“If I give someone a horsetail he will have no difficulty making

a photographic enlargement of it – anyone can do that.

But to observe it, to notice and discover old forms, is something only few are capable of.“

Karl Blossfeldt

This was an OCA study visit and with two tutors, Robert Enoch and Rob Broomfield on hand, we were able to enjoy an informative view of the exhibition; it seemed the discussion never stopped and climaxed with a group discussion around the table in the Whitechapel Gallery cafe afterwards.

I found myself running a few minutes late but as I left the station a call from behind came from fellow student Brian who I had not seen for sometime; it seems his venture into wedding photography has not lead him to quit the OCA. Other familiar faces greeted me on arrival as the group waited outside. Of these, one was Robert Enoch who tutored me through a couple of Level 1 modules.

This visit interested me because it was about an early form of nature photography. Nature photography does not seem to get a lot of critical appreciation although it is a very popular form of photography often featuring in the media. Someone who has written about it for The Guardian is Parvati Nair

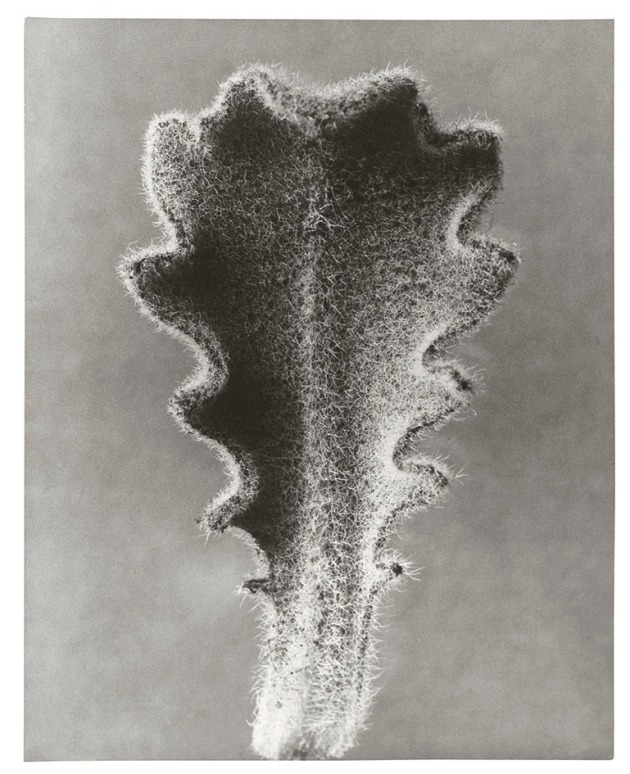

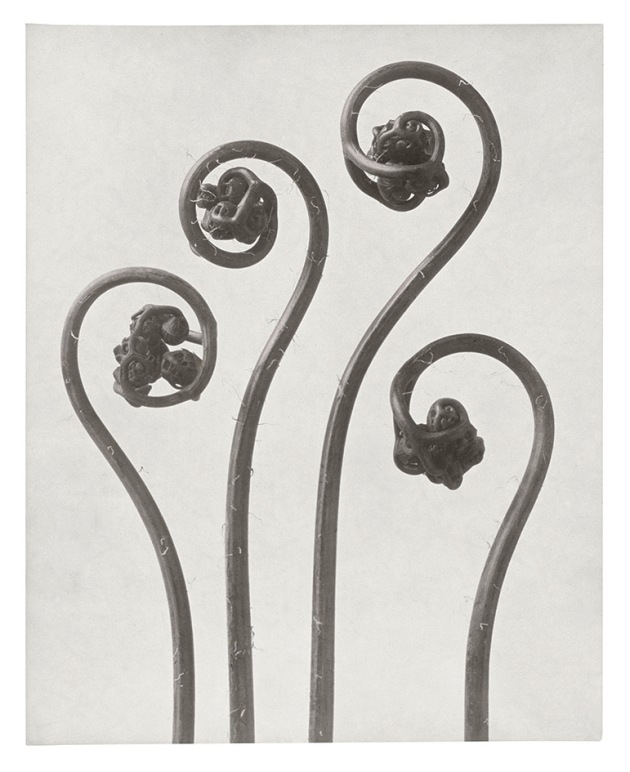

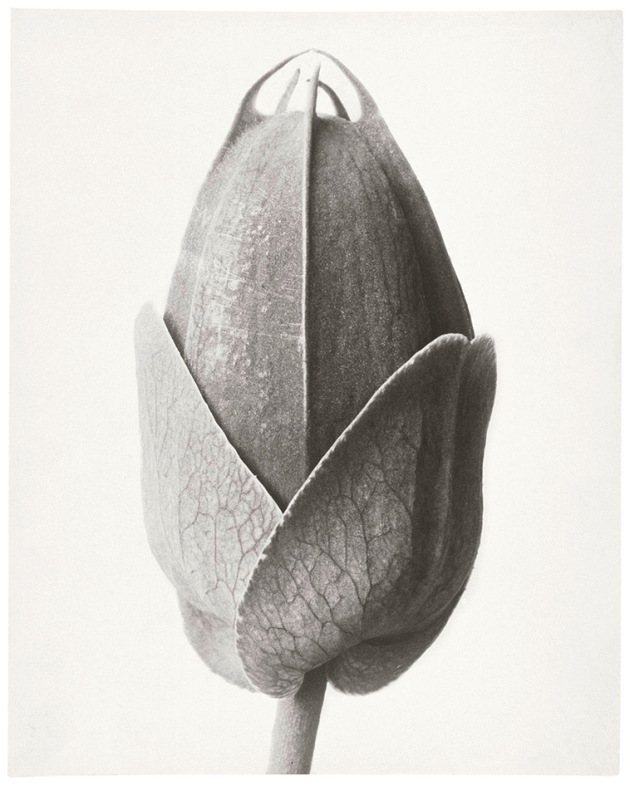

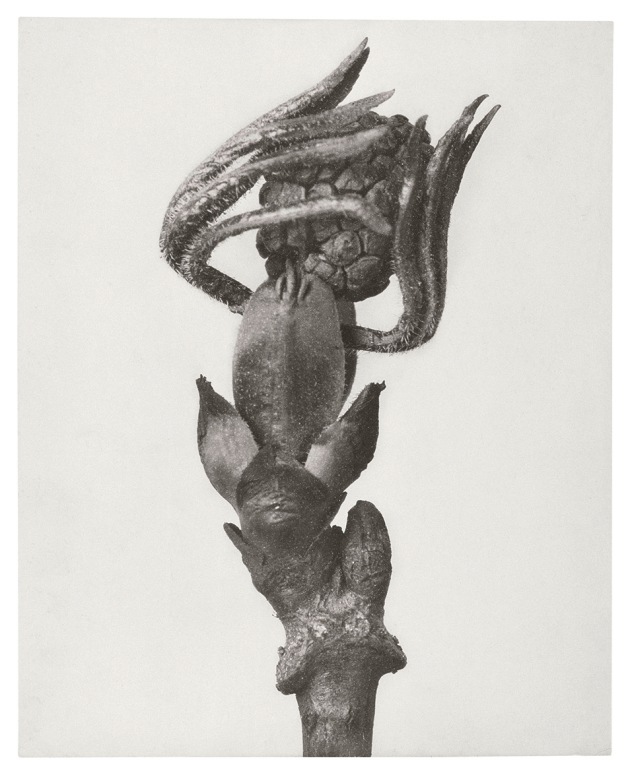

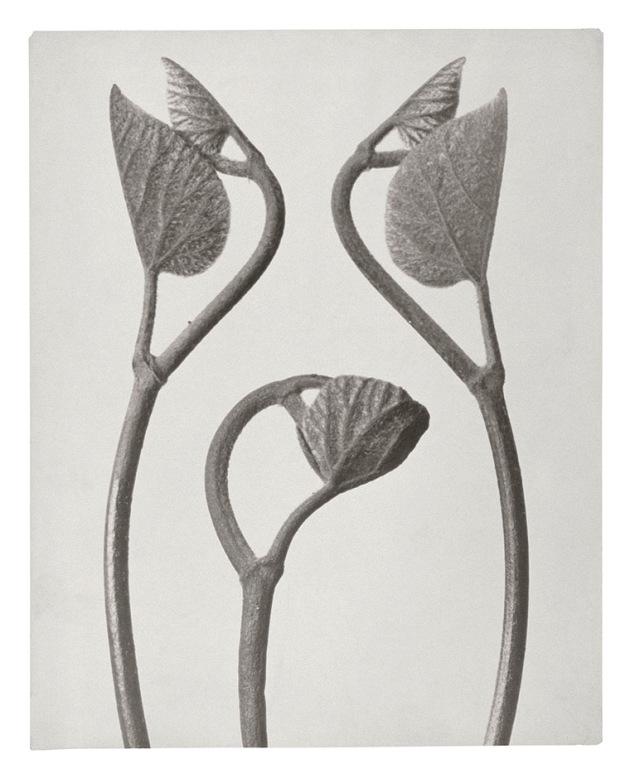

Karl Blossfeldt (1865-1932) who made his photographs at a time when black and white was the only option is described as “a self-taught photographer, Blossfeldt used this newly emerging medium in support of his argument that all forms created by man had their origins in nature. Building a series of cameras with interchangeable lenses, he was able to examine his botanical specimens in unprecedented, microscopic detail revealing their tactile nature, intricate forms and uncanny characteristics.” His technical mastery can not be overlooked and anyone who has tried macro photography will surely appreciate this. Furthermore, Blossfeldt was working at a time when film was not so well developed and the processing of it somewhat experimental; it was not until the mid-nineteenth century with photographers such as Weston and Ansel Adams working with Kodak materials that photography started to approach being an exact science. Yet Blossfeldt also had an artist’s eye, in fact he was a sculptor who made photographs of plants to educate his students, and it was this approach that really made his work stand out. Recognition did not come however until the end of his life.

Tutor Robert Enoch asked us to look at the exhibition and ask questions concerning the way Blossfeldt achieved what he did as well as asking us to consider whether there was an underlying theme to the work; tutor Robert Bloomfield mentioned the cultural context of Blossfeldt’s work in regard to Modernism defined as “A general term used to encompass trends in photography from roughly 1910-1950 when photographers began to produce works with a sharp focus and an emphasis on formal qualities, exploiting, rather than obscuring, the camera as an essentially mechanical and technological tool” and the New Objectivity defined as “a reaction to both Expressionism’s subjective pathos and Abstraction’s rejection of reality, by means of its objective-realistic impetus and the emphasis on a factual approach to the object” with the work taking on the form of a revelation (we see things we would not see ordinarily, the optical unconscious of Walter Benjamin) and being part of the avant-garde of the time.

At the beginning of the exhibition, as I was making notes of what was written on the walls about the work, a member of staff informed me that I did not need to write down what was written because it was in the press release; unfortunately, this did not turn out to be the case and I think the remark was probably prompted by those who wanted to photograph these text panels. This was a reminder of the conflicts that exist between exhibitors,galleries and visitors which in this case spoiled my effort to understand the work and put it in context. I did however manage to get some information after correspondence with the gallery via email who kindly supplied the Blossfeldt images seen here.

There is a 1929 quote from Walter Benjamin that describes Blossfeldt’s work as “an entire, unsuspected horde of analogies and forms in the existence of plants” which comes from a lesser known essay called “News about Flowers”. Another horde was rediscovered in the 1980’s.

One of the first images I look at is a collage of Ferns (Ferns 1 – working collage 14 – made sometime before 1928 and consisting of 22 silver gelatin prints on card), a mosaic of fern photographs, in which the the plants take the form of ornaments rather than merely being reproduced. One might think of the unimaginative photographs of Darwin’s Finches with the dead birds placed simply in a line; Blossfeldt however is creating something with his records. He did not consider himself as creating art (art photography at that time was dominated by pictorialism) yet his background in sculpture obviously gave him the necessary flair. As Blossfeldt wrote in his Art Forms in Nature, “The plant may be described as an architectural structure, shaped and designed ornamentally” and further, “If I give someone a horsetail he will have no difficulty making a photographic enlargement of it – anyone can do that. But to observe it, to notice and discover old forms, is something only few are capable of.”

The Surrealists drew inspiration from his work and George Bataille used Blossfeldt’s photos in his book “The language of flowers”; all this is a reminder of the way a photographer’s work can be re-textualised in unpredictable ways. His work can even be considered alongside the work of Gerard Richter who likewise kept a photographic sketchbook in his Atlas. As Walter Benjamin wrote of Blossfeldt that “he has done his part in that great examination of the perceptive inventory, which will have an unforeseeable effect on our conception of the world.”

Another aspect of Blossfeldt’s work is that he is extracting the plants from their natural environment, placing them in a clinical situation to make reproduction possible. The objects increased sometimes as much as 40 times their life size appear to be something other than they really are; for instance, someone sees bees in one image and yet it is flowers one is looking at. A photograph entitled Water Avens looks like one of them could be a lampshade! One is reminded of how easy it is to project ideas onto images.

Regarding Blossfeldt’s work, one can think of other artists such as Albrecht Durer whose work sometimes featured plants in detail though none as detailed as Blossfeldt. Photography has the ability to see what the human eye cannot! Karl Nierendorf commenting on this work mentions the “fluttering daintiness of a Rococco ornament; the heroic austerity of a Renaissance candelabra; the mystical, tangled arabesques of Gothic flamboyance etc”

Technically, macro photography is faced by a problem of focus and in particular depth of field; it is not easy to show the whole object in detail. Blossfeldt circumvented this by taking his subjects into the studio and isolating them with a plain background. Yet Blossfeldt was not trying to create art through his work rather a reliable record.

One OCA student remarks that the photographs look dated, are a bit ugly and seem to be in a time warp. There is laughter. I can see her point of view because to me Blossfeldt is limited by his equipment and other materials; it may be that his photographs differ so much in contrast and tonalities because he never achieved the control that was to come later when American photographers like Weston and Adams developed their system of exposure and development sometimes referred to as the Zone System Some of Blossfeldt’s prints look rather grubby, the shadows have a tendency to become dense while bright highlight areas do not seem to exist; the differently toned backgrounds might simply be a result of different development times though it may be that he used different coloured backgrounds. One wonders what the comments might be if these images were shown at a local camera club … “what I would suggest mate is use Ilfoduck developer and print on Bogdog paper … gives fantastic results especially if you then tone the print in a pint of Real Ale!’ etc etc

It has been noted that Blossfeldt’s work seems to grow out of darkness; Nierendorf writes that “Just as nature, in the monotony of its eternal growth and decay, is the embodiment of a dark, grandiose secret, so is art an equally incomprehensible organic second creation ...”

The following comment by George Bataille gives some idea of what looking at such work might involve … “the sight of this flower provokes in the mind much more significant reactions, because the flower expresses an obscure vegetal resolution.” Yet how significant are these forms?

After we have seen the exhibition, we make our way to the gallery cafe, get some refreshment and talk amongst ourselves awhile until the tutors start a general discussion.

There is mention of the danger of over-egging work, of reading too much into the images we see. We discuss work by Martin Usborne who has done a series of photographs on dogs in cars, professionally created images in studio-like settings. Is it cruel? The dogs are cared for.

Robert Enoch then asks us all to comment on what makes a Karl Blossfeldt a Karl Blossfeldt !? There is the use of black and white materials (the only choice that Blossfeldt had in his time) and a camera which he made himself. He was a sculptor, a botanist, a recordist – aspects of his persona that come out in his work. He was also a teacher and this presence seems to have come out in the consideration of his work; we are a group of students still learning from his work about a hundred years later.

Karl Blossfeldt’s work is certainly more than just a record, there is something else ticking away. Can his work really be described as “product shots” as someone suggests?

One remarkable feature of the prints on show is that they differ from each other; there seems to be no one way that Karl Blossfeldt uses. This may imply that he lacked professionalism and certainly he lacked the sophisticated materials in use today; however, it is also evidence of his motive, focusing on the uniqueness of every plant’s form so that one starts to notice the difference between them. There is a lot of attention to the frame and one feels that Karl Blossfeldt must have spent a lot of time setting up his photographs since the compositional element is there. He does not have a flippant attitude! As Walter Benjamin wrote in News about Flowers (1929)…”These photographs reveal an entire, unsuspected horde of analogies and forms in the existence of plants. Only the photograph is capable of this. For a bracing enlargement is necessary before these forms can shed the veil that our stolidity throws over them.”

Personally, I feel that one can not overlook the way that these plants have been pulled from their natural environments, extracted so that they fall under the clinical gaze of those who wish to study them. This is perhaps the “punctum” of Barthes operating in a different context to the one intended? Blossfeldt’s plants were dried, they lack the presence of life.

In many of Karl Blossfeldt’s images, there is side-lighting, apparently created by the way he worked in relation to natural light which presumably came from a window; there was no elaborate studio set up. The plants have a certain plasticity, lacking in depth but yielding iconic patterns.

Some images are like buildings such as those of Horsetail. One recalls the leaning tower of Pisa!

Blossfeldt’s images are based on observation. They are not whole images since their framing obscures part of the plant; the view of them is highly selective. Their purpose is the view of the sculptor not the interest of the botanist who might get frustrated at so many images of ferns!

What makes us so interested in natural forms? Their aesthetic appeal perhaps; author Parvati Nair goes further than this in her article on nature photography. We are adversely surrounded by man-made forms and need to absorb nature if only for natural benefit. Nature gives us a bigger picture, it is unpredictable unlike our socialised lives. There is of course the idea, upheld by Blossfeldt, that all man made creations reflect nature in some way but we often fail to see it in the architectural giants that surround us … the Gherkin building in London may be vegetative in composition but when standing on the ground looking up at it, one is unlikely to get this impression.

His work with it’s ornamental emphasis has been linked to the Art Nouveau movement but this view is subjective; Blossfeldt is not considered as being part of that art movement yet is linked to the New Objectivism of which he is considered an unwitting part. Fertility symbolism might be considered as descriptive of his work yet sensuousness is not emphasised, his approach being more manufactured. The black and white emphasises different aspects of the objects such as curves and texture; there is a lack of translucence, a result perhaps of the limitations of the medium at that time. Heraldic is another term that might be applied to Blossfeldt’s work – some of his images remind one of carvings seen in churches.

The German character is in evidence – serious, sober, analytical. One recalls the work of contemporaries to Blossfeldt such as Maholy-Nagy and Renger-Patzch, as well as August Sander whose work is also based largely on straightforward observation; there is the later work by the Bechers who have photographed old industrial buildings such as water towers often with similar flat lighting that helps to bring out detail.

It is an exhaustive discussion and finishes some 3 hours after the start of our visit; many seem inspired and I know I want to explore this kind of work a little more.

My own work around Blossfeldt’s approach can be found in my other blog

Other students have also blogged about this event!

Here is Helen’s account … (she is the third from right in the group photo)

“Great tour yesterday at the Whitechapel Gallery. Thanks so much to Rob Bloomfield and Robert Enoch for their thought-provoking and enthusiastic guidance, and to all the students who participated. It was most enjoyable and I learned a lot. For anyone still unsure about attending one of these events: I cannot recommend it highly enough – it will really bring your studies to life and you’ll meet some lovely people, without being under any pressure to actively contribute.

Here is my write-up for anyone interested:

http://helendigitalfilm.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05/karl-blossfeldt-whitechapel-gallery.html

All comments welcome.”

This one is from Miriam … (includes her own Backgarden Blossfeldts”!)

http://mcpeopleandplace.wordpress.com/2013/05/12/blossfeldt/

Another good one is from OCA student Nigel Robertson …

http://nigelroberson2.blogspot.co.uk/2015/04/assignment-5-blossfeldt.html

As I reread this blog years later, I am working on an image that seems to fit the subject and so include it here …

from a series of “nature” images made in the wild using natural light

Pingback: Review: Karl Blossfeldt | Lucy's OCA Learning Log

You spell Karl Blossfeldt with a K not C.

You are right, I do spell it with a K !

Do you spell it with a C or have you seen a typo in my blog?

Amano

2nd Blossfeldt image from the bottom. Do I win a prize for finding the typo?

what do U want? I sometimes give prints. have posted a photo that I am just about to have printed which kind of relates to Blossfeldt imagery. Thanks for the feedback.

Pingback: Up For A Lark - WeAreOCA

The errant C has now been pointed out to me and altered. Thank You!