Exhibition dates: 24th August – 4th November 2012

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Fireplace, Hôtel Matignon, former Austrian embassy, 57 rue de Varenne, 7th arrodissement

1905

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

“… I have assembled photographic glass negatives… in all the old streets of Old Paris, artistic documents showing the beautiful civil architecture from the 16th to the 19th century. The old mansions, historic or interesting houses, beautiful façades, lovely doors, beautiful panelling, door knockers, old fountains, stylish staircases (wrought iron and wood) and interiors of all the churches in Paris… This enormous documentary and artistic collection is now finished. I can say that I possess the whole of Old Paris.”

.

Eugène Atget 1920

“The first time I saw photographs by Eugène Atget was in 1925 in the studio of Man Ray in Paris. Their impact was immediate and tremendous. There was a sudden flash of recognition – the shock of realism unadorned. The subjects were not sensational, but nevertheless shocking in their very familiarity. The real world, seen with wonderment and surprise, was mirrored in each print.”

.

Berenice Abbott 1964

Spaces That Matter…

[In revelatio, in revelation] the photographers trained eye is perhaps more of a hindrance than may at first be thought. The photographer may struggle with, “a sense of intense inevitability, insofar as this kind of image seems to be one that the photographer ‘could not not photograph’.”9 Awareness may become a double bind for the photographer. It may force the photographer to photograph because he can do nothing else, because he is aware of the presence of ‘punctum’ within a space, even an empty ‘poetic space’, but this awareness may then blind him, may ossify the condition of revealing through his directed gaze, unless he is very attentive and drops, as Harding says, “memory and imagination and desire, and just take what’s given.”10 The object, as Baudrillard notes,”isolates itself and creates a sense of emptiness … and then it irradiates this emptiness,”11 but this irradiation of emptiness does require an awareness of it in order to stabilise the transgressive fluctuations of the ecstasy of photography (which are necessarily fluid), through the making of an image that, as Baudrillard notes, “may well retrieve and immobilise subjective and objective punctum from their ‘thunderous surroundings’.”12 Knowledge of awareness is a key to this immobilisation and image making. The philosopher Krishnamurti has interesting things to say about this process, and I think it is worth quoting him extensively here:

“Now with that same attention I’m going to see that when you flatter me, or insult me, there is no image, because I’m tremendously attentive … I listen because the mind wants to find out if it is creating an image out of every word, out of every contact. I’m tremendously awake, therefore I find in myself a person who is inattentive, asleep, dull, who makes images and gets hurt – not an intelligent man. Have you understood it at least verbally? Now apply it. Then you are sensitive to every occasion, it brings its own right action. And if anybody says something to you, you are tremendously attentive, not to any prejudices, but you are attentive to your conditioning. Therefore you have established a relationship with him, which is entirely different from his relationship with you. Because if he is prejudiced, you are not; if he is unaware, you are aware. Therefore you will never create an image about him. You see the difference?”13

.

Now apply this attention to the awareness of the photographer. If he does not create images that are prejudice, could this not stop a photographer ‘not not’ photographing because he sees spaces with clarity, not as acts of performativity, spaces of ritualised production overlaid with memory, imagination, desire, and nostalgia?

Here an examination of the work of two photographers is instructive. The first, the early 20th century Parisian photographer Eugène Atget, brings to his empty street and parkscapes visions that elude the senses, visions that slip between dreaming and waking, between conscious and subconscious realms. These are not utopian spaces, not felicitous spaces that may be grasped and defined with the nostalgic fixity of spaces we love,14 but spaces of love that cannot be enclosed because Atget made no image of them.

I believe Atget moved his photographs onto a different spatio-temporal plane by not being aware of making images, aware-less-ness, dropping away the appendages of image making (technique, reality, artifice, reportage) by instinctively placing the camera where he wanted it, thus creating a unique artistic language. His images become a blend of the space of intimacy and world-space as he strains toward, “communion with the universe, in a word, space, the invisible space that man can live in nevertheless, and which surrounds him with countless presences.”15 These are not just ‘localised poetics’16 nor a memento of the absent, but the pre-essence of an intimate world space re-inscribed through the vision (the transgressive glance not the steadfast gaze) of the photographer. Atget is not just absent or present, here or there,17 but neither here nor there. His images reverberate (retentir), in Minkowski’s sense of the word, with an essence of life that flows onward in terms of time and space independent of their causality.18”

.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Excerpt from the paper Spaces That Matter: Awareness and Entropia in the Imaging of Place (2002). Read the full paper…

Endnotes

9. Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. (trans. Richard Howard). New York: Hill and Wang, 1981, p. 47, quoted in Zurbrugg, Nicholas. “‘Apocalyptic’? ‘Negative’? ‘Pessimistic’?: Baudrillard, Virilio, and techno-culture,” in Koop, Stuart (ed.,). Photography Post Photography. Melbourne: Centre for Contemporary Photography, 1995, p. 79.

10. See Endnote 2. I believe that this form of attentiveness to present experience is not the same as Featherstone’s fragmentation of time into affect-charged experiences of the presentness of the world in postmodern culture. “Postmodern everyday culture is … a culture of stylistic diversity and heterogeneity (comprising different parts or qualities), of an overload of imagery and simulations which lead to a loss of the referent or sense of reality. The subsequent fragmentation of time into a series of presents through a lack of capacity to chain signs and images into narrative sequences leads to a schizophrenic emphasis on vivid, immediate, isolated, affect-charged experiences of the presentness of the world – of intensities.”

Featherstone, Mike. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. London: Sage Publications, 1991, p. 124.

11. Baudrillard, Jean. The Transparency of Evil. (trans. James Benedict). London: Verso, 1993, quoted in Zurbrugg, Nicholas. “‘Apocalyptic’? ‘Negative’? ‘Pessimistic’?: Baudrillard, Virilio, and techno-culture,” in Koop, Stuart (ed.,). Photography Post Photography. Melbourne: Centre for Contemporary Photography, 1995, p. 80.

12. Baudrillard, Jean. The Art of Disappearance. (trans. Nicholas Zurbrugg). Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, 1994, p.9, quoted in Zurbrugg, Nicholas. “‘Apocalyptic’? ‘Negative’? ‘Pessimistic’?: Baudrillard, Virilio, and techno-culture,” in Koop, Stuart (ed.,). Photography Post Photography. Melbourne: Centre for Contemporary Photography, 1995, p. 83.

13. Krishnamurti. Beginnings of Learning. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1978, pp. 130-131.

14. Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (trans Maria Jolas). Boston: Beacon Press, 1994, p. xxxv.

15. Ibid., p. 203.

16. Palmer, Daniel. “Between Place and Non-Place: The Poetics of Empty Space,” in Palmer, Daniel (ed.,). Photofile Issue 62 (‘Fresh’). Sydney: Australian Centre for Photography, April 2001, p. 47.

17. Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (trans Maria Jolas). Boston: Beacon Press, 1994, p. 212.

18. See the editor’s note by Gilson, Etienne (ed.,) in Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. (trans Maria Jolas). Boston: Beacon Press, 1994, p. xvi.

.

Many thankx to the Art Gallery of New South Wales for allowing me to publish the photographs in this posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Boulevard de Strasbourg

1912

Albumen photograph

George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Cabaret au Tambour, 62 quai de la Tournelle, 5th arrodissement

1908

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Street vendor, place Saint-Médard, 5th arrondissement

September 1898

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

‘Spring’, by the sculptor François Barois, jardin des Tuileries, 1st arrondissement

1907

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

The first comprehensive exhibition in Australia of Eugène Atget’s (1857-1927) work will showcase over 200 photographs primarily from the more than 4000 strong collection of Musée Carnavalet, Paris with the important inclusion of Atget’s work, as compiled by Man Ray, from the collection of George Eastman House, Rochester, USA.

Atget was considered a commercial photographer who sold what he called ‘documents for artists’, ie. photographs of landscapes, close-up shots, genre scenes and other details that painters could use as reference. As soon as Atget turned his attention to photographing the streets of Paris, his work attracted the attention of leading institutions such as Musée Carnavalet and the Bibliothèque Nationale which became his principal clients. It is in these photographs of Paris that we find the best of Atget, the artist who shows us a city remote from the clichés of the Belle Époque. Atget’s images of ‘old Paris’ depict areas that had not been touched by Baron Haussmann’s 19th century modernisation program of the city. We see empty streets and buildings, details that usually pass unnoticed, all presented as rigorous, original compositions that offer a mysterious group portrait of the city.

The exhibition is organised into 11 sections that correspond to the thematic groupings used by Atget himself. They are: small trades, Parisian types and shops 1898-1922; the streets of Paris 1898-1913; ornaments 1900-1921; interiors 1901-1910; vehicles 1903-1910; gardens 1898-1914; the Seine 1900-1923; the streets of Paris 1921-1924; and outside the city centre 1899-1913.

The equipment and techniques deployed by Atget link him to 19th-century photography. He had an 18 x 24cm wooden, bellows camera which was heavy and had to be supported on a tripod. The use of glass plates allowed Atget to capture every tiny detail with great precision. Also traditional was his printing method, usually on albumen paper made light-sensitive with silver nitrate, exposed under natural light and subsequently gold-tinted. Atget’s vision of photography was, however, an astonishingly modern one. The photographs selected by Man Ray, who met Atget in the 1920s, indicate the immediate interest that the work aroused among the Surrealists because of the composition, ghosting, reflections, and its very mundanity. The first to appreciate his talents and importance as an artist were the photographer Berenice Abbott and Man Ray himself, both of whom lobbied to preserve Atget’s photographs.

As a result, he inspired artists and photographers such as Brassaï, the Surrealists, Walker Evans and Bernd & Hilla Becher amongst many others, and he can also be considered a starting-point for 20th-century documentary photography.

Press release from the AGNSW website

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

The former Collège de Chanac, 12 rue de Bièvre, 5th arrondissement

August 1900

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Rue de l’Hôtel de Ville

1921

Gelatin silver photograph

22.8 x 17.7cm

Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales

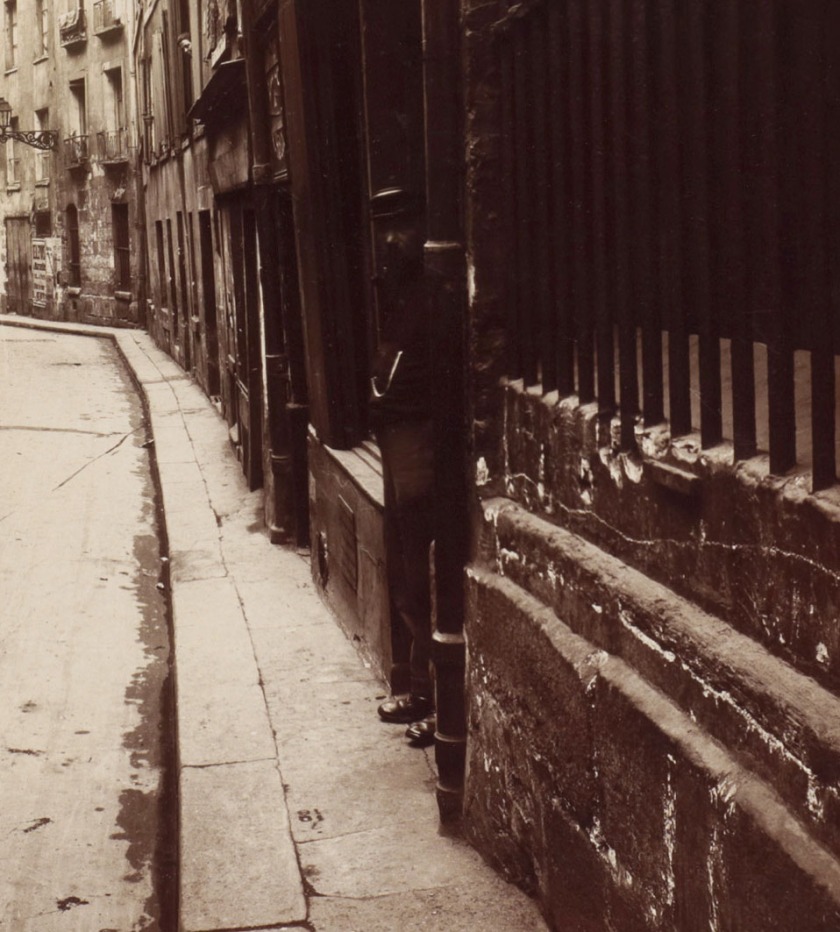

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Rue de l’Hôtel de Ville (detail)

1921

Gelatin silver photograph

22.8 x 17.7cm

Collection Art Gallery of New South Wales

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Rue Hautefeuille, 6th arrondissement

1898

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

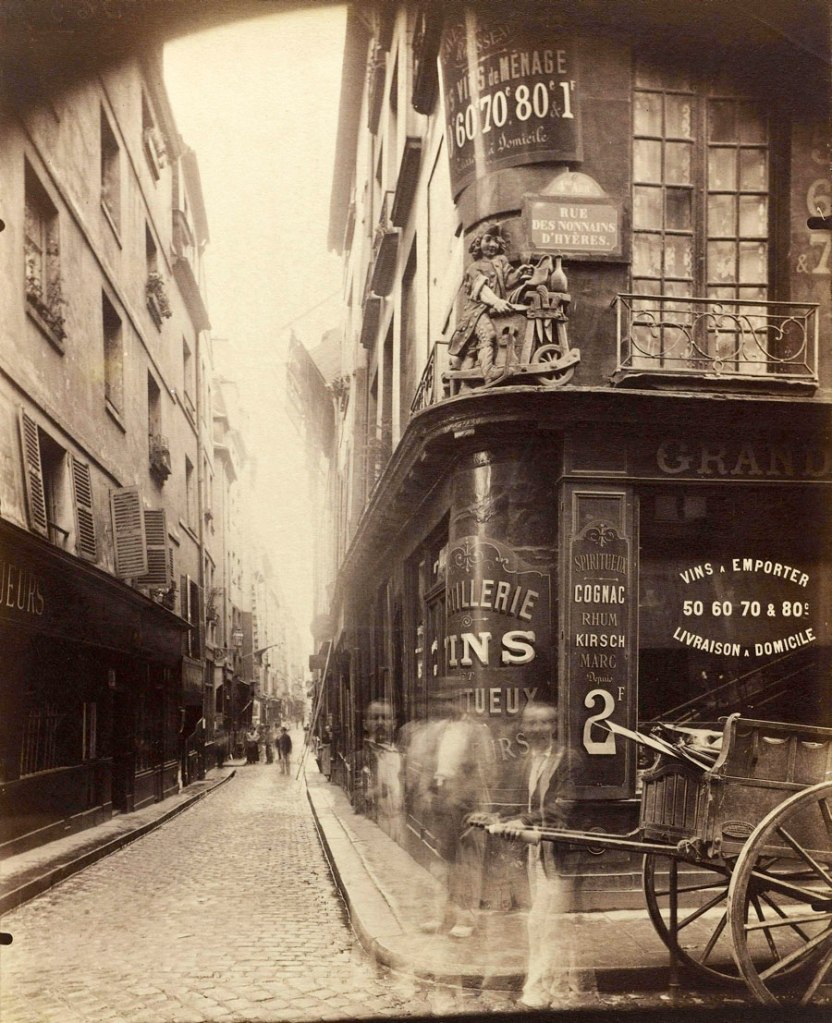

Eugène Atget (French, 1857-1927)

Shop sign, au Rémouleur on the corner of the rue des Nonnains-d’Hyères and rue de l’Hôtel-de-Ville, 4th arrondissement

July 1899

Albumen photograph

© Musée Carnavalet, Paris / Roger-Viollet / TopFoto

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

One thought on “Exhibition: ‘Eugène Atget: Old Paris’ at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney”

Comments are closed.