nature rather than to the sophisticated subjects of modern life is in accord with his frankness and simplicity. The progress of Weston’s work to date is rapid and significant, and his development in the future promises to be an important strengthening element in the complete establishment of photography as a fine art. Finally, may I quote what Diego Rivera said as we were speaking of Edward Weston—’For me, he is a great artist.’

Weston remained unfazed by Adams’ criticism, noting in his Daybook on 1 February 1932[45]:

I have a splendid negative of the “turkish-turban” squash: it will go with my New York exhibit [Delphic Studios, 29 February–13 March 1932]. … Ansel Adams wrote an article on the S.F. show [M.H. de Young Memorial Museum, 17 November–16 December 1931]: it contains debatable parts, though on the whole intelligently considered. / … / Ansel did not care for my vegetables—least of all the halved ones. This is nothing new! I seem to be continually defending them! I can see the resemblance of some of them, especially the oft-maligned peppers, to modern sculpture, —or Negro carving—but I certainly did not make them for this reason. / …

(CCP, Sonya Noskowiak Collection/Gift of Arthur Noskowiak, 76.10.9)

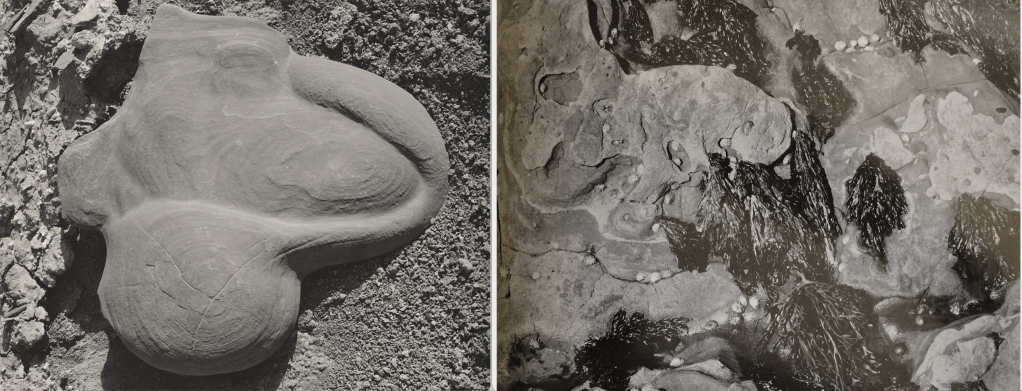

The inherent nature and forms of food remained fertile themes in Weston’s oeuvre until about 1936, when he shifted away from studio-based still lifes to expansive landscapes and other evocative outdoor subjects. Yet, echoes of these intimate works continued to be found in the closely observed, abstracted environmental studies of rocks, tide pools, sandstone concretions and other elements that peppered Weston’s work for the remainder of his career.

(Yale University Art Gallery, Gift of Charles Seymour, Jr., B.A. 1935, Ph.D. 1938; 1964.62.1)

(CCP, Edward Weston Archive, 81.278.5)

Right: Untitled [eroded rock and kelp, Point Lobos], 1941, as illustrated in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass Illustrated with Photographs by Edward Weston, published by The Limited Editions Club, 1942.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this two-part venture when we conclude with a discussion of “Edward Weston’s Campfire Cuisine.”

NOTES

1 “Ex-Rabbit,” The New Yorker 22:2, 23 February 1946, 22–23.

2 Merle Armitage, “The Photography of Edward Weston,” Touring Topics 22:6 (June 1930): Non-paginated Rotogravure section between pp. 34–35.

3 Edward Weston. The Daybooks of Edward Weston. Vol. 2, California. Edited by Nancy Newhall. Millerton, N.Y.: 1973. , 1 September 1927, p. 38; 29 October 1927, p. 40.

4 “Edward Weston—A Half Century of Photography,” Carmel Pacific Spectator-Journal 13:5, June 1956, Cover, 5–13.

5 Op. Cit. Daybooks, California, 12 November 1927, p. 41.

6 Bertha Wardell and Arts and Crafts Society, [invitation/program for] Dances With Percussion Instruments and Dances in Silence Los Angeles: 29 April 1928. (Collection of Paul M. Hertzmann, Inc.).

Weston refers to this dance program in his Daybook entry for April 17, 1928 (Aperture edition, 1990, Vol. II, California, p. 54): “B. is to dance on Olive Hill next Sunday. The program is rather well done. On the cover is reproduced my photograph of her knees which holds its own as one of my best.”

7 Op. cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California, 1 September 1927, p. 38; 29 October 1927, p. 40.

8 Ibid., 25 March 1930, p. 149.

9 Edward Weston. The Daybooks of Edward Weston. Vol. 1, Mexico. Edited by Nancy Newhall. Millerton, N.Y.: 1973. 8 December 1924, p. 107.

10 Ibid., 2 April 1924, p. 61.

11 Ibid., 4 July 1926, pp. 183–184.

12 Op. Cit. The New Yorker, 23 February 1946.

13 Edward Weston. The Daybooks of Edward Weston. Vol. 2, California. Edited by Nancy Newhall. Millerton, N.Y.: 1973. 2 October 1929, p. 134.

14 Eric Collin, “The Watch Tower: Myrto Childe, the entertaining chef at the Mona Mona, appeared at the Edward Weston masquerade…,” The Carmel Pine Cone 15:39, 27 September 1929, 10.

15 “Revelry by Night,” The Carmelite 2:33, 25 September 1929, 2.

16 Op. cit. Daybooks, vol. 2, California. 20, 26 September and 2 October 1929, pp. 133–134.

17 Louis Clyde Stoumen, “Week-end with Weston,” Photo Notes, June 1948, 11–14.

18 Tropico, The City Beautiful: Official Program And Souvenir of the Knights of Pythias Carnival. Text by G. C. Henderson and Robt. A. Oliver. Tropico, California: The Valley Press, n.d. [1915]. Thirty Weston photographs are illustrated in this booklet.

19 Op. cit., Daybooks, Mexico, 30 September 1924, pp. 92–93.

20 Op. cit., Daybooks, California, 4 April 1927, p. 13.

21 Ibid., 10 September 1927, p. 39.

22 Ibid., 6 April 1927, p. 13.

23 [Weston, Edward]. [Untitled pictorial section composed of eight Weston photographs]. The School Arts Magazine 31:10 (June 1932): 602–604. This pictorial piece is neither titled nor listed on the magazine’s “Contents” page. Eight Weston photographs are illustrated, five of which are fruit or vegetable still lifes. Although none of the photographs bear titles, each page provides a brief descriptive caption that serves to identify the images on that page. These five photographs are: Bananas, 1930? (Not in Conger); Onion Halved, 1930 (Conger 623/1930); Cabbage Leaf, 1931 (Conger 649/1931); Red Cabbage Halved, 1930 (Conger 613/1930); and Pepper No. 30, 1930 (Conger 606/1930).

24 Op. cit., Daybooks, California, 1 August 1930, p. 180.

25 Ibid., 14 November 1930, p. 195.

26 Op. cit., Daybooks, California, 23 April 1931, p. 213.

27 Ibid., 23 February 1931, p. 206

28 Ibid., 18 June 1930, p. 168.

29 Jerome Klein, Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, 28 October 1930.

A clipping of this article is located in the Edward Weston Archives at the Center for Creative Photography, Scrapbook C, page 101. Unfortunately, Weston’s clipping excludes the article’s title and the page number and I have been unable to locate a copy of the Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World for verification. Klein was an art historian, proponent of Modern art, and a critic for the New York [Evening?] Post and other publications. Perhaps the article was syndicated in the Chicago Post Magazine of the Art World.

30 Edward Weston, Edward Weston Photographer: Portraits / Prints For Collectors, Carmel, California: Edward Weston, after April 1931. Weston’s brochure quotes and cites Jerome Klein as follows: “ ‘Hard-boiled eggs and a wire slicing device—not very inspiring material, one might say—yet out of it Edward Weston has created a masterpiece.’ / JEROME KLEIN, / ‘Chicago Evening Post / Magazine of the Art World,’ / October 28, 1931.” NOTE: The date of 1931 printed in this brochure is incorrect; the article actually appeared in 1930.

31 The twenty-four still life subjects included on the 1930 Delphic Studios exhibition checklist were comprised of three shells, one eggplant, one eggs and slicer, one egg slicer, two bananas, two cabbages, two winter squash, one artichoke halved, two bones, one celery heart, and eight peppers.

32 Frances D. McMullen, “Lowly Things That Yield Strange, Stark Beauty,” The New York Times Magazine, 16 November 1930, 7, 20. Weston quotes this review in his 1931 promotional brochure; see Note 30, above.

33 Margaret Breuning, “The Art Season in Full Swing With Many Large and Small Exhibitions: Local Galleries: Edward Weston is holding…,” New York Evening Post, 25 October 1930, D-6. Weston quotes this review in his 1931 promotional brochure; see Note 30, above.

34 Merle Armitage. Fit for a King, The Merle Armitage Book of Food. Edited by Ramiel McGehee. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1939.

35 Harriet Brown Seymour, “Edward Weston, The Seer,” The Carmelite 3:38, 30 October 1930, 6.

36 Delphic Studios, “Delphic Studios Always On View…” The Art Digest 5:12, 15 March 1931, 4. This advertisement reads: “DELPHIC STUDIOS / ALWAYS ON VIEW / Paintings, Drawings, Mural Studies, / Lithographs, by / OROZCO / Photographs by EDWARD WESTON / 9 East 57th Street.” The statement “Always on View” implies that works by both Weston and Orozco were regularly exhibited and/or available for viewing at the Delphic Studios in the period around March 1931.

37 “Beauty in Vegetables,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Magazine for Women, 15 May 1932, 7. The impetus for this article may have been a second Weston exhibition at the Delphic from 29 February–13 March 1932, although only one of the photographs illustrated in the article, Cabbage Leaf, 1930, appeared in that show.

38 [Harvard Society for Contemporary Art]. Photography 1930 Harvard Society for Contemporary Art 1400 Massachusetts Ave., Cambridge, November 7 to 29. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Society for Contemporary Art, November 1930. This was the original venue for an exhibition with subsequent travel to the Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, Connecticut, [7–21] December 1930 and, possibly in revised form, Goucher College, Baltimore, Maryland, 23 February–? March 1931.

39 Typewritten letter dated 12 November 1930, to Weston from Sophia R. Ames, Secretary of The Harvard Society for Contemporary Art. (Edward Weston Archives, Center for Creative Photography, Scrapbook A, n.p.)

40 Op. Cit. Merle Armitage, Touring Topics.

41 “Die Natur schafft Bildwerke” [Nature creates sculpture], Die Dame 59:4, November 1931, 38. (Edward Weston Archive, Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona; Scrapbook A)

42 Louise Bjørner, “Naturen Som Billedhugger” [“Nature As Sculptor”], Politiken Magasinet [Copenhagen] 2:22 (5 June 1932): n.p. [14–15]. The seven Weston photographs illustrated are: Point Lobos, 1930 (Conger 630/1930); Eroded Rock No. 50, 1930 (Conger 633/1930); Cabbage Fragment (Conger 652/1931); Pepper, 1929 (Conger 562/1929); Shell and Rock Arrangement, 1931 (Conger 655/1931); Kelp, 1930 (Conger 584/1930); and Cypress, Point Lobos, 1930 (Conger 641/1930).

43 [Edward Weston], “Artichoke; Onion; Cabbage Sprout,” Coronet 1:1, November 1936, 26–28. Weston’s vegetable still life subjects appeared in the following subsequent issues of Coronet as well: December 1936 (1 illustration), February 1937 (1 illustration), April 1937 (2 illustrations), and May 1937 (1 illustration).

44 Ansel E. Adams, “Photography,” The Fortnightly 1:8, 18 December 1931, 21–22.

45 Op. Cit. Daybooks, California, 1 February 1931, p. 239.

Dear Paula:

Such wonderful writing – I am HUNGRY!

Will have to savor this in detail later today.

Miss you!

Xxx

j

LikeLike

Thanks, Jeannine. Praise from you is high praise indeed. Me? I’m about to have a banana and a peach for lunch… xox.

LikeLike