ArtSeen

Robert Motherwell Drawing: As Fast as the Mind Itself

The Elastic Hand and the Agile Mind of Robert Motherwell

On View

Menil Drawing InstituteRobert Motherwell Drawing: As Fast as the Mind Itself

November 12, 2022–March 12, 2023

Houston, Texas

“Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

“In skating over thin ice our safety is in our speed.”

Robert Motherwell Drawing: As Fast as the Mind Itself, a comprehensive survey of Motherwell’s drawings, is quite literally an eye-opening exhibition. Exquisitely curated by Edouard Kopp, chief curator at Menil Drawing Institute, this gathering of about a hundred works on paper made me think of how the artist’s great variety of touch on various kinds of paper surfaces is in some ways akin to the movements of a prodigious ice skater who takes the risk of moving across the ice with remarkable courage and agility. Just as a great skater needs a combination of fortitude and athleticism that can include jump elements, spin elements, and step sequences that require a variety of body movements, Motherwell’s remarkable drawing repertoire employs mark making that includes thick and thin lines, stains, blots, and brush strokes in endless forms and speeds of execution. All of which, we see, evolved over time, with his own invented poetic and pictorial language, which for all its variety also created a strong sense of continuity, informed by unfailing thoughtful meditation.

The works in the exhibition, which come from several public and private collections, are divided into four large rooms, each of which contains a selection that represents the artist’s practice at a different time within his prolific fifty-year career. Seeing this show, I must confess, made me rethink much of what I’ve taken for granted about Motherwell. For although my feelings about his work have always been commendatory, this exhibition was one of those rare instances where careful curation and the sheer quality of the work make you see things freshy.

The first room starts with Mexican Sketchbook (1941), which reveals the artist’s fearless entry to his experiment with Surrealist psychic automatism, leading to how—in his own interpretation of Synthetic Cubism—Surrealist form could be extended into pictorial possibilities in which emotional content were infused with formal structure. A wonderful example of this is one of the most famous among the drawings of this period, Three Figures Shot (1944). This work features three dissimilar abstract figures standing erect, covered with spattering red-ink, and embodies a kind of lyrical violence. It also shows Motherwell’s break with Surrealism’s dogmatic rigidity, by shifting to an approach that invites chance and also embraces his own deep feelings.

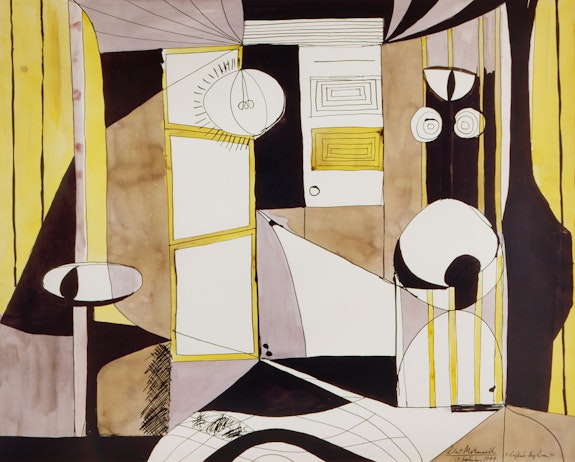

Doing so implies on occasion addressing certain formal issues that can be isolated in order to attain pictorial clarity, as seen in the rarely seen Kafka’s Big Room (1944), where elements of light versus dark, transparency versus opacity, straight lines versus curved lines, are clearly demarcated. Even more pared-down minimal means are employed in another early drawing, Untitled (1946), which features three irregular vertical columns slanting to the right, while the white one in the middle negotiates the negative spaces around it as needed for the whole picture’s architectonic stability.

Some classic collages are also included in the exhibition, such as the monumental Figure with Blots (1943) and the ecstatic Stars and Moons (1951). While the former expresses the freedom with which the artist explores the inventiveness of the medium by having painted forms intersect with drawing and collage elements, the latter injects simplicity with airiness, wit, and humor. Although Motherwell was intensely aware of the political issues around him during this period, as reflected in his sympathetic identification with both Mexico’s struggles for independence and the devastation of the Spanish Civil War, his own very intense emotionality and compassion were channeled through his personal mediation with abstraction as a symbolic action to affirm personal freedom and resist tyranny.

Having studied philosophy, Motherwell intellectually understood how to process his ideas, emotions, and the materials into his own abstraction. In other words, concepts such as human vulnerability or freedom are real but are not directly tied to any concrete physical objects or experiences. Yet objects of any value must be created from nothing, as must values themselves. These issues are apparent in the second room of the exhibition, which begins with a wonderful selection of Motherwell’s most iconic “Elegies to the Spanish Republic” series, including the very first one: Elegy to the Spanish Republic No.1 (1948). It is not merely coincidental that this series is rooted in poetry: this first “Elegy” drawing is an abstract illumination of hand-written words from a poem by Harold Rosenberg, which was intended to be published in the avant-garde periodical Possibilities. For poetry played a very important part in Motherwell’s life work. The forms of this first “Elegy” have some of the rhythmic quality of verse, evoked by the dynamic permutations of black forms versus white ground, the interactions of positive versus negative spaces, and the ways their relative scales are compressed and expanded. (The “Elegies” also call to mind the monumental intimacy of Albert Pinkham Ryder’s paintings, especially with Moonlight Marine of 1870–90, which can also be taken as metaphors for life and death, as well as a lamentation after the Spanish Civil War.) As is well known, the first painting in the “Elegies” series, At Five in the Afternoon (1948–49), took its title from a poem by Federico García Lorca, who was killed by fascists near the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. But Motherwell’s connections with poetry do not stop there. Throughout his life, his work reflects his deep and thoughtful reading of poetry, which mattered to him more than to any other American artist of his generation.

Whatever degree of existential angst Motherwell may have felt during the making of “Elegies to the Spanish Republic” images, it was expressed in restrained and magisterial geometry. Whereas with a group of works made in the summer of 1958, the reactivation of automatism seems to be completely unrestrained, in spite of the artist’s attention to keeping the purity of line intact. The contrasts within and between Motherwell’s different kinds of works, and the interactions between variations of thought process and material experimentations, are very well brought out by Kopp’s deliberate curation. At times, the installation prominently shows a single body of works on one wall, but at other times presents different bodies of works together on the same wall without following a strict chronology. We the viewers are therefore reassured to experience the multiplicity of Motherwell’s rich and complex evolution as an artist.

Motherwell’s practice of making collages, in which the edges of torn paper can be seen to constitute another form of drawing, makes a striking contrast with his series of “Elegies to the Spanish Republic.” Although both can be seen as formal inventions, Motherwell’s exploration of psychic automatism, however, underlies almost all his works, and can be thought of as a conduit for transmitting the energy of his inner emotion through the eloquence of lines. What I admire most about Motherwell’s multitudes is the autonomous space, from which the collision between writing and drawing, line and mark-making, stain and blot, and so on, occurs as testaments of his love for poetry—a form of literature that elicits a concentrated imaginative mindfulness of experience or a particular emotional response through language, from which meaning emerges with sound and rhythm.

The most generous attribution of Motherwell’s calligraphic language in forms and gestures is brilliantly installed in room three. Featuring twenty-four ink drawings from the “Lyric Suite” series, painted on special Japanese paper, on which the absorbance of the paper’s delicate and thin fiber tissue demands a decisive movement of the hand in the application of the ink, be it fast or slow, dripping or staining, brushing or pouring. A similar spontaneity runs through many other works such as Sky and Pelikan (1961), and Summertime in Italy (1960), which were done with oil paints on particular papers that allow the oil to migrate over time around the edges, creating unexpected yet expressive auras to the drawings.

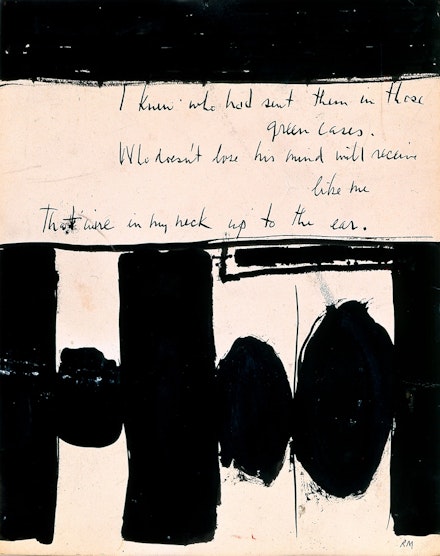

In the last room, which highlights several different kinds of works dating from 1967 to 1987, the artist’s own human condition in confronting his unknown space intensifies. Motherwell’s restless nature, permeated by his intense search for reconciliation of the ongoing predicament between mind and body, intellect and emotion, fullness and emptiness, becomes vividly apparent. Whatever else may within the tensions between pairs of opposites, which tremble with anxiety, his fearless inquiry into the nature of art, and the inner freedom it provides, seems to evoke within us, the viewers, the potential to see our own vulnerabilities as endless sources of vital energy—ways of being able to be free from something or of becoming free to be something else. Here Kopp’s thoughtful curatorial juxtapositions correlate to Motherwell’s own Sturm und Drang. For example, on one wall, we see a group of works from the “Rimbaud” series, populated by the density of black forms as the artist’s response to the French poet’s powerful desire to break free from life’s stringent brutality of weightiness. While a vitrine includes several works “from the Joyce Sketchbook” (1985) that thrive upon the lightness of drunken lines in association with Joyce’s own masterful propagation of automatism. The same can be said of the two “Black on White” works in relation to the four examples of the “Open Study” series. Likewise, the inclusion of the three collages, Scarlet with Gauloises No. 8 (1972), Black Refracts Heat (1974), The Red and Black No. 51 (1987) are examples par excellence of Motherwell’s endless way of elevating collage as a legitimate art form that has its own weather and temperature.

Lastly, what added to my already rapturous reception to this remarkable survey, came at the tail end, while looking at the three works on the central wall. On the left is Drunk with Turpentine No. 40 (1979), which refers to the artist’s power of transference in how he reinterpreted Zen master Sengai’s most famous sumi-e painting of a square, a triangle, and a circle (referred to in English as The Universe [Edo period]). While Sengai painted in a horizontal formation, Motherwell turns it to a vertical format with the same progression of order, yet the images are held captive within a window-like structure; and I notice how the square at the bottom has become a solid black rectangle, overlapping the right edge of the structure, implying a desire to break free from such confinement. Just to the right of this, what remains in Drunk with Turpentine No. 2 (Stephen's Gate) (1979) is the triangle in its frantic countenance, also trying to break free from its surrounding structure. Finally, in the middle picture, simply titled Drunk with Turpentine (1979), one incomplete triangle turns into its double image, from which the bottom line becomes the base for the sculpted letter M, which can be read as the first letter of the artist’s last name.

I came away thinking of how Motherwell managed to activate John Keats’s “negative capability,” while being perhaps among the very few artists of any generation who has successfully brought the philosophy of Western and Eastern traditions into one resonant synthesis. His is a profound contribution indeed.

P.S. The exhibition is accompanied by an excellent, fully illustrated catalogue, authored by Edouard Kopp. In addition, a comprehensive publication, Robert Motherwell Drawings, a catalogue raisonné by Katy Rogers, documenting Motherwell’s 1,413 drawings, was recently published by Yale University Press. Thoroughly researched, wonderfully written, and beautifully produced, this highly anticipated catalogue raisonné will serve as the definitive resource on Motherwell’s drawings for years to come.