Exhibition dates: 7th March – 21st June 2015

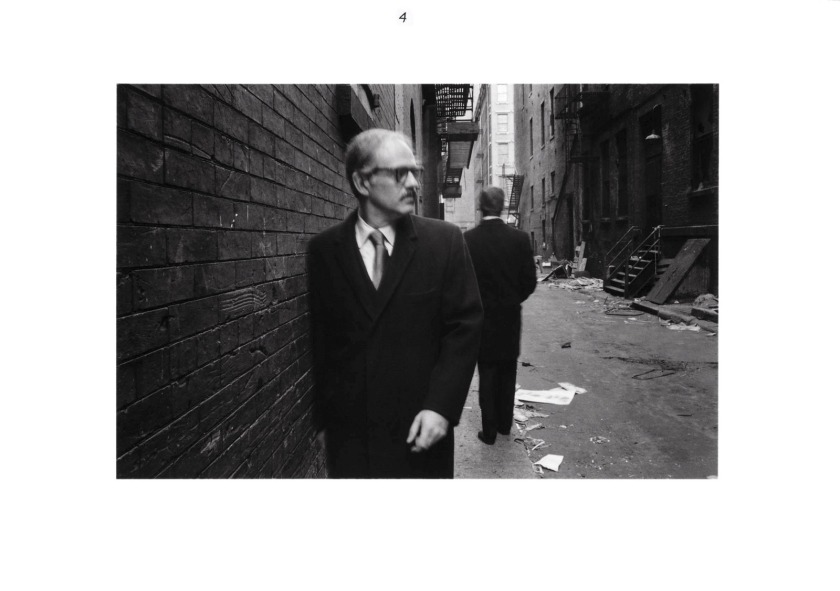

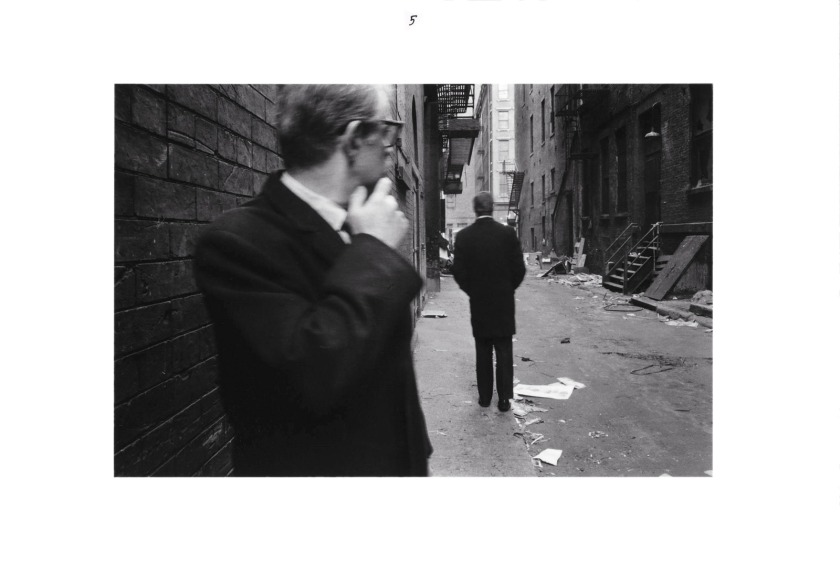

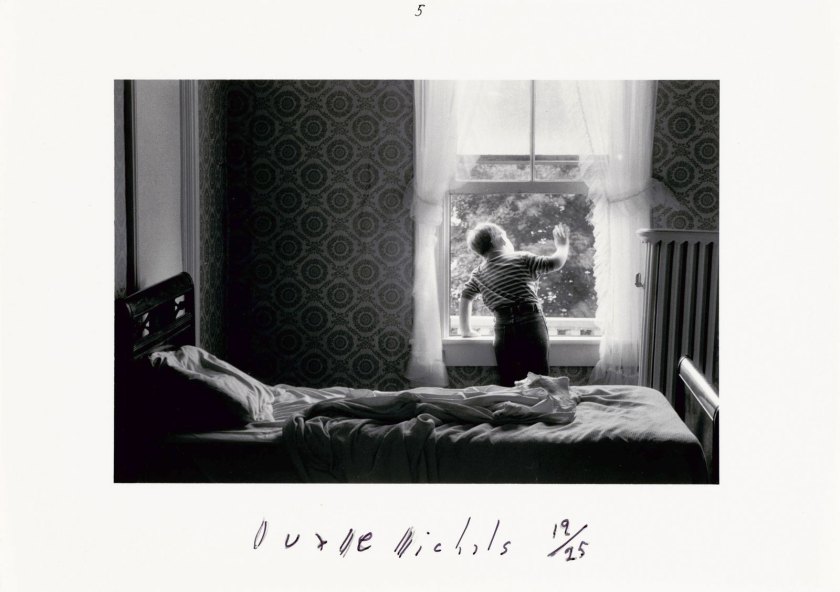

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

From the series I Remember Pittsburgh

1982

Nine gelatin silver prints

Greenwald Photograph Fund and Fine Arts Discretionary Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

I couldn’t resist. Another posting on the work of this extraordinary artist. I particularly like The Bewitched Bee (1986) and Who is Sidney Sherman?, replete with blond wig and fag hanging out of the mouth accompanied by very funny and perceptive text.

There is also a very interesting piece of writing on life and photography included in the posting, Real Dreams, from 1976.

Marcus

.

Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I’m not interested in what something looks like, I want to know what it feels like.”

.

Duane Michals

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Bewitched Bee

1986

Thirteen gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text

5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.8 cm)

Michals uses photography to spin what amount to Ovidian legends, as in The Bewitched Bee, a sequence of thirteen images in which a young man stung by a bee grows antlers, wanders through the woods, and finally drowns in a sea of leaves.

The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) presents Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals, the first major U.S. retrospective of the artist’s work in 20 years. Through image sequences, multiple exposures and the overlay of handwritten messages and pigment, Duane Michals (b. 1932) pioneered distinctly new ways of creating and considering photographs. The last half-century of this artist’s prolific, trailblazing career is explored in a carefully selected presentation of more than 65 works. Organised by the Carnegie Museum of Art, Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals is on view at PEM from March 7 through June 21, 2015.

Michals’ career has been fuelled by his enduring curiosity about the human experience and has been defined by its continual creative exploration and reinvention. A self-taught practitioner, he emerged on the photographic scene in the 1960s, at a time when Ansel Adams’ austere mountain ranges and Henri Cartier-Bresson’s iconic street scenes ruled the day. Rather than journey outward to depict nature or patiently wait to capture a decisive moment, Michals sought a new method of expression for his psychological and imaginative vision. He worked with friends and acquaintances to stage sequences of photographs that sought to express things that cannot be seen directly, such as metaphysical reflections on the passage from life to death. Later, he added handwritten text to the images’ margins, further challenging the prevailing sanctity of the single pure photograph.

“For Michals, the need to authentically express himself trumped any interest in being accepted into the mainstream art world. His work charts fresh territory, creatively mixing philosophical rigour, surreal witticism and childlike playfulness with an unabashed sentimentality and nostalgic longing,” says Trevor Smith, PEM’s Curator of the Present Tense. “In Michals’ photographs we encounter an uncommon vulnerability as well as a resolute search for meaning and human connection.”

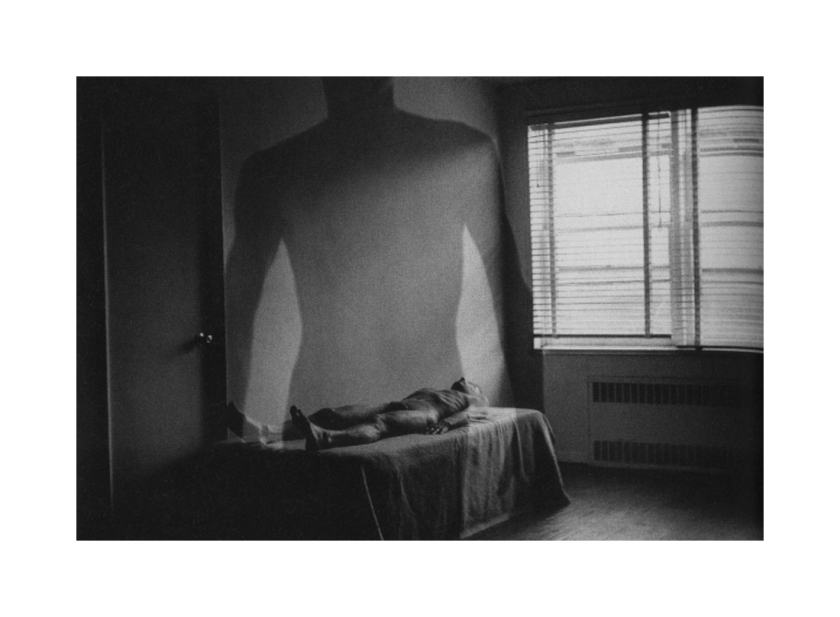

Raised in a steelworking family outside of Pittsburgh, Michals has explored familial and personal identity as a recurring theme. In a rarely exhibited 30-photograph sequence titled The House I Once Called Home (2003), the artist explores the abandoned three-story brick house where he spent his childhood. Each image is paired with poetic verse of remembrance and reflection to create an intimate photographic memoir and metaphysical scrapbook. Recent photographs are superimposed on historic images as the series toggles through time, space and memory. The home’s current dilapidated state contrasts with reveries of a formerly bustling family home and a rumination on the passage of time and the inevitable succession of generations.

Michals’ lifelong adventure with photography began on a trip to Russia in 1958. Borrowing a camera from a friend, he discovered a way to interact with people and tell stories. Shortly thereafter, Michals moved to New York City where he supported himself through work as a commercial photographer for Vogue, Esquire and Life magazines and took portraits of notable artists including Meryl Streep, Sting and Willem de Kooning. In the 1960s, Michals began his earliest experimental narrative sequences that were exhibited in 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The curator of the show, William Burback, noted that “the mysterious situations Michals invents are posed and theatrical. Yet, they are so common to the urban condition that we have the illusion of remembering scenes and events experienced for the first time.” Later he began adding text to his photographs such as This Photograph Is My Proof (from 1974), which allowed him to tell stories and address feelings that could not be fully explored by photography alone.

Rather than take cues from his photographic contemporaries, Michals considers surrealist painters such as René Magritte, Balthus and Giorgio de Chirico to be his artistic heroes. Scratching out universal truths from the mystery of human experience, Michals has explained that his works are, “about questions, they are not about answers.” Over the decades, he has been at the forefront of exploring sexual identity and the struggles for gay rights. In his 1976 work, The Unfortunate Man, a model arches his back in anguish while the accompanying text reads: The unfortunate man could not touch the one he loved. It was declared illegal by the law. Slowly his fingers became his toes and his hands gradually became feet. He wore shoes on his hands to disguise his pain. It never occurs to him to break the law.

One of the constants of Michals’ career – from his classic narrative sequences to his more recent series of hand-painted tintypes – has been his preference for intimately scaled images with tactile surface treatments. These works, with their universal themes of memory, dreams, desire and mortality, draw the viewer closer and insist on their full engagement at an emotional level. Commenting on why Michals includes handwritten text on his images, he has said: “I love the intimacy of the hand. It’s like listening to someone speaking.”

Press release from the PEM website

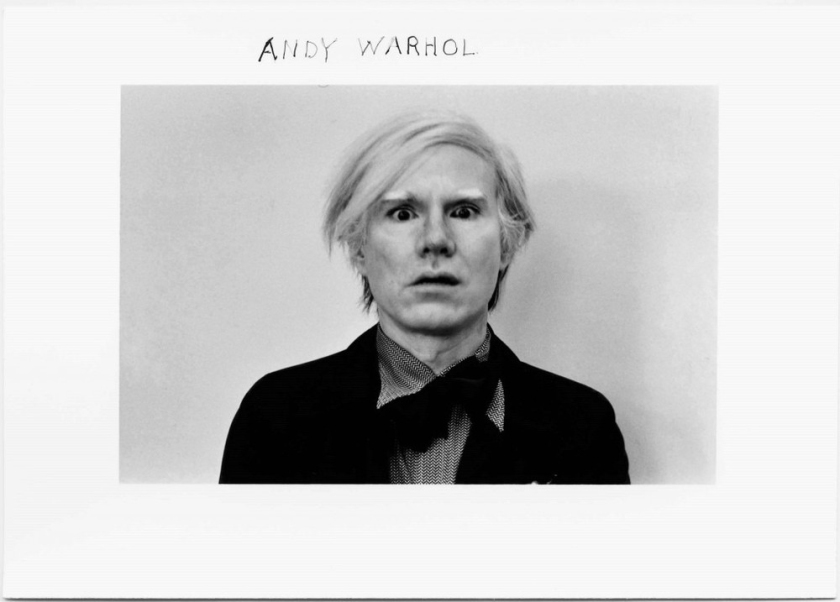

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Andy Warhol

1972

© Duane Michals; The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

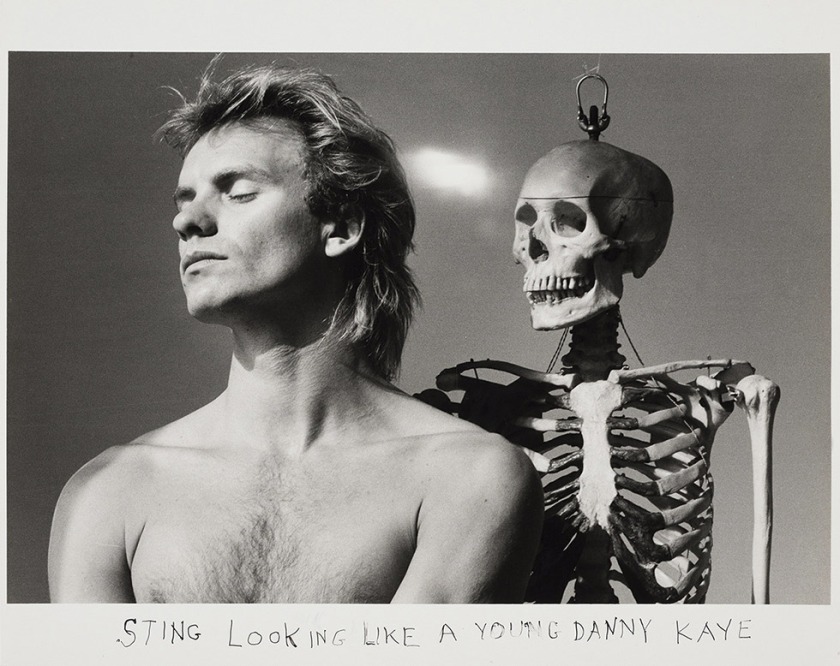

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Sting

1982

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery and the artist

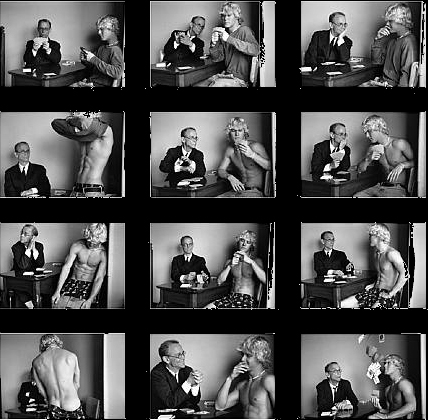

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Great Photographers of My Time #2

1991

Gelatin silver print

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

The Unfortunate Man

1976

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

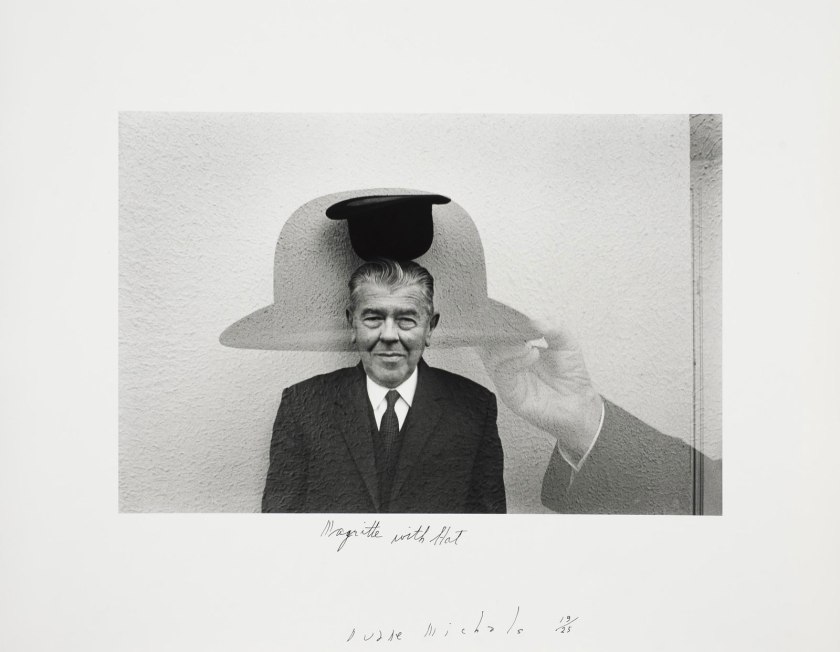

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Magritte at His Easel

1965

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Georgette and Rene Magritte

1965

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Self Portrait as a Devil on the Occasion of My Fortieth Birthday

1972

© Duane Michals

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Primavera

1984

© Duane Michals

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh.

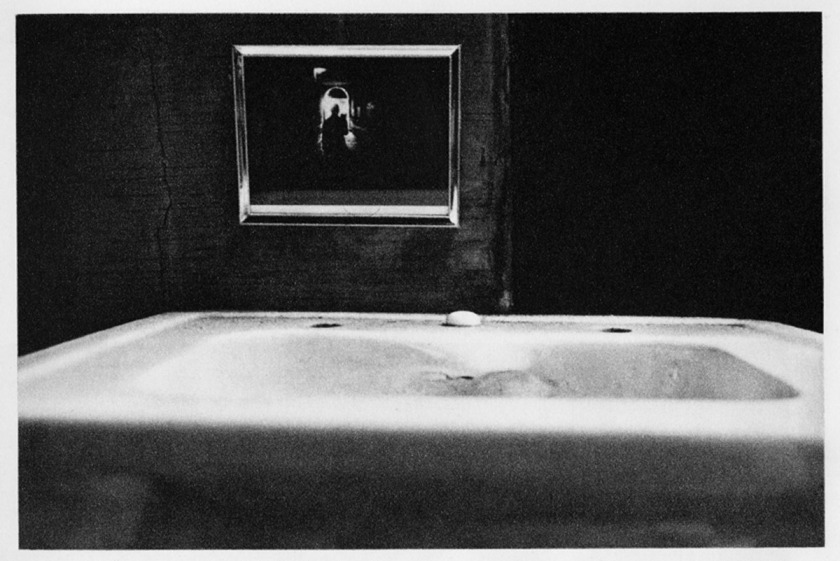

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

From the series The House I Once Called Home

2002

Thirty gelatin silver prints with hand-applied text

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Randy Duchaine

Duane Michals, portrait with red nose

2015

Photo courtesy of Randy Duchaine

Real Dreams

by Duane Michals

Nothing is what I once thought it was. You are not what you think you are. You are nothing you can imagine.

I am a short story writer. Most often photographers are reporters. I am an orange.

They are apples.

One of the biggest cliches in photography is to say that he is a personal photographer.

We must touch each other to stay human. Touch is the only thing that can save us.

I use photography to help me explain my experiences to myself.

Some photographers literally shoot everything that moves, hoping somehow, in all that confusion to discover a photograph. The difference between the artist and the amateur is a sense of control. There is a great power in knowing exactly what you are doing, even when you don’t know.

We are all stars. We just don’t know it.

I practice being Duane Michals everyday – that’s all I know.

Most portraits are lies. People are rarely what they appear to be, especially in front of a camera. You might know me your entire lifetime and never reveal yourself to me. To interpret wrinkles as character is insult not insight.

Was there ever a 1956? What did I do in June 1971? What happened in 1956? I think that there was 1932.

The history of photography has not been written. You will write it. No one has photographed a nude until you have. No one has photographed a sequence or green pepper till you have. Nothing has been done until you do it.

There are no answers anymore.

Get (Edward) Weston off your back, forget (Diane) Arbus, (Robert) Frank, (Ansel) Adams, (Clarence) White, don’t look at photographs. Kill the Buddha.

I am my own hero.

Photography books have titles like “The Photographer’s Eye” or “The Vision of So and So” or “Seeing Photographers” – as if photographers didn’t have minds, only eyes.

Everything is going; yes, even you must go. Right now you are going. Right now!

I find myself talking to photographs. I see a photograph of a women and I ask, “Is that all you’re going to tell me?” I can see the long hair and costume. Is she a witch, a mother, kind, consuming? Does she believe anything? I want more.

As I write this, at this moment, thousands of people are dying, thousands are being born, the earth is totally alive with Spring lust, stars are exploding – my God!

It is the great unknowing that we all live in, that we call life, that I find overwhelming. And I think that I will never know, never.

I am the limits of my work. You are the limits of yours. This is a journey. We do not live here. When I say “I,” I mean We.

As soon as I say “now,” it becomes “then.”

It is very easy for photographers to fake. Just go out and photograph twenty Pizza Huts.

That’s all there is, change.

Some influences open doors and liberate, other influences close doors and suffocate.

Photography, particularly, is suffocating.

I believe in the imagination. What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see.

Photographers tell me what I already know. The recognition of the beautiful, bizarre, or boring (the three photographic B’s) is not the problem. You would have to be a refrigerator not to be moved by the beauty of Yosemite. The problem is to deal with one’s total experience, emotionally as well as visually. Photographers should tell me what I don’t know.

I find the limitations of still photography enormous. One must redefine photography, as it is necessary to redefine one’s life in terms of one’s own needs. Each generation should redefine the language and all its experiences in terms of itself.

The key word is expression – not photography, not painting, not writing. You are the event, not your parents, friends, gurus. Only you can teach yourself.

Everything we experience is in our mind. It is all mind. What you are reading now, hearing now, feeling now…

We’re all afraid of dying. We’ve already died. Look at your high school graduation picture, she’s dead! Just now, you died.

It is essential for me to be silly. If one is serious, one must also be foolish, to survive.

Trying to communicate one true feeling on my own terms is a constant problem.

I am compulsive in my preoccupation with death. In some way I am preparing myself for my own death. Yet if someone would put a gun to my stomach, I would pee my pants. All my metaphysical speculations would get wet.

When you look at my photographs, you are looking at my thoughts.

I am very attracted to the person of Stefan Mihal. He is the man I never became. We are complete opposites, although we were born at the same moment. If we should meet, we would explode. We are like matter and anti-matter. He is my shadow. I saved myself from him.

I only photograph what I know about, my life, I do not presume to know who blacks are or what they feel or bored suburban families or transvestites. And I never believe photographs of them staring into a camera.

I take nothing for granted. I can count on nothing. I am not sure where I once was certain. I don’t know what will be left by the time I’m fifty. That’s ok.

The sight of these words on a page pleases me. It’s like some sort of trail I’ve left behind, clues, strange marks made, that prove I was once here.

When I was about 9 ( the year my brother Tim was born), I would sit on the edge of my bed and be very still, long after the family had gone to sleep. I would try to find the “I” of “me.” I thought that if I would be very quiet, I might find that place inside that was “I.” I am still looking.

We are all a mental construction. Change our chemistry, our point of reference and reality changes.

I am a professional photographer and a spiritual dilettante: I would prefer to be a professional mystic and a dilettante photographer.

I remember the first time I sensed being lonely. I was about five at the time, living with my grandmother, and my best friend Art went away with his family. The afternoon loomed long and empty. I missed someone, I was empty. There was a lacking.

Only I am my enemy. My fear can stop me.

Never try to be an artist. Just do your work and if the work is true, it will become art.

“We must pay attention so as not to be deceived by the familiar.”

Things are what we will them to become.

It is important to stay vulnerable. To permit pain, to make mistakes, not to be intimidated by touching. Mistakes are very important, if we’re alert.

None of my photographs would have existed without my inventing them. These are not accidental encounters, witnessed on the street. I am responsible whether (Henri Cartier-) Bresson was there or not, those people would have had their picnic along the Seine. They were historical events.

There is not one photography. There is no photography. The only value judgment is the work itself. Does it move, touch, fill me?

Any one who defines photography frightens me. They are photo-fascists, the limiters.

They know! We must struggle to free ourselves constantly, not only from ourselves but especially from those who know.

It seems I am waiting for something to happen: and when it does, it will be difficult for me to imagine that I had ever been the person who is writing this. I will be someone else.

I am not interested in the perfect print. I am interested in a perfect idea. Perfect ideas survive bad prints and cheap reproductions. They can change our lives.

(If Duane wants to take pictures, he should do a study of laborers and farm workers and unwed mothers and make some social changes. Do something else – something noble. That’s what I’d do. – Stefan Mihal)

We have a way of making the most extraordinary experiences ordinary. We actually work at destroying miracles.

The best artists give themselves in their work. (Rene) Magritte was a gift, (Eugene) Atget, (Thomas) Eakins, (Odilon) Redon, (Bill) Brandt, (August) Sander(s), Balthus, (Giorgio) De Chirico, (Walt) Whitman, Cavafy. That’s all that there is to give. I am my gift to you, and you are your gift to me.

Most photographers photograph other people’s lives, seldom their own.

We must free ourselves to become what we are.

Photography describes to well.

Our parents protect us from death. But when they die, there is no one to stand between us and death.

I once thought that time was horizontal, and if I looked straight ahead, I could see next Thursday. Now I think it is vertical and diagonal and perpendicular. It’s all very confusing.

People believe in the reality of photographs, but not in the reality of paintings. That gives photographers an enormous advantage. Unfortunately, photographers also believe in the reality of photographs.

The most important sentences usually contain two words: I want, I love, I’m sorry, please forgive, please touch, I need, I care, thank you.

Everything is subject for photography, especially the difficult things of our lives: anxiety, childhood hurts, lust, nightmares. The things that cannot be seen are the most significant. They cannot be photographed, only suggested.

I would like to talk to William Blake and Thomas Eakins.

Duane Michals June 20, 1976 September 1, 1976

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Madame Schrödinger’s Cat

1998

From the series Quantum

© Duane Michals

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Paradise Regained

1968

Courtesy of the artis

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Carnegie Museum of Art

“Everything I did grew out of my frustration with the medium, the silence of the still picture,” he says, so he found the “wiggle room.” With sequences, he could add drama before and after the decisive moment. Having his subjects move created ethereal images and an awareness of time’s passage. Layering negatives challenged preconceptions.

Language, Michals says, has always been associated with photographs. A newspaper caption might tell you that 20 inches of snow fell on Boston or Vladimir Putin arrived by plane at the Olympics. “I write about what cannot be seen,” he says. “My text picks up where the photograph fails. This Photograph is my Proof, a “nice picture” of his cousin and new bride at Michals’ grandmother’s house, is metaphorically “out of focus” until Michals adds the text.

Michals uses a pen nib and ink to enhance his visual stories, writing in cursive or all capitals depending on his mood. “I like the handwriting, the texture.” He also collects original manuscripts. He describes himself as an intimist, a lover of diaries, books (he has three libraries at home in New York City), small pictures and intimacy. “My photographs whisper into the viewers’ eyes rather than shout. They say, ‘Come closer. I’ll tell you a secret.'”

Michals says he’s taken many professional risks, especially when presenting issues born of the gay community like isolation and illegal behaviour. “Remember, 20 or 30 years ago, marriage wasn’t even on the table,” he says. (Michals and Fred Gorrée, his partner of nearly 56 years, married in 2011, just days after same-sex marriage was legalised in New York.)

Unlike Robert Mapplethorpe, whom he says is more hardcore, Michals tends toward sentimentality and the legitimacy of the love between people of the same gender. “I’m not a typical gay person any more than I’m a typical person or photographer.”

That disdain for following established paths might explain why Ansel Adams and Henri Cartier-Bresson are not among his heroes. “My sources for inspiration were anybody who contradicted my mind and opened my imagination,” Michals says, like Lewis Carroll, Magritte, Joseph Cornell and surrealists in general. “Ansel Adams did not open my imagination. He dealt with Yosemite and sunsets. I was interested in metaphysical ideas, what happens when you die.”

Extract from Lisa Kosan. “Meet Duane Michals,”on the PEM website 2nd March 2015 [Online] Cited 08/06/2015. No longer available online.

Duane Michals (American, b. 1932)

Who is Sidney Sherman?

2000

© Duane Michals

The Henry L. Hillman Fund

Courtesy of Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Peabody Essex Museum

East India Square

161 Essex Street

Salem, MA 01970-3783 USA

Phone: 978-745-9500, 866-745-1876

Opening hours:

Open Thursday – Monday, 10am – 5pm

Closed Tuesdays and Wednesdays

You must be logged in to post a comment.